Years before the Elf on the Shelf, in the late 1950s, Montrealer Eileen Martin came up with the story of Blinky, a benevolent elf who encouraged her seven kids to be their best selves.Supplied

A colourful advent calendar is a December treat in many households. But in the Martin family, instead of receiving a daily chocolate, you get accountability.

Every morning leading up to Christmas, each child’s calendar records the previous day’s behaviour, with a sticker for the nice, a red X for the not-so, and sugar for no one. That decades of Martin children have not instigated some kind of holiday mutiny is entirely owing to the storytelling prowess of the family matriarch.

Years before the Elf on the Shelf, in the late 1950s, Montrealer Eileen Martin came up with the story of Blinky, a benevolent elf who encouraged her seven kids to be their best selves, keeping a record of how they did each day as the holiday approached. The story she told was passed down, and the tradition has continued among her 17 grandchildren and 10 great-grandkids.

“Other kids at school didn’t have Blinky,” Eileen’s grandson Stuart Martin says. “It made us feel even more special.”

'Other kids at school didn’t have Blinky,' Eileen’s grandson Stuart Martin says. 'It made us feel even more special.'Supplied

The winter holidays are stacked with well-worn traditions – tree-trimming, candle-lighting, gift-giving and more. But for many families – both biological and chosen, mine included – it’s the invented customs that truly mark the season, the little oddities that are all their own.

Some of these made-up traditions have worked their way into popular culture. The toy narc Elf on the Shelf also began as family lore around their own pixie doll, before the inventors later turned it into a product. The utterly bonkers alternative holiday Festivus, featured in a classic Seinfeld episode, was inspired by one of the sitcom’s writers, Dan O’Keefe, whose father subjected the family to his invented traditions at random times of the year.

The fictional Festivus was celebrated with “feats of strength,” an unadorned metal pole in place of a tree and an “airing of grievances” among family members. In a 2021 podcast interview, O’Keefe explained that it was not a happy memory, but despite its origins, he spun Festivus into comedic riches.

For some, unique traditions come from the blending of cultures. When Marcus Handman (reared on Hanukkah) and his wife, Gwen Maroon (of the Christmas persuasion), had their first child 40 years ago, they wanted a compromise that would still provide a bit of magic for their kids. While the Victoria residents are not the only ones to celebrate the winter solstice – an ancient and global tradition, from which many mainstream holiday celebrations borrow – Maroon invented the Solstice Fairy.

On the morning of Dec. 21 each year, their children would wake up to a present at the foot of the bed, delivered by the Solstice Fairy during the night. Maroon put together a book about the fairy, with hand-drawn illustrations, to read to them every year.

“Gwen really wanted them to have that little bit of magic, and something that was a little bit otherworldly, and wasn’t part of their day-to-day reality,” Handman said. “The fairy gave them that sense of wonderment.”

The Solstice celebrations were common ground for their multifaith family. Still, certain rituals with pagan roots have acquired a distinctly Christmas mien – such as the Solstice bush they decorated with nature-themed ornaments. One year, when his Jewish parents visited, Handman put up a sign, “I am a Solstice Bush,” to emphasize that it was definitely not just a slightly stunted Christmas tree. “I’m not sure my mother bought it,” he recalls, laughing.

Collin Ashton’s family has not invented any fairies, but they do have Christmas Gold, an unconventional gift exchange that sees Ashton and his wife, Gail Trayler, both retired, combing through estate sales, thrift stores and garage sales all year long for the stupidest presents they can find.

When the family of 21 gathers at the couple’s home in Langley, B.C., the exchange unfolds with great ceremony, each person choosing an unidentified wrapped present and displaying their surprise “treasure” for the group.

Collin Ashton’s family comb through estate sales, thrift stores and garage sales all year long for the stupidest presents they can find.Supplied

