There's a long list of things Chris Urmson and his partners at Aurora Innovation refuse to talk about. After months of trying to score an interview with the principals of the driverless-car startup—which has been operating in stealth mode since its launch late in 2016—we're finally sitting down at Aurora's headquarters in Palo Alto, California.

But Urmson, Aurora's Canadian CEO, and chief product officer Sterling Anderson (the third partner, chief technology officer Drew Bagnell, is based out of Aurora's second office in Pittsburgh) won't speak in detail about their technology—it's just too soon, they say. They won't reveal how much financing the company has received—though clearly it's ample, judging from the hiring binge they've been on. To date, they've declared only $3 million (all figures in U.S. currency) in backing, pocket change in a sector in which every major carmaker, plus a handful of tech giants, have already sunk billions. They won't delve deeply into the work they did with their former employers—Google, Tesla and Uber—since they're now technically competing against them (and they've already been sued once, by Tesla).

And they are certainly not prepared to let any outsiders ride in one of Aurora's self-driving vehicles, a small fleet of Audis and other cars kitted out with laser-driven sensors on top—the so-called LiDARs that can cost much more than the cars on which they sit.

Urmson—a big, enthusiastic 41-year-old—is understandably skittish. After all, Aurora is competing in one of the biggest technology races of our time. And he sees more than just a lucrative payday at the end of it. Urmson believes autonomous vehicles, or AVs (an acronym that's bound to become commonplace), will dramatically reduce car-related fatalities and save commuters millions of hours they otherwise would have spent behind the wheel—not to mention revolutionize urban design; public transit; the automotive, insurance and trucking industries; and more.

And this reality isn't far off. The driverless car is already moving from various drawing boards and into the real world. The world's newest car company, Tesla, and the world's oldest one, Daimler, are among those that have pioneered driver-assist programs that go way beyond executing the ever-tricky parallel park. When activated, these systems can take much of a dreary commute or long highway trip off a driver's hands. Tesla's driverless semi-trailer trucks—which can pilot themselves on highways—will go into production in 2019. An Uber pilot program has already put self-steering cabs onto the streets of Pittsburgh and Singapore.

There are risks, of course. The first accidents involving self-driving vehicles—some minor, some mortal—have received widespread coverage. [1] Still, there's a full-on rush to get a piece of the autonomous action. The sums being thrown around are astronomical. General Motors and Ford, for instance, have each recently paid roughly $1 billion to buy relatively small shops specializing in AVs.

There's little doubt the big guys have been watching Aurora's progress. Urmson, after all, is one of the top brains in the AV industry. When he quit his job as head of Google's self-driving car unit in August 2016, it wasn't just big news in Silicon Valley—major publications like The New York Times and The Atlantic speculated about what the robotics wunderkind would do next. His cred, and that of his entire team, has paid off: In January, Aurora announced partnerships with two of the world's largest automakers, Hyundai and Volkswagen.

Urmson might have a few no-go areas when it comes to the details, but he's blunt about what's driving him.

"In 1885, Karl Benz invented the automobile," says Urmson. "On its first drive, it crashed into a wall. For the past 130 years, we've been working around that least reliable part of the car, the driver. We've made cars stronger, added seat belts, airbags, made them smarter. The bug we're working to solve now is the driver. We don't want to patch around the problem, but to solve it."

Aurora occupies a warehouse-style building just off El Camino Real, the old King's Highway that was built by the Spanish and runs much of the length of California. As I pull my old, low-tech Benz into a parking spot on the street behind the premises, one of Aurora's vehicles (the logos have been taken off), with its telltale bucket-shaped LiDAR on top, passes by. Inside the open-concept office are roughly 30 people working in almost absolute quiet. The place is bare bones—there's no massage room, no barista bar, not much art on the walls. Instead of the multi-ethnic cafés Urmson would have been accustomed to while working at Google, there's a kitchenette with some bananas on the counter, along with an old-school coffee maker.

