The past can be irritating. This is especially true if you’re touring a country with such a plenitude of past that it borders on surfeit. In the late 19th century, Henry James famously decried America’s lack of castles, ivied ruins, pictures and museums – civilization, in short. But what contemporary tourist in Italy, say, or France hasn’t thought at the end of a long day’s journey into history, “One more Madonna and Child and I’m officially an atheist”?

Every now and then, however, the past becomes present, a palpable thing, and not some musty near-abstraction or inert souvenir from a distant, long-vanished culture. I had this sensation one cool, overcast afternoon in northern Greece last month as I descended the 20 or so steps leading to the entrance to the tomb of Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great.

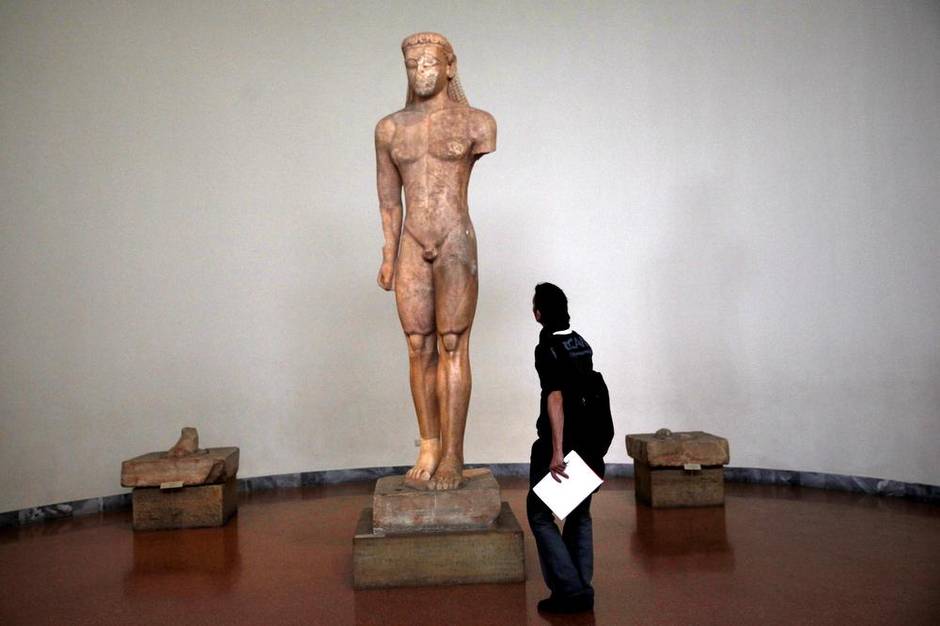

Maybe it was the drama of the setting that got to me. The tomb, one of three excavated by archaeologists in the 1970s, is housed under a grass-covered mound near the village of Vergina (formerly known as Aigai, ancient capital of the Macedonian kings) into which the Greek government inserted a magnificent museum in the mid-1990s. Perhaps, too, it was the narration of the museum’s archaeologist, Yiannis Grekos, as he walked the 1,000-square-metre interior, its vitrines filled with treasures. The sepulchral calm, the chiaroscuro of the space – you felt like a character in a hologram of a Caravaggio painting.

Or maybe it was knowing that the entrance to Philip’s tomb is, save for time’s wear and tear, just as it was in 336 BC when Alexander, then 20, interred his murdered father’s cremated remains and those of Meda, youngest of the 46-year-old Philip’s seven wives, behind its doors. The entrance has never been opened since the doors were closed nearly 2,400 years ago. Fearful that the facade, with its famous frieze of Alexander hunting with his father, would collapse, excavators entered the tomb through its roof to discover its contents, among them two marble sarcophagi, one with a 24-carat gold chest enclosing Philip’s ashes and the king’s feathery crown of golden oak leaves and acorns.

