no creditno credit

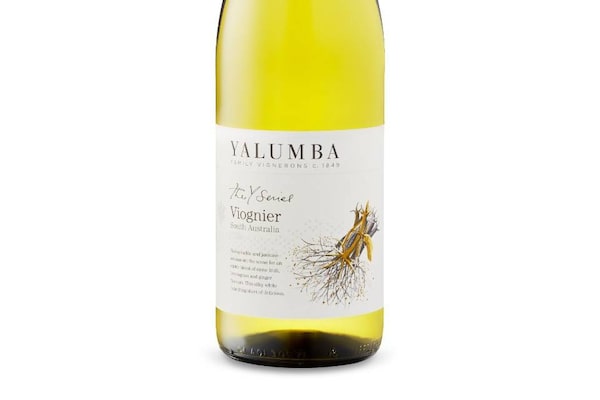

The average wine shopper might be drawn to Yalumba's The Y Series Viognier for any of several reasons. It's a consistently good buy, as low as $13.95 in Ontario and up to $18 in Nova Scotia. It's made by a leading Australian company that has been in family hands for 169 years. And, for the growing market of grape hippies, it's fermented the old-school way, with wild yeasts rather than laboratory-cultured strains.

But look closely at a bottle of the newly released 2017 vintage and you'll notice a more peculiar distinction. A sticker on the front label reads: "Vegan Friendly."

The Y Series Viognier, like all Yalumba wines and most produced by its sister company, Hill-Smith Family Vineyards, was crafted without resort to animal-derived additives. If that sounds like a superfluous boast for a product ostensibly made only from crushed grapes, you've been out of touch with the great carnivorous-wine awakening.

Over the past several years, the mass market has – with reactions ranging from bewilderment to horror – begun to wise up to a long-standing open secret. To clarify sediment, producers often add such goodies as egg whites, milk protein and even a gelatin obtained either from livestock parts or sturgeon bladders. Those additives all fall into a category known as fining agents, materials with the magical ability to bond to large grape-residue particles, form clumps and draw the gunk out of solution.

Growing awareness of the process, combined with the mainstream acceptance of plant-based diets, has begun to prompt change. More vino is going vegan. Or, at least, some that already was is having its coming-out party.

At Yalumba, while every bottle has been vegan-friendly since the 2012 vintage, labelling to that effect began only with the 2016-vintage Y Series wines and has since expanded to include The Scribbler, a $24 cabernet sauvignon-shiraz blend. "Not all our wines are labelled vegan-friendly," said Pippa Merrett, public-relations manager with Yalumba and Hill-Smith Family Vineyards, "but it is indeed a great point of differentiation." The company's other vegan-friendly brands include Pewsey Vale, Oxford Landing, Heggies and Dalrymple.

While Yalumba has begun applying aftermarket stickers and printing vegan-friendly claims on back labels, some wineries are wearing the distinction more conspicuously. The Vegan Vine, an offshoot of Clos LaChance Winery in California, was an early pioneer. The brand has since attracted a high-profile ownership partner, former NBA basketball star, wine lover and 6-foot-11 vegan John Salley.

In Canada, the nod for most progressive marketing must go to Summerhill Pyramid Winery, an organic and biodynamic estate in Kelowna, B.C. Chief executive officer Ezra Cipes says that although all their wines have been zoologically free (with the exception of manure used to fertilize vineyards) for more than a decade, a decision was made only recently to place the word "vegan" prominently in the centre of labels for its mass-market Alive brand. It was done, he says, at the urging of a category manager at BC Liquor Stores.

"He said that the most-asked question on the floor [of stores] was for vegan wine, more than [for] organic, more than for anything," Cipes recalled. "People were asking for vegan wines." Given that his wines already happened to be vegan, the manager recommended Cipes put it in writing. "And so we did. And it generated a lot of discussion and by the next year we started putting it on all our labels."

For the record, I contacted BC Liquor Stores for an interview with the manager in question. but the request was declined. As for the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, I was told the huge retailer does not track vegan-labelled products as a category within its database.

