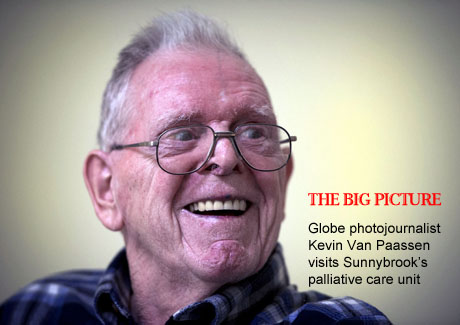

Patient Donald Parr is seen in the palliative care centre at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario, Wednesday December 25, 2013.Kevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail

David McMaster was dying. What shocked his family was the way it happened.

"We were robbed of the chance to say a proper goodbye," says his daughter Susan.

Mr. McMaster, 80, had been in and out of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in 2010 with a series of complex circulatory and kidney problems. Eventually he also contracted C difficile, a hospital based-infection. After a week in the Intensive Care Unit on a breathing machine, doctors decided nothing more could be done; it was time to move him to "comfort care."

But the only available bed was on a general medicine ward with two other patients. So instead of a peaceful atmosphere, Mr. McMaster ended up in pain, gasping for breath in a tiny room noisy with boisterous visitors and clanging cell phones.

Even worse, Mr. McMaster's daughter couldn't rouse a nurse or a doctor in the middle of the night – so she watched her father struggling "for a gruelling" 90 minutes before he was given appropriate sedation. He finally fell into a deep slumber, but Susan kept guard for the rest of the night and remained with her father until he died later that afternoon.

"I wouldn't want this to happen to my mortal enemy," she says.

Most people envisage soft music, gentle lights, and family and friends swaddling them in love as they are ushered from this world into whatever lies beyond, but the ghastly reality that the McMaster family experienced is far too common. Instead of stewing over her father's death, though, Susan McMaster decided to be proactive and present her case to the hospital.

Her complaints challenged Sunnybrook to rethink end of life care. They also speak to a much bigger challenge – to redefine what a "good death" looks like, both in and out of hospital, in time to support a rapidly aging population. And to reconsider our own responsibility for planning life's last big milestone.

Inevitable, unpredictable

Perhaps the other end of the life cycle offers us some guidance.

Birth used to happen at home. Then modern medicine intervened and what was once a natural event became institutionalized. In the process maternal and infant mortality dropped, which was a good thing. But women wanted both safer childbirth and more say in their experiences, so they agitated for change.

Nowadays, women have a variety of choices about how they give birth. Some routinely go into labour at home, supported by midwives, and give birth in their own beds. Others start at home but head to a hospital when contractions are acute, deliver the baby, and leave a few hours later. Still others plan caesareans, or hospital birth with enough drugs not to feel any pain during labour and delivery.

Death, too, started at home. But now 65 per cent of Canadian deaths every year occur in hospitals – even though how we want to die is as varied as patients themselves.

Some of us will fight disease to the end with chemotherapy drugs coursing through our their veins. Others will opt for terminal palliative sedation – an induced, coma-like state to ease anxiety and ragged breathing before death. And a great many of us, especially seniors who are aging in their own homes, want to die there, or in a hospice.

Unlike pregnant women, though, dying patients don't have a due date.

Doctors are notoriously bad at predicting when their patients are going to die. Only 20 per cent of survival estimates were accurate in a British Medical Journal study of nearly 500 patients admitted to hospice in 1996.

The late American humourist Art Buchwald so befuddled the mortality prognosticators that he wrote a bestselling book, Too Soon to Say Goodbye, about the time he spent not dying in a Washington area hospice. After being shown the hospice door, he finally succumbed to kidney failure several months later at his son's home.

Patients who don't die on cue can bedevil hospital administrators managing tight budgets and juggling beds in chronically stretched units. Donald Parr, a gentle, amiable man in his mid-80s, was admitted to Sunnybrook's 32-bed palliative care unit last October. Typically, patients die within 18 days of admission, but Mr. Parr, like Mr. Buchwald, defied the odds. The hospital wanted to send him home or transfer him to a less expensive bed in another facility.

"I survived the three month sentence, so I can leave," Mr. Parr said in early December, putting a genial public face on news that had shocked him and his family.

But where was he supposed to go, after moving out of his nursing home to die in hospital? Mr. Parr, a former mechanic for Massey Ferguson, was happy on the palliative care unit at Sunnybrook. Having buried two wives, he knew what death looked like, and it didn't "scare" him. What worried him, though, was being a burden.

The hospital finally agreed to hold off on the discharge paperwork until after the New Year. With that reprieve, the Parr family gathered to celebrate Christmas dinner in the unit, but his son Robert says Mr. Parr "never ate a bite." Living in a shared room – three roommates expired in as many weeks – probably didn't help. Mr. Parr died on Jan. 17, two weeks after his 87th birthday.

Mr. Parr's son has nothing but praise for the nursing staff. But he still can't understand why his father's final weeks had to be so anxious. "I saw the stress and the worry come over his face when they tried to move him," he said. "He barely got out of bed after that."

Talking about the end

Mr. Parr's experience might have been different if somebody had asked him the right question before moving him from a nursing home to palliative care.