Urmson bounces in, wearing a hoodie and khakis—late, but full of good-natured charm, like Tigger in a Winnie the Pooh body. It seems that whenever he enters a room, he brings laughter with him—today, he cracks up Anderson by debating whether the three partners behind Aurora should be called the Three Amigos or Three Musketeers.

All three of Aurora’s executives are veterans in the self-driving vehicle space—but Urmson is firmly in the driver’s seat

Urmson was born in Richmond, British Columbia, to parents who'd emigrated from England. "They went back for a couple of years but then decided Canada was better," he says. Urmson's father trained as an electrician but, once in Canada, worked to get his high school equivalency diploma, and then a bachelor's degree and a master's. He held a series of jobs in the Canadian prison system, first teaching inmates, then serving as a warden and finally overseeing jails across the Prairies. The family moved often—first to Alberta, then the Yukon, B.C., Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. "I know about winter," says Urmson.

His parents, he says, valued education, always finding houses near the best schools for him and his two younger brothers. Urmson excelled at math and science, and was obsessed with space. One of his first memories was of staying up late to watch a space shuttle flight. "My parents said I should go to bed," he says. "I took that as a non-binding recommendation rather than a command." When it came time to choose what to study at university, he was torn between medicine and engineering, choosing the latter, he says, because he abhors the sight of blood.

He settled on the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. He did well, he says, and finished his degree in 1998. He'd seen a poster in the university's career office, of a robot climbing out of a volcano. "I thought, That's really cool." The poster was an ad for what was then, and probably remains, the world's premier robotics program, at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. The robot was a heat-impervious crawler that climbed into and out of an active volcano in Antarctica. "I didn't think I'd necessarily get into the program, but my girlfriend then—now my wife—Jennifer, said, 'Why not apply?'"

He got in and moved to Pennsylvania (Jennifer would join him two years later). One of Urmson's chief mentors at Carnegie Mellon was a professor named Red Whittaker, a former marine whose robots famously helped clean up the radioactive material spilled at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, a few hours east of Pittsburgh, in 1979. "When Chris arrived, he was this congenial Canadian guy—could not have been nicer," Whittaker remembers. "He said he thought he might like to go back to Canada and eventually get a teaching job. I thought to myself, This is the big leagues here—the hell you're going back and getting a teaching job."

Urmson was part of a team that helped test a robot adept at sensing signs of life in Chile's barren Atacama Desert [2]—the sort of project that was a natural precursor to joining the space program. But the space nut's career took an unexpected detour when Whittaker invited Urmson to join a team building a robot that would attempt to race across the Mojave Desert, from Los Angeles to just south of Las Vegas, in less than 10 hours. The race was sponsored by the U.S. military's research wing, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA. [3] Its goal, says Whittaker, was to get its hands on unmanned vehicles that could move through conflict zones.

Urmson told Whittaker he needed to think about it. It meant extending his studies at Carnegie Mellon, and he and Jennifer were expecting their first child. "But it was this unthinkable mission," Urmson says. "The robot I worked with in Chile moved at 15 centimetres per second, so the prospect of a robot going 50 miles an hour—the speed was appealling."

Over the next four years, Urmson helped lead Carnegie Mellon's teams through three of DARPA's so-called Grand Challenges, which pitted many of the young engineers who would go on to become leaders in the new field of autonomous vehicles against one another.

In preparation for the first race in May 2004 [4], Urmson's team converted a beat-up old Humvee into a machine that could perceive and go around obstacles. Just days before the race was to kick off, the Humvee turned over, trashing many of its expensive top-mounted sensors and hard drives.

When Urmson described watching the crash for a History Channel crew documenting the race, "most of the words I had to say got bleeped out," he says.

Nonetheless, he and his team got their Humvee to the start line of what has been called Robot Woodstock. "All these crazy vehicles were lined up there," Urmson says—cannibalized Jeeps, SUVs, ATVs, and even a self-driving motorcycle.