Then again, perhaps that sense of all time being eternally present had to do with … shopping. Grekos went to a display case and pointed to an exquisite gold medallion, fashioned in the face of a snake-haired Gorgon, originally attached to Philip’s leather-and-linen breastplate. Stare into her eyes, legend has it, and turn to stone. “Does it look familiar?” Grekos wondered aloud, genially challenging a touring group of journalists, museum officials and documentary filmmakers. A few seconds passed and then … eureka. Looming through the mists of Greek mythology was something close, very close, to the corporate logo Gianni Versace chose in 1978 AD as the lust-inducing face of his fashion empire.

Canadians can make the connection themselves at Montreal’s Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Museum of Archaeology and History. The gold Gorgon, one of 65 artifacts on loan from the Museum of the Royal Tombs, is on display there through April 26, 2015, as part of The Greeks: Agamemnon to Alexander the Great. (After its Montreal berth, the show travels to the Canadian Museum of History [CMH] in Gatineau for a run starting in June, followed by showcases in Chicago and Washington that extend into 2016.) With a total of more than 520 antiquities, including ensembles, lent by 21 museums from across Greece, the busts, vases, jewellery, coins, weapons, sculptures and, well, bling represent what Robert Peck, Canada’s ambassador to Greece, calls “the largest exhibition of Greek treasures ever presented in North America” and “the most important exhibition Greece has ever sent abroad.” Indeed, the largesse far exceeds what Greece lent the Louvre in 2011 for an acclaimed Alexander/Macedonia show that drew almost 300,000 visitors during an 80-day run. Unsurprisingly, negotiations and planning for the Canada/U.S. tour took more than two years, with the CMH leading the consortium of four museums.

That the loans are of the highest quality is exemplified by the Athens-based National Archaeological Museum’s decision to include among its 150 offerings one of its most fabled and valuable antiquities: the gold funerary mask of Agamemnon. Sometimes called the “fat man mask,” it was excavated in 1876 by German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann at the palace of Mycenae, 120 kilometres south-west of Athens. It was this mask, from a grave dating to the 16th century BC, that prompted Schliemann to famously declare, “I have gazed upon the eyes of Agamemnon.” (Agamemnon being, as the Iliad has it, the monarch who united Greece’s city-states in the 10-year war against Troy.) The mask’s inclusion marks the first time it’s ever left Greece (it’s estimated 300 of the exhibition’s other artifacts also have never left the country). By some estimates the mask is worth more than $250-million.

Moving beyond the beaches

Why, you may ask, is Greece, a nation historically loath to lend its antiquities and extremely cautious when it does, sending so many artifacts abroad for such a long time? A drive through the countryside provides part of the answer. The depopulated towns with their abandoned businesses and homes are evidence that Greece continues to suffer from what Greeks call the kriss – the crisis. Unemployment hovers around 26 per cent; youth unemployment, according to several politicians I spoke to, is at 60 per cent. The trade deficit in September was almost €210-million ($300-million), and per capita income is around $18,000 (U.S.).

Nevertheless, there are some positive signs – and the country’s coalition government is keen to nurture these further through initiatives such as Agamemnon to Alexander. The number of tourists, for example, is expected to surpass 20 million by year’s end, a record according to Tourism Minister Olga Kefalogianni. Canadians, 250,000 of whom visited Greece last year, are especially welcome, spending about €1,500 each, the most of any nationality. Kefalogianni and Culture Minister Konstantinos Tasoulas are keen to expand tourism beyond both its May-to-October high season and the Aegean Islands, where visitors tend to speed upon arriving in Athens. Why not ski the slopes of Mount Vermio or Mount Kaimaktsalan in northern Greece in February? Why not tour the superbly curated New Archaeological Museum of Pella and environs in November?

At the same time, the exhibition is not just a tourist appetizer (“You’ve seen the best of Greece; now see … Greece!”). It’s part of a major diplomatic initiative, too. The Greeks are eager, desperate even, to see the return of the Elgin Marbles – or as they prefer, the Parthenon Marbles – which have been displayed at the British Museum in London for close to two centuries. Removed from Athens when Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire, the 2,400-year-old marbles are seen by most Greeks as an egregious example of imperialist pillage, a wound only repatriation can salve.