Indeed, if you type "vegan" into the search engine of a Canadian liquor board's website, you'll find almost nothing there. And yet the number of vegan-friendly wines is huge. Take the typical case of a popular Portuguese red, Animus Douro from the good-value producer Vicente Faria ($11.85 in Ontario, $13.49 in British Columbia). It's vegan and also gluten-free, but not explicitly labelled as such, at least not for now. Angeline Prodhon, the marketing and business-development manager for its Ontario importer, Profile Wine Group, told me she is working on a sticker to add to bottles. And here's a tip: If you see "unfined and unfiltered" on a label, which is becoming increasingly common among premium wines, you can be reasonably confident the product is animal-free (though it's best to check with the winery).

One of the best sources on the subject is Barnivore.com, which lists more than 3,400 vegan-friendly wines and wine brands around the world, some of which are fined with mineral-based materials such as bentonite, a form of clay, and some not at all. The 11-year-old database, compiled through crowd-sourcing by site visitors who submit a cut-and-paste questionnaire to wineries they're interested in, is maintained by Jason Doucette, a former volunteer with the Toronto Vegetarian Association's Resource Centre. "On any given day there'll be two to 10 submissions in the queue, some from regulars who've made it their mission to reach out to their local areas, and many from people who've never submitted before but want to help fill a gap they've found," Doucette said.

It may be a fringe category now, but vegan-friendly labelling is bound to become more common. According to a survey released in March by Dr. Sylvain Charlebois, a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University in Halifax, 2.3 per cent of Canadians, or roughly 850,000 people, consider themselves vegan. That's a jump from previous surveys that had pinned the figure at 1 per cent, Charlebois told me. Moreover, 51 per cent of Canada's vegans are under 36, which suggests the numbers are destined to grow. "There's a bright future for anyone catering to these markets," he said.

Curiously, for wine drinkers in Canada, the animal-additives issue started to come into sharp focus years ago (around the time I wrote a story in 2011), for reasons unrelated to veganism. In 2012, to address concerns from people with severe allergies, Health Canada introduced strict regulations relating to fining agents in wine that prompted many producers to slap such odd warnings as "contains eggs," "contains milk" or "contains fish" on back labels. (Never mind that the specific purpose of a fining agent is to form clumps that can be removed beyond detection and that conclusive evidence of allergic reactions to such substances in wine has been slim to non-existent.)

Most vegans are concerned with more than just health, however. Many adherents are motivated out of concern for animal welfare. (Each vegan spares about 200 animals per year, according to the University of California, Davis's department of integrative medicine.) For still others, it's about the environment, given that it takes far more energy and acreage to feed the world with carbon-producing livestock than with plants. Though even here a dogmatic vegan might disapprove of an organic estate that uses beasts of burden to pull compost sprayers.

Cipes at Summerhill says he's happy to wave the vegan banner for a couple of reasons. It's a way to serve vegans (his father is one), who otherwise would be left in the dark because wine, unlike most packaged foods, carries no ingredients list. Also, it's a way for the winery to "hint that this is a minimal-intervention wine," he says.

Meanwhile, there will always be producers who prefer to give a wide berth to the vegan label even if they eschew eggs, milk and gelatin. As with the early days of "organic," the word can carry a stigma – of Birkenstocks and righteousness versus vinous decadence.

Cipes says he's had "a little bit of blowback" from chefs regarding his new labels. He says they don't want the word "vegan" displayed prominently on wine bottles at their restaurant tables because they make more money on meat entrées than on salads. As an omnivore, Cipes appreciates the concern. At the same time, he is happy to offer something to consumers who are following their hearts. "I wish it wasn't at all divisive," he says. "I wish people wouldn't see it as a moral statement."

Wines to try

A small selection of reliable, vegan-friendly brands:

- Alois Lageder, Italy

- Astrolabe, New Zealand

- Avondale Sky, Nova Scotia

- Bacalhoa, Portugal (including Alianca and JP Azeitao brands)

- Bench 1775, British Columbia (2014 vintage onwards)

- Bellingham, South Africa

- Bodegas Castano, Spain

- Bonny Doon, California

- Boschendal, South Africa

- Chapoutier, France

- Church & State, British Columbia

- Creekside Estate, Niagara (2016 onwards)

- D’Arenberg, Australia (red wines)

- E. Guigal, France

- Flat Rock Cellars, Niagara (2013 onwards)

- Georges Duboeuf, France

- Hugel & Fils, France

- Kaiken, Argentina

- Moon Curser, British Columbia

- Nicolas Feuillatte Champagne, France

- Southbrook, Niagara

Source: Barnivore.com