I don't remember when I learned that there once was a place called Africville in Nova Scotia, and that it had been a neighbourhood of black people who had their homes destroyed by the government. Whenever it was, it was an incomplete lesson, since I came away imagining that this travesty had happened a quote-unquote long time ago, in an age before cars, maybe even the telephone.

So it was disorienting when, a few weeks ago, I saw photographs of the former residents of Africville in a tiny museum on the Bedford Basin in the northeast corner of Halifax. These were colour photos, of people watching colour televisions, in houses that look exactly like many of the houses that people still inhabit in the city just up the road.

The neighbourhood of Africville was torn down in the mid-1960s, with the last resident leaving just 10 years before I was born. People who lived there are still alive: There's a 72-year-old named Eddie Carvery who hangs out in a trailer outside the museum every day, unwilling to leave without reparations.

Former Africville residents have been protesting continually since the neighbourhood was torn down in the 1960s.

Steve Jenkinson

This isn't what Canada used to be like, back then. This is Canada, right now.

If there was anyone who expected the 150th anniversary of Confederation to unfold as a fun party accessorized by a huge inflatable duck, the past six months must have been an unwelcome surprise. Instead, the year has brought a nationwide airing of lost or suppressed stories and the chance to catch up with centuries of Indigenous resistance.

It has also brought reconsiderations of formerly lionized figures, including Edward Cornwallis, the British military officer who settled Halifax, whose name is on streets and parks all over Nova Scotia, and who encouraged the genocide of the Mi'kmaq who already inhabited the place he wanted to found.

A call to remove his statue from a city park has been met with resistance: There are those who dislike the complicating, rather than celebrating, of Canadian history.

I, for one, am here for it.

While in my school days Canada was depicted as a place that the French and English created from scratch before inviting the rest of us to submit job applications, it's obvious now that there's more to the story. And since reading Lawrence Hill's 2007 epic novel The Book of Negroes, about a West African woman enslaved in the United States before moving to Nova Scotia as a Black Loyalist, I've been curious about the pre-Confederation African-Canadian community at the country's eastern tip.

So I set out to spend a long weekend learning history and eating seafood, the latter hopefully in a restaurant or bar owned by black Nova Scotians with whom I could chat about modern life. It turned out to be an eye-opening and occasionally frustrating exploration, one that emphasized how unpleasant bits of Canada's past are still hidden, or at least obscured.

Black Loyalists escaping the United States first landed in Shelburne, Nova Scotia.

Steve Jenkinson

Some of the province's important black-history sites are, thankfully, easily found, especially in Halifax proper. That includes the Africville Museum, which is housed in a replica of the tiny Seaview Baptist Church, the central community gathering spot before it was torn down in the dark of night in 1967.

Inside, there are panels that explain that the community dates back to at least 1848. Residents farmed, fished and lived simply but happily, and, by 1917, there were about 400 people on hundreds of acres of land. Though they paid municipal taxes, they never received plumbing or other services, and the city steadily surrounded its black neighbourhood with all the things other neighbourhoods rejected, including an abattoir, an open-pit dump and an infectious-disease hospital. In 1947, Africville was designated industrial land and talk of eviction began.

If you're lucky, the staff member on duty will be Jaden Dixon, who has a family connection: one of the church's eight founding families was hers. "In Grade 9 social studies, we were looking at photos and I said 'that's my dad,'" the 20-year-old said. "My teacher didn't believe me at all."

Her father, Terry, spoke to her class about his time in the neighbourhood, where he lived until he was 12. He mostly chose to share positive stories, but Dixon knows the whole saga: "They moved them out in city garbage trucks" she said, a gross bit of humiliation that plays out in old black-and-white news clips on one of the touchscreens that dot the space.

"To this day, the isolation continues. There's no bus that comes down here," she says. My taxi driver had already mentioned that only one other customer has asked to be dropped off here in the five years since the museum opened.

More centrally downtown is the Camp Hill Cemetery, where Viola Desmond lies beneath a flat, simple headstone. Desmond, who will be on the $10 bill next year, was arrested for sitting in the white section of a segregated movie theatre in 1946 and not pardoned until decades after her 1965 death.

Her grave is found near the centre of the cemetery, likely because of her status as a successful business owner: At the time, many black people were relegated to burial plots on its outer edges. There isn't a clear indicator of where the "coloured" graves are at Camp Hill, but historians say about 200 bodies were segregated in the cemetery's corners.

The Camp Hill cemetery, where civil rights hero Viola Desmond is buried.

