They come from all walks of life, and all professions, and have spent hundreds, if not thousands, of hours building everything from Egypt’s Great Sphinx of Giza, the Ottawa Hospital, the Stanley Cup and Schitt’s Creek’s iconic Rosebud Motel. They congregate regularly to showcase their creations at fan expos around the globe. And some have even been invited to display their work at prestigious art shows such as Art Basel.

Meet the AFOLs, as they are known in Lego lingo – Adult Fans of Lego. And since the pandemic, their numbers have grown exponentially as grown-ups discovered – or perhaps, rediscovered – the childlike joy that comes from playing with this beloved 91-year-old toy.

A couple of years ago, Genevieve Capa Cruz, head of product for adults at the Lego Group, says her company noticed that adults were buying more Lego kits than ever before. “COVID was an inflection point,” she says. “People were stuck at home, with nowhere to go, nowhere to spend their money and they were stressed out. They were suddenly looking for hobbies and Lego was a perfect way to drown out the noise of the everyday.”

The iconic Rosebud Motel from Schitt’s Creek.Supplied

Recognizing the untapped potential in the 18-plus age category, the family-owned Danish company started to develop more adult-friendly products that came with a healthy dose of nostalgia (after all, very few kids have made it through childhood without snapping two Lego bricks together). Soon shelves were stocked with kits such as the Central Perk café from the sitcom Friends, vintage 1989 Batmobiles, Ghostbusters headquarters and the iconic Volkswagen T1 Camper Van. They also developed a new tag line, “relax, build and find your flow.”

Including adults in the company’s strategy has only helped. For the past nine consecutive years, Lego has been ranked the world’s most valuable toy brand, with a valuation in February, 2023, of US$7.4-billion, according to U.K.-based consultant Brand Finance. Capa Cruz declined to say what percentage of Lego users are now 18-years-plus (“It is a very healthy audience base which continues to grow”) or what percentage are women (“It used to be Lego was predominantly used by boys and men but now it’s young girls and women, too”). However, alongside the perennially popular Star Wars and superhero kits, recently launched product lines include botanicals and home decor.

And it seems that adult enjoyment of Lego continues to grow. In 2022, the Lego Group conducted a Play Well Study, polling 33,429 adults in 33 global markets (including more than 1,000 Canadians) about the benefits. It found 67 per cent of Canadians said Lego helped them relax, 71 per cent said it kept them mentally sharp and 71 per cent said it promoted creativity. Canadian Lego fans also said the toy gave them transferable skills for everyday life.

One such fan is Kelowna’s Stacey Roy, who played with Lego as a kid and then reconnected with the colourful bricks in 2020 when she was bored during the pandemic lockdowns. On a whim, she bought a Star Wars kit. “I started to stream videos of myself building the Millennium Falcon and my followers loved it,” says the 35-year-old creator of the Nerdy Bartender on YouTube and Amazon’s Cooking with Stacey.

Kelowna’s Stacey Roy played with Lego as a kid and then reconnected with the colourful bricks in 2020.Supplied

What Roy also discovered was how good playing with Lego was for her mental health. “Lego, for me, is a wonderful creative outlet and incredibly relaxing.” She kept building structures – piece-by-methodical-piece – and two years later found herself on the third season of the Fox TV show Lego Masters. She and a partner (Nick Della Mora from Toronto) won the US$100,000 contest.

Now she travels across North America judging Lego competitions, moderating panels at Comicon in Las Vegas and working as a spokesperson for eBay, which sells rare or discontinued Lego kits that can resell for up to $6,000 (such as the vintage architectural kit called the Café Corner).

Roy is not the only one who has found playing with Lego – which in Danish means “play well” – to be deeply rewarding. Ottawa physician Lucie Filteau calls her relationship with Lego a “hobby on steroids.” When she started building Lego as a way to spend quality time with her sons she never imagined the tiny bricks would become such an important part of her life. “I was in my mid-40s when I took it up,” says Filteau, an anesthesiologist at the Ottawa Hospital, Civic Campus. “The kids would go to bed and I would keep going. It was a way for me to unwind.”

However, what started as a reprieve from a busy life soon turned into passion. “Playing with Lego has enabled me to look at the world differently now. I notice the details and the beauty in things that I didn’t see before.”

For instance, the 55-year-old spent four months building a replica of the 100-year-old hospital campus she works at. “I’d walked in and out of this building for 15 years and I had never really looked at it. Lego helped me slow down and appreciate what is right in front of my eyes.”

Ottawa physician Lucie Filteau calls her relationship with Lego a 'hobby on steroids'.Courtesy of Lucie Filteau/Supplied

The process also reinforced for Filteau how important it is to carve out downtime. “In health care there has been so much pressure in the last few years and working conditions have been so challenging. My hobby became an antidote to burnout. It protected me in terms of my own wellness, and it helped me create a better balance between work and play.”