Chris Metcalf/Flickr

In the end, no one made it through the Mojave course, though Urmson's team went the farthest, about 12 kilometres. In the following year, several teams completed the race, with Stanford's coming in first and Carnegie Mellon's entries coming in second and third. In the third year, the robot cars competed on a mock city course, where they had to navigate intersections and interact with other cars. It was in this so-called Urban Challenge that Urmson came into his own, helping to program the code that made his team's car the winner.

"There's this photo I have of Chris holding his son on the vehicle's hood," Whittaker says. "There's this good, strong feeling in it—this young father, so proud. All of them had to make so many sacrifices, take so much time away."

As it turns out, Google was watching. Around 2009, founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page decided they wanted to do more than Web searches. They launched a semi-secret research and development wing, the X program—also known as the moonshot factory—to find far-out solutions to pressing problems. This is the division that created the short-lived Google Glass and tried providing WiFi to the world via a series of balloons. In 2009, Google hired Urmson, along with several other DARPA race alumni, to build a self-driving car. "When we started, it was kind of a joke," says Urmson, who moved his wife and two sons to Mountain View, California. "On top of everything else, Google's doing self-driving cars."

The program—initially run by Sebastian Thrun, whose Stanford team had won DARPA's second Grand Challenge—set itself the goal of driving more than 100,000 miles on Northern California streets in a year, and pitted its machines against some of what Urmson calls the region's "interesting roads," including San Francisco's curvy Lombard Street and the vertigo-inducing parts of Highway One that hug the coast.

Sightings of Google's driverless vehicles became common in Silicon Valley, with engineers inside, diligently recording their observations. Urmson and his team wrote the code that enabled these vehicles to navigate for themselves.

The team eventually blew through its goals and then some: This past November, the company announced its AVs had logged more than four million miles. Accidents were few and minor, each carefully parsed to figure out what had gone wrong. In addition to adapting commercial vehicles—some Priuses, Lexuses and Chrysler minivans—to the task, Google commissioned its own little prototype vehicle, which Urmson's older son nicknamed the Koala Car because of the little brown, koala-like nose on the front.

"There is some resistance to self-driving cars, some fears about them, and that design was cute," Urmson says. "It was intended to help minimize those fears." [5]

Most existing self-driving systems, including Google's, operate in a two-stage process. They gather information on their surroundings through sensors—laser-driven ones, radar, cameras and sonar—and plug that information into an internal map. Software processes all these inputs to help the vehicle decide what moves to make. The software then sends commands to the vehicle's actuators, which control steering, acceleration and braking. The coding helps it navigate obstacles and follow traffic rules.

A big challenge Urmson and others have worked on is "smart object discrimination": the process by which the car differentiates between a bicycle and a motorcycle or…something else. In a TED Talk about self-driving cars that has since been viewed more than two million times, Urmson showed a graphic of what a Google research car perceived on the road. It was a black screen with various coloured squiggles on it. "This is a woman in an electric wheelchair chasing a duck in circles on the road." The crowd laughed. "There is nowhere in the AV handbook that tells you how to deal with that."

In 2014, around the time Urmson took over from Thrun, the team started to allow Google employees from outside the self-driving division to test out its cars. "One of them was a Porsche driver who said he had no interest," says Urmson. "He came back raving about it. And we watched them using the cars. Although they knew they were supposed to keep focused on the driving, since they could be called on to take over at any moment, you could see, for instance, a test driver with low power on his phone reaching into the back seat, grabbing his bag, taking out his laptop, plugging the phone into it."

As the technology improved, Google began to consider how to roll it out into the world. In September 2015, the company brought in the former CEO of Hyundai, John Krafcik, to oversee the program, which it has since renamed Waymo and spun off as a separate subsidiary of Alphabet, Google's parent. Eleven months after Krafcik's arrival, Urmson announced his decision to leave.