The "surprise" question – "Would you be surprised if this patient were to die within the next three months?" – is the new standard for determining if a patient is actively dying. It improves on using only lab results and MRIs to consider patients, and their social, emotional and cultural circumstances.

That point was codified in a 2010 study in the New England Journal of Medicine, comparing two groups of patients with metastatic lung cancer. Half were given palliative – or patient-centred – care in addition to standard oncological treatment. They reported a better quality of life and less depression. They also survived longer than their counterparts, even though they had less aggressive treatment.

What this study suggests is that the best prescription for end of life care may be the oldest analgesic in the world: listening to patients, talking to them about their wishes and their goals, and balancing hope (if not for a cure, then for an easeful death) with practical discussions about treatment.

Listening to Ms. McMaster was pivotal for Sunnybrook's new approach to end of life care. "This patient's story had a huge impact on us," says Ru Taggar, Sunnybrook's chief nursing executive and vice-president of patient safety. Ms. Taggar launched a critical care review and invited Ms. McMaster to participate.

"That was the first time we had a family member present for every single meeting we had about this case," says Dr. Jeff Myers, head of the Palliative Care Consult Team at Sunnybrook. And out of that review, the hospital launched what it calls its Quality Dying Initiative, an institution-wide approach to putting patients (and their loved ones) first in the hospital's approach to the end of life.

But Dr. Myers doesn't think hospitals are the only ones who should be talking to patients about death. He says family doctors and other primary health workers should routinely inquire about our life goals in annual check-ups. "Because they may change over time," he explains.

That doesn't negate the need for a clear (and legal) advance care planning document, financial and medical powers of attorney, and all the other end of life paraphernalia, but a record of evolving conversations with healthcare professionals is a boon for substitute decision-makers faced with representing your wishes after a catastrophic decline.

That is one of the lessons from the Supreme Court decision about Hassan Rasouli. After surgery at Sunnybrook to remove a benign brain tumour, he suffered extensive brain damage from a post-operative infection and was put on life support in the hospital's Intensive Care Unit. His physicians, who believe Mr. Rasouli is in a persistent vegetative state, wanted to disconnect him from the machines and transfer him to palliative care.

But his wife, Parichehr Salasel, refused, and after an impasse, both sides sought legal remedies. The case ended up in the Supreme Court of Canada, which ruled 5-2 against the doctors, arguing that they should have petitioned the Consent and Capacity Board (the organization charged with arbitrating such end of life disputes) for a ruling before heading to the law courts. More than three years after his catastrophic infection, Mr. Rasouli continues on life support in the ICU, a daily cost of about $3,000 a day, instead of the $340 price tag for palliative care.

The Rasouli case is an extreme example, but it underlines how important it is for all of us to decide, long before we merit the descriptor elderly, what we want in terms of end of life care. Dying was never as simple as breathing or not breathing, but now we have to contend with various forms of death in life.

At home

Living will, and programs like Sunnybrook's Quality Dying Initiative try to improve the way people die in hospital – the how of death. There are also efforts to improve on the "where" of death.

John McDermott, whose soaring tenor brings tears to veterans and their families when he signs Danny Boy in Remembrance Day ceremonies, is raising money to refurbish and expand the Palliative Care wing at Sunnybrook to include private rooms for patients and better working and sleeping facilities for families who want to "live in" while loved ones are dying.

Like so many benefactors, he has a personal incentive for giving. He comes from a military family and he promised his father long ago that "if he ever made it big [in the music business] he would do something special for veterans." So far he has raised more than $1 million through concerts and online appeals for the palliative care unit; an architect is expected to be named soon.

But the end of life can't be managed by hospitals alone. It takes money away from spending on the acute care they can provide – and it isn't always the right environment for a good death. That's why Ontario's Local Health Integrated Networks, the 14 regional administrative bodies through which funding flows to hospitals such as Sunnybrook, are committed to reducing the number of days patients spend in hospital palliative care units by 10 per cent. Part of their plan is to set up a system-wide registry of palliative care beds so that the needs of dying patients can be matched to an appropriate level of care. They also want to offer greater support to hospices and homecare.

For many of us (see Globe poll) home is where we want to die. That is Bridget Sine's wish.

On a sunny but frigid winter afternoon, she received me in the bright bedroom of her two-story Victorian home in Toronto. The walls, which have been painted an azure blue, are decorated with her own drawings. Photographs and mementoes compete for space with medicines, a pole for helping her get in and out of bed and a chair for visitors.

Married with two young daughters, Ms. Sine was only 43 when she was diagnosed with a chordoma in the sacrum area at the bottom of her spine. She underwent radiation, extensive surgery and a painful recovery. But that reprieve was short. Four years later she is now in palliative care.

That doesn't mean she has given up. She gets support from jer local Community Care Access Centre and Hospice Toronto – including volunteer visits from a retired nurse, an art therapist and even a massage therapist who came to her home for a Reiki session. She no longer hopes for a cure, but she is determined to live her life as fully as she can and intends to stay at home until the end. If that's not possible, and for many people it isn't, either because of intractable pain or other symptoms, she will end up dying in a residential hospice or an acute care hospital.

Meanwhile, she has taken charge of her own death. Just as Ms. McMaster hopes other patients in hospital can do now – despite her father's experience. We only get one shot at dying. There is no practice round.