In fact, Filteau’s intricate builds have even unexpectedly tied into her professional life after landing her on the news. “TV interviews are something I would never have considered doing before. When I applied to be president of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society, they asked if I had any media experience. I said I do, but it’s not related to anesthesiology and it’s certainly not what you’d expect!”

Some die-hard adult fans such as Graeme Dymond have given up their day jobs to pursue Lego full-time. Shortly after being named Canada’s first Legoland Master Model Builder in 2012, Dymond left a career as a corporate trainer at a major bank to launch his Mississauga-based company, Dymond Bricks. For the past 12 years he has been building structures – big and small – for companies ranging from Google, Toronto Dominion Bank, Mazda, Pepsi, General Electric, Costco and Amazon, which use them for marketing and promos.

Dymond, who is a Lego Certified Professional (LCP), says he has never regretted trading in his “cubicle for little cubes.” (An LCP is an artist officially recognized by the Lego Group as a professional builder. There are only 22 in the world and they are selected based on their building proficiency and enthusiasm for all things Lego.)

Some die-hard adult fans such as Graeme Dymond have given up their day jobs to pursue Lego full-time.Supplied

“In the high-tech world we live in, there are so many screens drawing our attention. I believe there is an innate need in us, as human beings, to create and build,” says Dymond, who hosts an adult Lego conference called Bricks in the Six, which last year drew 3,000 attendees from across Canada. “I think of Lego as a form of storytelling. It fulfills the need for people to express themselves and it connects people. It’s inter-generational and all-inclusive.”

Robin Sather, of Abbotsford, B.C., agrees. “I was a Lego kid from a very young age, and I never really grew out of it,” explains the 58-year-old entrepreneur, who was crowned the world’s first Lego Certified Professional in 2005. He, too, left a “regular” job in information technology almost 20 years ago to build Lego for a living. His company, Brickville DesignWorks, which builds Lego creations for companies and hosts Lego events, has never been busier. “I’ve seen first-hand how much the adult market has grown.”

“The number of people doing Lego-based work at an advanced hobby level, or even a professional level where they’re making a good chunk of their income from it, is 40 times what it was two decades ago,” he says. “And the bar keeps being raised. The level of artistry and technical wizardry is amazing.”

Katherine Duclos started using Lego bricks as an artistic medium after her autistic son handed her four bricks because he thought she would like the way the colours worked together.Dorothy Hong/Supplied

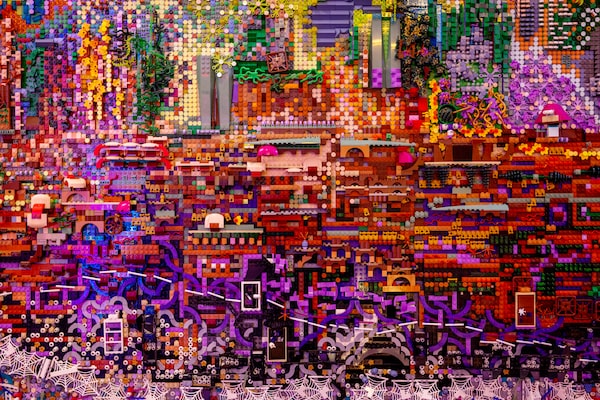

American-born multidisciplinary artist Katherine Duclos started using Lego bricks as an artistic medium after her autistic son (“He was a savant at building Lego kits at the age of 3”) handed her four bricks because he thought she would like the way the colours worked together. She was instantly inspired. “I had this aha moment when I realized the tiny colourful pieces, which come in so many shapes and sizes, would be perfect for my abstract constructions.”

Duclos started small with Lego constructs mounted on coloured paper, framed and shown at Kafka’s Coffee, a popular café/gallery on the Emily Carr University campus in Vancouver, where she lives. The café patrons were captivated. Using the simple bricks helped Duclos regulate and process the intense sensory overload she experiences as an autistic person with ADHD. Then, one of her pieces went viral on Instagram. About six months ago, curators with Art Basel, Miami Beach, came calling.

In early December, Duclos had several pieces – including one 10-foot-long mural called Where There Are Roots – at the prestigious show. The artist credits Lego’s ability to spark the imagination for getting her there.

Artwork from Katherine Duclos.Dorothy Hong/Supplied

“The bricks are the foundation that enables creativity to thrive. They offer autonomy, an ability to see an idea to fruition, and to think big and detailed at the same time. When we know we are capable of building our own ideas, we get into a habit of letting them grow.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly said Ottawa anesthesiologist Lucie Filteau spent six years building a replica of her hospital; this version has been corrected.