Denise Balkissoon

I wanted my trip to be about the present as well as the past, and had tried researching black-owned stores, restaurants and bars to visit before I landed. The only place I had been able to find was the Kwacha House Cafe, owned by Folami Jones, daughter of the late lawyer Burnley (Rocky) Jones, who co-founded the 1960s activist group Black United Front and invited the Black Panthers to Halifax.

When I got to Kwacha one afternoon, the door was locked and the place had a look of permanent disuse. I tracked Jones down on the phone to ask what was going on.

"I'm not surprised you didn't find any other black-owned spaces, because there aren't any," she said resignedly, confirming that Kwacha is on the verge of closing. It's too far outside of downtown to attract regular clients, she said, and rent in a busier location is much more expensive.

That includes in Halifax's historically black north end, where many families moved after Africville was bulldozed. Like elsewhere in Canada, poor and working-class residents are being pushed out by gentrification. "The buildings there are no longer black-owned," Jones said of the streets scattered with new restaurants and quirky shops.

Lion and Bright on Agricola Street is run by a father and son who are more recent immigrants from South Africa. On my visit, the gin sour spiked with black-pepper syrup was delicious and the crowd was almost entirely white, but Jones said that occasionally, a local DJ who "grew up on the old sound" plays tunes that attract Halifax's original black community.

Beyond that, church and barbershops, there is nowhere public for black people to gather – at the Africville Museum, Dixon said an annual barbecue held by the musuem's genealogy society was the only black event she could count on. "It's what we're yearning for," Jones said.

I had to decide which way to go out of the city, since it wasn't possible to visit every site of interest in a couple of days. The east offered the Black Cultural Centre, which promised art and music, and the Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, which offers a tour outlining the area's history of enslavement. But in the end I went west, to Birchtown.