A number of other top engineers left the program around the same time. A couple of theories as to why they left quickly made the rounds—that by giving the people who built the program enormous bonuses, the company had given them incentive to quit; that Urmson and others were impatient with Google, wanting it to release a commercial product sooner rather than later, before it lost its lead.

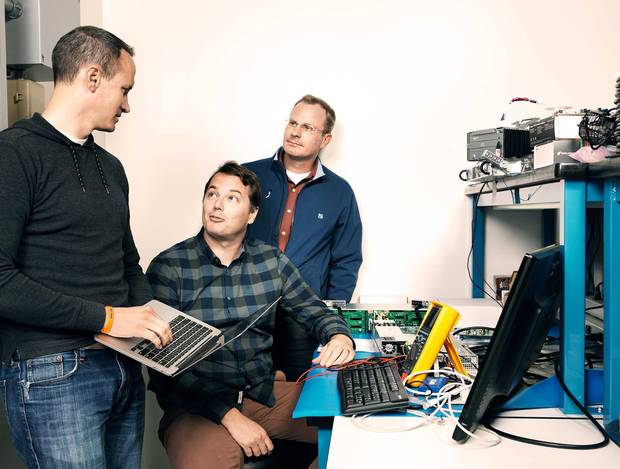

Aurora’s CEO Chris Urmson

Urmson didn't say much at the time, writing a classy piece on Medium that read, in part: "It has been a tremendous privilege and honor to be part of a team that has been at the forefront of bringing this life-saving technology to the world."

In our interview, he will only say: "I just wasn't having as much fun."

As a free agent, Urmson had his pick of jobs. "It was flattering that many people wanted to talk to me, and I realized that the window that was open to me might not be open forever—there were opportunity costs of not doing something."

Nonetheless, Urmson says, "I honestly didn't know what I was going to do. I thought maybe I'd go and sit on a beach for a while."

He didn't, of course—guys like Urmson rarely do. Instead, he got in touch with a couple of fellow AV experts with an eye to launching his own startup.

Urmson had met Drew Bagnell on a grad-student rafting trip when both were doing their doctorates at Carnegie Mellon. "He ended up throwing our captain overboard," says Bagnell, "which I was fine with—he was a better captain." When Urmson came calling, Bagnell had just left Uber, where he had helped get those self-steering taxis onto the streets of Pittsburgh.

As for Sterling Anderson, he'd never met Urmson but knew him by reputation as a strong leader and talented roboticist. He was also a fellow Canuck: Anderson was born in Edmonton to a Canadian mother and American father, and grew up all over the United States. Anderson would regularly visit his mom's family in Canada. "When I was young, my grandfather used to take me out into the Albertan tundra to teach me to limit handle on icy roads in his van," he says. "My earliest lessons on vehicle dynamics came from those lessons with him." Anderson went on to earn his doctorate in robotics at MIT, developing a semi-autonomous safety system to get drivers out of scrapes. After a brief stint at McKinsey, he joined Tesla, where he became head of its Autopilot programs, reporting directly to CEO Elon Musk. [6]

After several meetings with Urmson, Anderson decided to join Aurora. "I think we all felt we wanted to make a difference on a larger scale," he says.

Between the three partners, they've got at least some knowledge of all the major new developments in the automotive world: electric cars, check; ride-sharing, check; self-driving vehicles, check, check, check.

One thing that divides the current competitors in this field is that some, like Tesla, are going for driver-assist programs, a sort of incremental move toward autonomy. Others, including Ford, Google and Aurora, have set full autonomy as their goal—level four or above on an autonomy scale agreed upon by the industry's pioneers.

As for Aurora's plan, it's hoping to build a sort of plug-and-play autonomous-vehicle system. The company is developing specs for the hardware, to be manufactured by a parts supplier or automaker, that will mesh with its software, both of which can be installed on any vehicle platform. "Ultimately, we're wanting to play the role that Microsoft played in the '90s," Anderson explains. "They worked with Intel and the other memory providers on one side of the problem, and with the hardware makers—the IBMs and Compaqs—on the other. And then they licensed the core operating software."