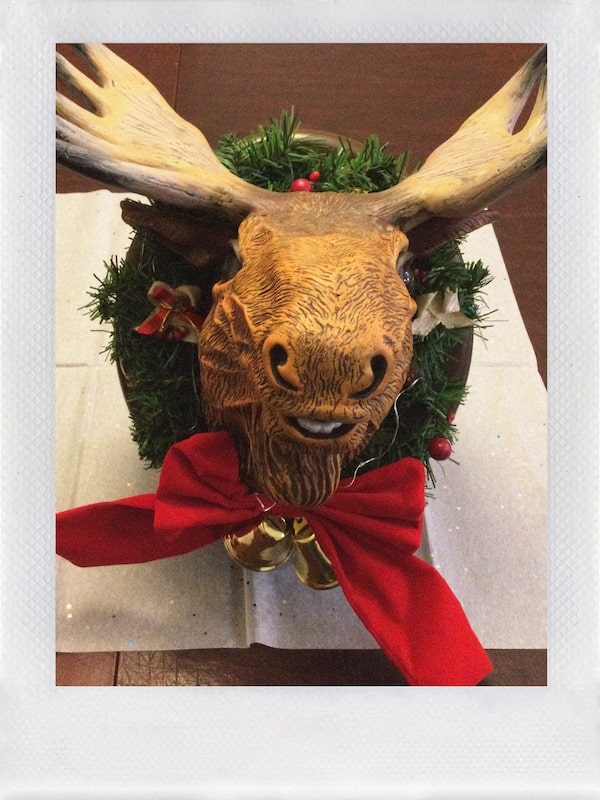

When they congregate this December, one family member will unwrap a plastic hunting trophy of a moose (think Big Mouth Billy Bass, but bigger and Christmas-themed) with a red ribbon and bells around its neck. And yes, it sings.

But despite the teasing – Ashton’s kids have their own name for the gag gift exchange, which uses an off-colour word instead of “gold” – the tradition has been going strong for at least a decade. Ashton hopes it will outlive him.

“That’s what makes it so worthwhile, it’s those memories that the kids have, and will talk about for years to come.”

When Collin Ashton's family congregate this December, one family member will unwrap a plastic hunting trophy of a moose with a red ribbon and bells around its neck.Supplied

At a time when the world can seem very dark, stressful and uncertain, familiar customs – even silly ones – can carry a deeper importance, says Dimitris Xygalatas, head of the University of Connecticut’s Experimental Anthropology Lab, and author of the book Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living.

“Our brain really abhors uncertainty. And if ritual is anything, it is structure and predictability,” he says. “It gives you a sense of comfort, because it provides a sense of control over the chaotic world that we live in.”

In experiments, Xygalatas observed that after performing familiar rituals, people’s levels of cortisol – a hormone linked to stress – drop.

Crucially, he says, the rituals we create connect us to our families and to wider communities.

I have seen this firsthand in the odd little ritual my family created.

About 50 years ago, my parents began getting together with another couple each year to celebrate Hanukkah. When children later arrived, possibly to keep them interested in the proceedings, the adults talked up a fake competition to see whether the Krashinsky or the Greenberg family’s Hanukkah menorah (or hanukkiah) would burn the longest. And the Great Menorah Race was born.

The Krashinsky and Greenberg families compete in the Great Menorah Race.Susan Krashinsky Robertson/Supplied

The stakes could not possibly be lower. For a while there was a prize, but even that has fallen by the wayside. We are in it for the love of the sport. Whenever the Greenbergs bring one hanukkiah with particularly deep wells – an unbeatable behemoth we have bitterly nicknamed Seabiscuit – the despair is palpable.

Over the years, the race has taken on strict rules (all candles must be of a uniform type and size; storing candles in the freezer is decidedly taboo; each person lights a hanukkiah of the opposite family to ensure no dilly-dallying to gain an advantage). And it has grown, as each family member acquired their own hanukkiah.

“I definitely want to give a shout-out to the year that we gathered so many hanukkiot on one table that the smoke alarms went off and ever since, protocol requires their dispersal,” my brother, Jon Krashinsky, says.

This year, we will gather once again. After decades of creating this mild fire hazard together, the Greenbergs seem less to me like family friends, and more like family.

And over time, these traditions we create provide a link to the past. There are hanukkiot on our table that belonged to family members who have left us. They are still part of our gathering, lit up bright – and often losing to Seabiscuit.

Stuart Martin, checking out his nieces' Blinky calendars.Supplied

For the Martin family too, a made-up tradition keeps them connected. This will be their first Christmas without Eileen, the imaginative raconteuse who conjured their unique ritual. She died in May, at the age of 99. But Blinky is still here: Stuart Martin and the rest of the family have prepared the calendars for her great-grandchildren, and are recounting the story as they always do.

“We’re going to all be gutted, that she’s not here with us this year,” he says. “But at the same time, having this tradition to share with all of the future generations, and all of our friends and family, what more could you ask for?”