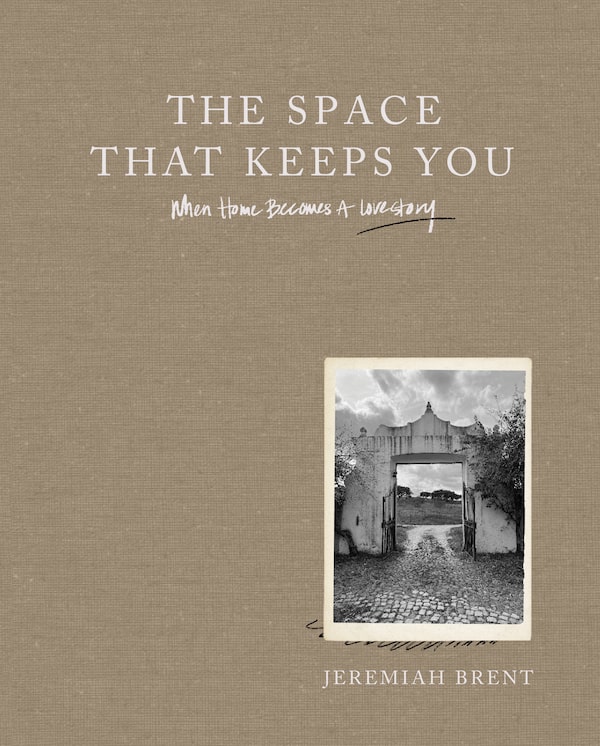

Jeremiah Brent’s new book, called The Space That Keeps You: When Home Becomes a Love Story, was released last month.Paolo Abate/Supplied

American interior designer Jeremiah Brent got the idea for his new book when he was sitting in Oprah Winfrey’s dining room in Montecito, Calif.

The two friends were chatting about what the word “home” means and why some people (like Winfrey) fall in love instantly with a place and stay. And why others (like Brent) move around constantly, forever looking for a place they feel a special connection to. Brent was lamenting that he and his husband, fellow interior designer and TV personality Nate Berkus, had moved 10 times in 10 years. He was worried there was something wrong with them.

Winfrey assured him they were fine, but suggested rather than pay a therapist to find out why they struggled to put down roots, perhaps he could write a book that explored the essence of home – a notion that has consumed him since his youth because he and his single mom, Gwen (who held down three jobs to make ends meet), moved around a lot.

And so, Brent left Montecito and started calling publishers. His pitch went something like this: “I told them it’s a design book, but it has nothing to do with design. I also told them that I didn’t want this to be a book about fancy rich people, and their fancy homes. I wanted it to be an emotional design book, not a pretty design book.”

“Their reaction,” he adds, in a phone interview from his Manhattan apartment, “was a mixture of confusion and panic.”

Paolo Abate/Supplied

Brent’s new book, called The Space That Keeps You: When Home Becomes a Love Story, was released last month and it is the exactly the “design book, but not a design book” he dreamed of. It begins and ends with a personal retelling of how he and Berkus, who have two young children, Poppy and Oskar, eventually found not one, but two homes (one on Fifth Avenue, and the other, a fixer-upper in Portugal) he thinks are their “forever places.”

In between the opening and closing chapters, he tells the stories of nine individuals and families – many of whom he’s known for years – who all have relationships to their homes that he describes as “rich with life and story.”

There is Winfrey, who loves her Montecito home so much she christened it “the Promised Land”; children who are taking care of their deceased parents’ legacy in art and architecture in their house in Mexico; a family that runs the first Black-owned winery in Napa on a homestead that was their parents’ happy place; a gallerist who abruptly left New York to live on a farm in the Portuguese countryside; a chef and grandmother in the Italian town of Giarre, who would never dream of leaving the tiny apartment she and her husband have lived in for 40 years because she loves the light; and a dancer who left the Los Angeles home where she raised her son, and moved to Ojai, Calif., where another special property helped her to cultivate a new piece of herself.

All of these people share one common belief: If a property is really for you, you know in the first five minutes. Before writing the book, Brent wasn’t sure that was true. He is now a convert. He and Berkus put an offer on the Portugal property – which was in “ruins” – on the first day they saw it.

“When I imagined The Space That Keeps You, I was curious about what motivates people who stay, who return, who put down roots and spend their lives tending to the vines,” says Brent, co-host of HGTV’s The Nate & Jeremiah Home Project. “What captivated me is not how structures look, but the energy they contain. I’m obsessed with things like that. I’m fascinated by the kind of people whose grandchildren visit the home that they raised their children in.”

“Connecting with these people and hearing their stories, helped me to figure out what it is about a house that holds you,” adds Brent, who has concluded it is the people, the memories and the love shared within its walls.

Brent’s fascination with homes began when he was a child growing up in Modesto, Calif. On weekends, he and his mother would go on home tours, “checking out the open houses for homes we could not afford.” After high school, he moved to Los Angeles. His introduction to design as a career, he adds, was purely accidental.

At 18, he was trying to figure out what to do with his life, and to keep himself busy he would find second-hand pieces of furniture at Goodwill or on the side of the street and remake them for himself. Then friends (like the dancer, Fatima, featured in the book) would ask him to make something for them. He worked anywhere he could get a job, bars, nightclubs, furniture stores – and then he got the opportunity to work as a stylist’s assistant for Rachel Zoe, a mentor.

In 2011, he left the world of fashion and jewellery, and opened his own studio, Jeremiah Brent Design, now based in L.A. and New York. In addition to countless residential projects across the U.S., he has also designed restaurants (such as Juliet in Los Angeles), retail shops (True Botanicals, San Francisco), offices (for film/TV producer Ryan Murphy in Hollywood) as well as one of his favourites, reimagining the interior of Covenant House in Los Angeles, which is situated across the street from his first apartment in the city, after spending almost a year living in his car.

Brent, right, says his fascination with homes began when he was a child. On weekends, he and his mother would go on home tours, 'checking out the open houses for homes we could not afford.'Paolo Abate/Supplied

For many years, he believed design was “the most important thing in the world. I thought it could change your life.” He still thinks it can, “to some extent.”

However, marriage, children and the process of writing the book have shifted his perspective about what makes design powerful. “It’s not about opulence, or pedigree, or fancy, expensive things,” he says. “It is about this idea of permanence, of feeling people’s lives the minute you walk into a room. Like when you can instantly tell that people have been up until two in the morning smoking and laughing, or when you see a side table with so many picture frames on it, that there isn’t room for anything else. That is real beauty in design.”

As someone who spent a sizable portion of his career in design television – where everything is transactional (“It’s all about how you can flip it, twist it and turn it”) – this new perspective is refreshing. “Doing this book has completely changed the way I create,” he says. “It’s also shifted the way I look at our homes. I see scratches on the baseboards now and I don’t want to paint them over because it reminds me of the morning we were on the floor, and I was tickling the kids.

“Home to me now means a place that embodies who we are, what we value and supports who we hope to become.”