Anderson—by far the slickest of Aurora's three founders and the one who has spent the most time outside the tech bubble—has spent the past 18 months searching for partners. The recently announced deals with automakers will see the company work with Volkswagen on pilot programs to put AVs—"including fully self-driving pods, shuttles or delivery vans, and self-driving trucks without a cabin," according to Urmson—in several cities, notably Hamburg, Germany. Aurora is doing a similar project with Hyundai in China.

As CTO, Bagnell is charged with heading the young company's research and development—though, he says, "in general, it's hard to argue that anyone understands the problem better than Chris." The three try to reach consensus on most issues. "If we don't," Urmson says, "we tend to try to let the person who knows the most make the call."

As for Urmson, Bagnell says simply: "He's the boss." The boss has had plenty of distractions, however. First off, he played a small role in a lawsuit Google brought against a former colleague and sometimes rival, Anthony Levandowski. Another veteran of the DARPA Grand Challenge, Levandowski joined Google's self-driving program early and reportedly got a $120-million bonus shortly before leaving to found the AV startup Otto, which Uber recently acquired for $670 million. [7] In the suit, Google contends that Levandowski took 50,000 work emails with him when he quit, some of which contained trade secrets, and poached a number of Google's best employees, in breach of his commitments to the company.

Aurora’s driverless cars have some serious electronic gear in the trunk. But where will your suitcases go?

As someone with a close-up view of some parts of this conflict, Urmson has been deposed in connection with the case. In sworn testimony, he revealed a tougher side to his personality: "Over time, my patience with his manipulations and lack of enthusiasm and commitment to the project—it became clearer and clearer that this was a lost cause." When he learned Levandowski was approaching members of the self-driving team to defect to Uber, Urmson wrote an email to colleagues, disclosed in the suit, that stated: "We need to fire Anthony."

Aurora has faced its own legal woes over poaching. In January 2017, Tesla sued Aurora, and Anderson and Urmson personally, alleging that the pair were poaching talent as Anderson was heading out the door, and that Anderson had also taken trade secrets with him. "Not true," says Anderson. He calls the lawsuit "meritless" and says his former boss, Elon Musk, had engaged in "deception" in launching the lawsuit. This past spring, Tesla dropped the suit after Aurora agreed to pay $100,000 for an independent audit to confirm none of Tesla's intellectual property had come with Anderson.

"Tesla has withdrawn its claims, without damages, and without attorneys' fees, without any finding of wrongdoing," Anderson wrote at the time of the settlement. "In spite of this distraction, we've made great progress."

Urmson is the first to admit there's a lot of hype—"bluster" is his preferred term—in the self-driving sphere. It's an increasingly crowded sector, one that faces many challenges, some technical, some financial, some social.

In the attempt to commercialize the emerging technology, Aurora, like all the other early entrants in this field, are coming up against one hard obstacle: the price of sensors. Those LiDARs currently cost upwards of $70,000, more than most commercially available cars. So as not to price their cars out of the market, Tesla has opted, at this point, not to use the expensive laser sensors for their current driver-assist programs. (It's expected that prices will drop as demand rises.)

Anderson believes (as do many other industry watchers) that the first commercial AV application will likely be fleets of self-driving vehicles for transit companies—trucks that do the most soluble sort of driving, which is highway driving, and self-driving taxis that move slowly around our cities. (Aurora's new partnerships aim to produce vehicles of the latter sort.) In this setting, the purchase cost gets offset by an AV owner's ability to use the vehicles around the clock.

Sam Abuelsamid, an automotive expert and senior analyst at Detroit-based Navigant Research, says the new industry will likely have certain consequences for the auto parts sector, a major driver of the Canadian economy. "The cars will still need certain things—tires, brakes—but with this greater usage, they'll wear out in less time. Same number of miles, but less time. And, of course, the electronic parts makers—that's going to change dramatically."