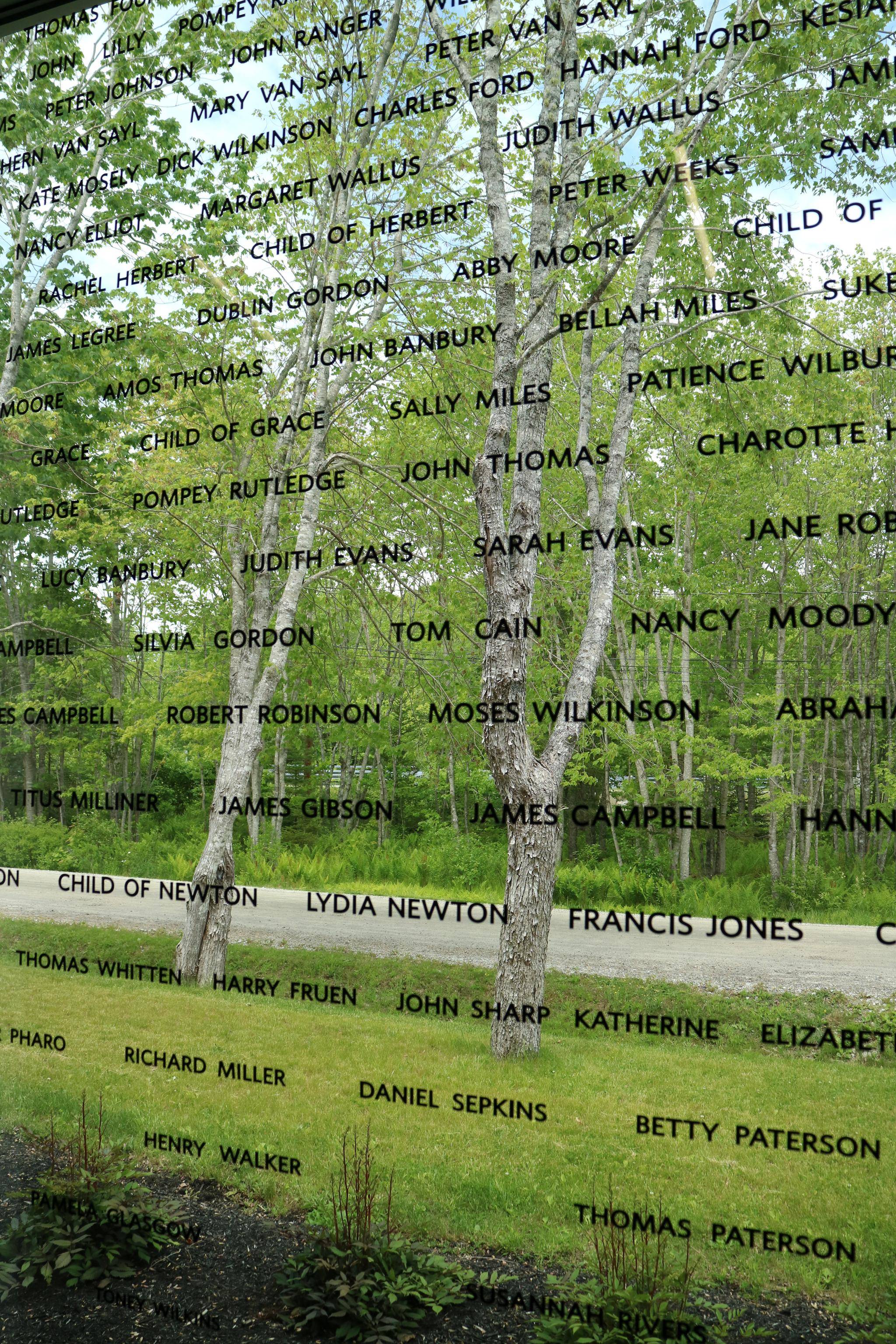

My destination was the new Black Loyalist Heritage Centre, a peaceful 2 1/2-hour drive away. It's built where the first free black settlers lived, which, by the late 1700s, was the largest settlement of free black people outside of Africa.

The descendants of Black Loyalists raised $4-million to build this museum after their original office was set on fire.

Steve Jenkinson

Again, multimedia touchscreens serve up history in digestible chunks. Yes, the enslaved aided Britain in its war against the Americans, but "Black Loyalists" were likely more dedicated to the idea of freedom than the Crown. White Loyalists were permitted to bring all of their property – including people – with them to Canada: In 1784, there were 2,700 black people here, and only about 60 per cent of them were free. A pair of manacles once used on human beings is rusty, disturbing proof.

The hard work of building a new life was exacerbated by racism: Many merchants paid black labourers less than white ones, stoking resentment, while others signed former slaves onto multiyear "indentureships" that didn't look much different than their previous lives. Black homes were destroyed and "negro frolics" (or dances) banned and, in 1792, more than 1,100 early black settlers gave up on Nova Scotia and set off for Sierra Leone.

This story is global, and always has been: Jamaican Maroons were also exiled in Nova Scotia in an attempt to suppress their uprisings in the Caribbean. It's also as knotty as the rest of Canadian history: Black settlers were given land that was inferior to that assigned to their white counterparts, and all of it was unceded by the Mi'kmaq.

The site has always been revered by the descendants of Black Loyalists, as well as the the target of racist attacks. In 2006, when it was just a simple bungalow, irreplaceable photographs, genealogical records and other documents were destroyed in a fire – a man was later charged with arson, though the charges were stayed. The need for a new and better space to share and save this history kicked off a fundraising drive.

The eventual $4-million build fund included money from every level of government, and the results are worth it: The centre is informative, well-designed and accessible to both children and adults. If only as much could be said for the Mathieu da Costa African Heritage Trail, along the northern coast of the Annapolis Valley, which I tried to visit next.

This one-room 1830s schoolhouse is part of the Black Loyalist Heritage Centre.

STEVE JENKINSON

Da Costa was the first recorded free black person to land in what's now called Canada, a multilingual explorer who came to Nova Scotia around 1603 and translated between French colonizers and Mi'kmaq inhabitants. An historical website promotes a trail spotted with "panels" commemorating him and other notable people and events but lacks a map: I was told one could be sent via actual mail, but I was already in town.

I set out attempting to use online maps and more or less failed. My first setback was a pelting rainstorm that made it impossible to drive to remote Digby, the site of da Costa's landing.

All didn't seem lost initially, since the site pointed out a few spots closer to the city, in the eastern part of the valley. But the day dissolved into mucky walks around various buildings and fields that didn't indicate why I should be there – either I made my way to the wrong address three times, or the panels didn't exist.

Equally sodden was the land behind the Emmanuel Baptist Church in Upper Hammonds Plains, where a cemetery of black refugees of the War of 1812 was discovered just last year. Eventually, I gave up and visited a few wineries, with a sense of anxiety at having failed.

Travel is about exploration without expectations, and disappointments are always as likely as delights. The grassroots nature of the province's successful black-history sites, including the Loyalist centre and Africville Museum, are testaments to a community's enduring entrepreneurship and self-love: informative and real and a pleasure to explore.

But the neglect of others indicates that, a century and a half into Canada, the value of certain histories are still up for debate, as is how they contribute to a lack that echoes today. Black people have been in Nova Scotia since before this place was given that name. They deserve to see themselves in the country's official story, if for no other reason than the simple truth.

And many visitors would appreciate a chance to interact honestly with those truths and experience a place the way it really is. I learned the history and I ate the seafood, but I'm still figuring out how all the pieces fit together.