The Greeks even have a place ready for their return, a magnificent neo-Brutalist museum at the foot of the Acropolis, completed five years ago. Head to the museum’s third floor and you’ll find the roughly 50 metres of original marble frieze Greece owns, supplemented by plaster copies it made of the 80 metres in the British Museum. Foreign Minister Evangelos Venizelos told our group the Agamemnon to Alexander tour could be the start of a “perpetual loan” of many antiquities beyond Greece’s borders – if, that is, the world backs Greece’s repatriation claim.

Time past becomes time present

Agamemnon to Alexander promises to be a stellar happening, with Pointe-à-Callière and the CMH each expecting between 150,000 and 200,000 visitors. That there ain’t nothin’ like the real thing, though, was made palpable the sunny, summer-like afternoon we travelled to the palace of Agamemnon, about 120 kilometres southeast of Athens. Returning to our chartered bus, we were told our next stop would be Nafplio, a lovely resort town on the Argolic Gulf and home to (uh-huh!) yet another archaeological museum lending antiquities to the exhibition.

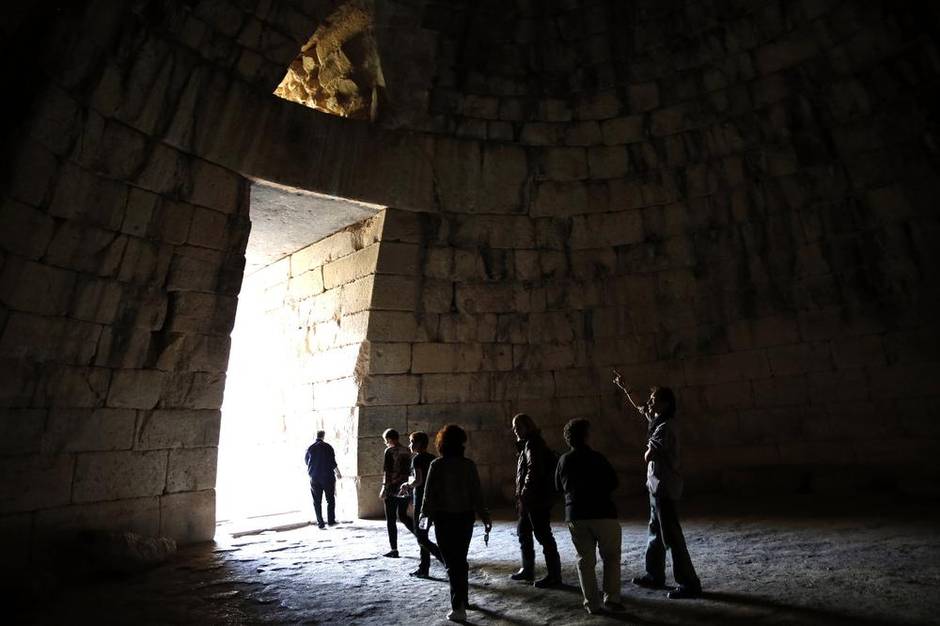

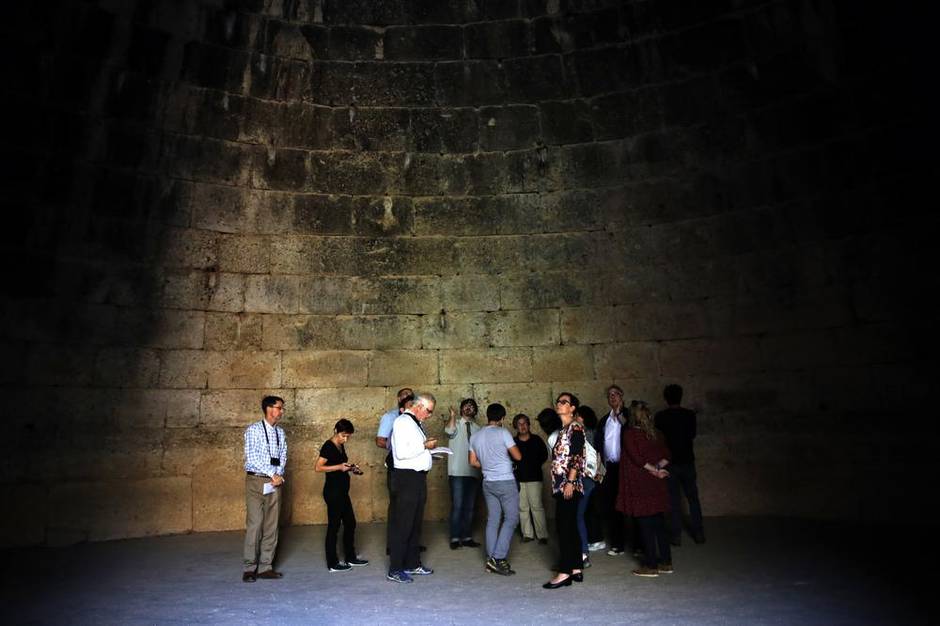

About a kilometre or so into our journey, however, the bus abruptly pulled off the road to park by a security shed. We just had time, it was announced, for a brief visit to something called the Tomb of Agamemnon. Truthfully, I wasn’t expecting much; yes, the palace experience had been impressive, but I was jet-lagged and daunted by the fact that an evening flight to Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest city, lay ahead. However, as I approached the inclined entrance to the tomb, all weariness and wariness ebbed. Okay, the tomb, built around 1250 BC, probably didn’t house the remains of Agamemnon who, as CMH archaeologist/exhibition lead curator Terence Clark had reminded us at Mycenae, was as much figure of Homeric myth as verifiable history. Nevertheless, it was clear from the seven-metre height of the portal, the eight-metre width of its lintel and the huge beehive of its semi-subterranean interior that one Very Important Mycenaean Person had been laid to rest here. As would happen a couple of days later at Vergina, time past nestled with time present and, awe-struck, I gloried in the glory that was Greece.

THE MUST-SEE MUSEUMS

Antiquities museums? Greece has more than a few. The most famous are, of course, the National Archaeological Museum and the Acropolis Museum, both in Athens and each worth a lengthy visit. Among others of interest:

New Archaeological Museum of Pella. This airy, uncluttered, thoroughly contemporary space feels as much like an art gallery as antiquities showcase. It includes the famous pebble mosaic of Alexander the Great hunting a lion with nobleman Craterus.

Numismatic Museum of Athens. This museum is lending 30 ancient coins to The Greeks tour. Even if coins are not to your taste, the venue’s worth a visit as its three storeys, built in 1880, were once the mansion/home of Heinrich Schliemann, excavator of Troy and Mycenae. The lovely grounds are an oasis from the bustle of downtown Athens.

Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki. In the 16th and early 17th century Jews were the vibrant majority population of Greece’s second largest city. At the start of the Second World War, they numbered 50,000 and attended 30 synagogues. By war’s end, Auschwitz had claimed most of those; today the city of one million is home to just 1,000 Jews. This fascinating museum presents the full, sobering history.

Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. This a masterpiece of Greek modernist architecture is home to the famous Derveni krater, fashioned from bronze and tin circa 330 BC; its huge, elaborate surface, depicting the wedding of Dionysus and Ariadne, is often touted as the progenitor of the baroque.

Archaeological Museum of Nafplion. This is a small museum, situated about 25 kilometres south of the famous Mycenae site, but one packing considerable visual punch. It features Europe’s oldest suit of armour, it’s made of bronze, dated to 15th century BC and topped by a helmet made of boars’ tusks.

IF YOU GO

The Greeks: Agamemnon to Alexander the Great features more than 500 artifacts and spans more than 5,000 years of history. It is on now at Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Museum of Archaeology and History, until April 26, 2015. Adult admission is $20 and includes all museum exhibits. pacmusee.qc.ca

The exhibition will make three other stops:

The Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, June 5, 2015 until Oct. 12, 2015; historymuseum.ca

The Field Museum in Chicago, Nov. 26, 2015 until April 17, 2016; fieldmuseum.org

The National Geographic Museum, Washington, May 26, 2016 until Oct. 9, 2016; events.nationalgeographic.com/national-geographic-museum

Costs of the author’s trip were covered by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports in association with the Canadian Museum of History. Neither reviewed or approved his story.