And there are even more difficult questions AV companies will have to grapple with. Who will be liable if, or when, these self-driving vehicles get into crashes? Will it be the car manufacturer, the vehicle owner (who is not, in the case of full autonomy, even driving the vehicle), the producer of the self-driving system within, or all of the above?

Urmson says the probable displacement of truck drivers and delivery people is something that keeps him up at night. More Canadian men identify as truck drivers than as any other type of worker. [8] There would, of course, be some new jobs coming out of this sphere, but the skills needed would differ.

Then there's the weather factor: Has any self-driving car shown it can deal with one of the world's great driving challenges—the winter? "Much of the testing to date has been in places with mild climates, without a lot of rain," Anderson says, mentioning the tests being done by several companies in Phoenix. "So, no, the winter is still something to figure out."

Yet, for all these challenges, Urmson, in particular, remains confident the pros will outweigh the cons. In that 2015 TED Talk, Urmson told the audience that, according to the most recent statistics, 1.2 million people die in traffic accidents worldwide each year, 33,000 in America alone. "That's a 737 falling out of the sky every working day," he said. [9] He then spoke of the growth in traffic. "From 1990 to 2010, the number of vehicle miles travelled grew by 38%, while the roads grew by 6%. There are six billion minutes wasted every day—that's 162 lifetimes." AVs, he believes, will largely solve these problems, as well as bring mobility to those who might not otherwise have it: In his TED Talk, he showed a video of a blind man riding in a prototype AV through Austin, Texas.

They're facing an uphill battle, according to Abuelsamid, who recently authored a Navigant report on who's leading—and who's trailing—in this new field. He says the proliferation of decent, if not-yet-quite-there, software solutions means the carmakers have greater leverage than the tech companies at present—accordingly, he placed Ford and GM at the top of the leaderboard in his 2017 report. "There are now so many companies in this space, the software is becoming a commodity," he says. "On the other hand, car companies have so many things the tech companies don't—dealer networks, the ability to turn out a relatively safe vehicle at scale."

Still, Abuelsamid believes Aurora has a shot. "They will likely be in next year's report," he says, "as one of those to watch, in the new 'Up and Coming' section. This is based on who is running it. But unless we have more information, it's hard to place them. We're a long way from the finish line in this race. I think, really, we're just approaching the starting line. But for startups like Aurora, it's critical at this stage that they find the right partners."

Now that Aurora has joined forces with Volkswagen and Hyundai, they're much closer to hitting the streets. Which is a good thing, because for Urmson, time is running short.

"I've always said one of my main goals in working on self-driving cars is to ensure my older son never gets on the road," he deadpans. "He's 14 now. So we've gotta make it happen."

[1] In May 2016, a Tesla driver was killed after apparently ignoring the car's warnings that he needed to take the wheel. Last November, a truck driver ran into a self-driving bus in Las Vegas. In May 2016, a Tesla driver was killed after apparently ignoring the car's warnings that he needed to take the wheel. Last November, a truck driver ran into a self-driving bus in Las Vegas.

[2] It's the driest non-polar desert on Earth, with Mars-like soil

[3] DARPA helped birth GPS, stealth aircraft and the early Internet5]

[4] First prize: $1 million

[5] 56%: Americans who said they wouldn't want to ride in a driverless vehicle, citing mistrust of the technology, lack of control and safety concerns as the top reasons (according to a 2017 Pew survey)

[6] "It's too dangerous. You can't have a person driving a two-ton death machine." —Elon Musk in 2015, predicting manual driving would one day be outlawed

[7] The otto sale, plus GM's $1-billion deal for startup cruise, prompted one observer to peg the going rate for self-driving-car experts at $10 million a head.

[8] Canada: 227,000 truck drivers | U.S.: 3.5 million truck drivers

[9] Zero: Number of passenger jet crashes in 2017, the safest year in aviation history