Impossible is a word often used to describe chef Magnus Nilsson's dream to operate a world-class restaurant in Jarpen, Sweden, a northern locality on the 63rd parallel – think Frobisher Bay or Davis Strait in Canada.

But Faviken, the restaurant whose name rolls off the tongue like butter among food lovers, wasn't in the plans when he left Stockholm to travel north to his childhood home in the subarctic terrain. The rugged landscape and sparse population were a tonic. Weary of city living and disenchanted with a career spent parroting dishes and techniques he'd learned in France, he was initially hired to oversee the restaurant's wine cellar. In time, he took over the kitchen.

But the restaurant as it is today didn't manifest itself overnight. He and the space evolved together. Faviken was Nilsson's homecoming. "I wouldn't have said yes to someone who proposed this kind of project," he says. "I wasn't supposed to stay."

Chefs who choose to work and live in remote locations do so for any number of reasons. As with Nilsson, they're returning to hometowns or escaping the city grind and 15-hour workdays, or they fall hard for a place they discover on their travels. For most, the path less-travelled is a calling.

Most who find this kind of dream inconceivable come from cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Toronto and the experience of being in the middle of nowhere is in high-definition. "Faviken is not as remote as people think," Nilsson says. "It's no more difficult to travel to here than it is to travel to San Sebastian [in Spain] to eat." And transportation to Jarpen is far from formidable given that the Scandinavian ski resort of Are is within driving distance.

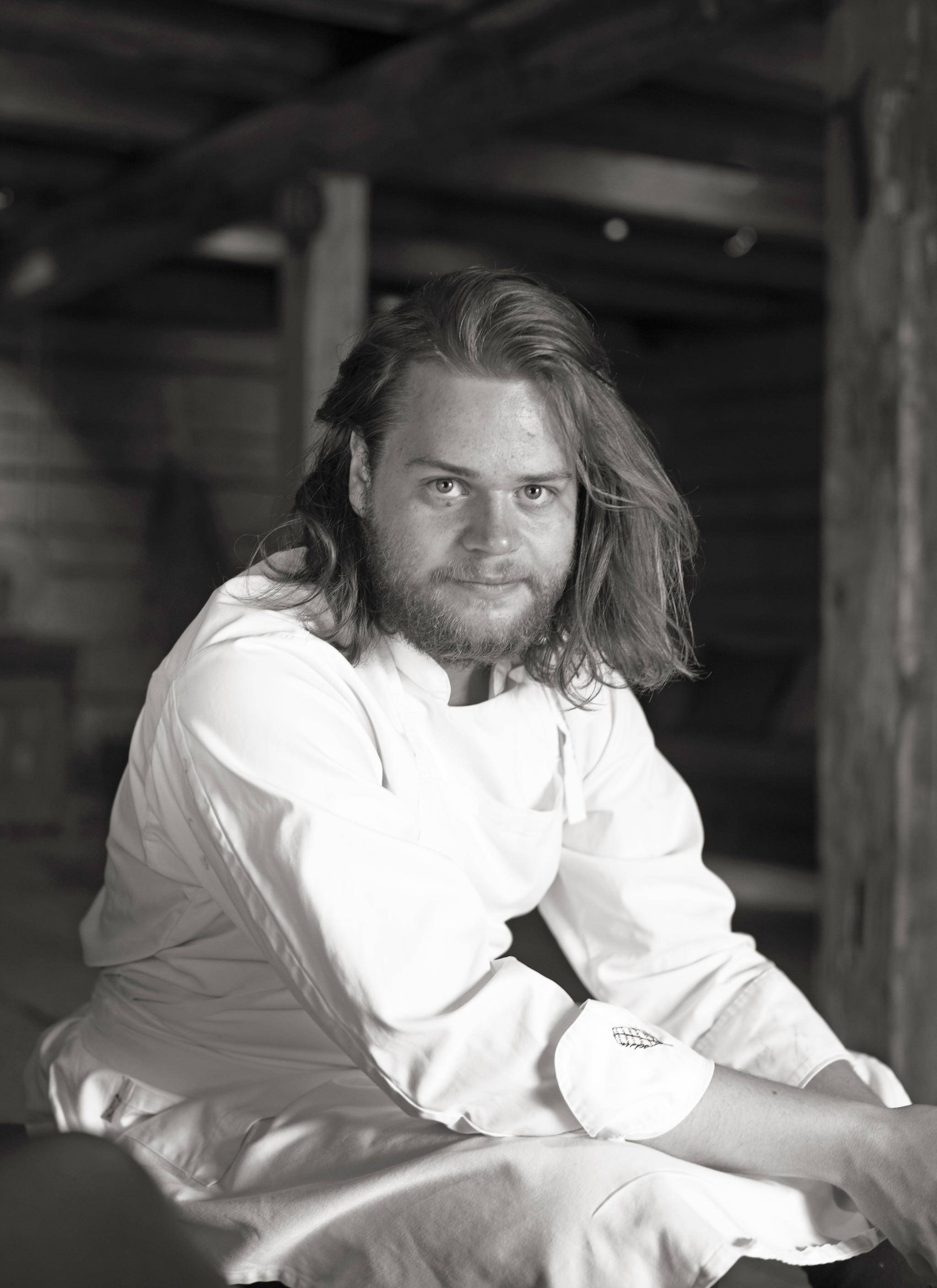

Faviken was a homecoming for chef Magnus Nilsson, but he says he wasn’t supposed to stay.

Erik Olsson/Faviken

In 1986, Michael Stadtlander had a eureka moment while sitting on the beach at Sooke Harbour House, where he was working, outside Victoria. He knew he didn't want to cook for hundreds of people or work crazy hours every night. Rising in him was longing for a garden and livestock and a farm like the one he grew up on in northern Germany. Along with his wife Nobuyo, they spent seven years searching in different areas across the country before settling on a farm outside Singhampton, Ont., a two-hour drive northwest of Toronto. "There were rolling hills and forests and little meadows," he says of the place they named Eigensinn Farm. "It was beautiful, and we were ready for it."

But the journey is integral to the experience for both those in the kitchen and the dining room. Kyumin Hahn, a Canadian chef who has worked in both Nilsson's and Stadtlander's kitchens, says of the guests at Faviken, "They haven't hopped in a cab to go to the restaurant; when they arrive they are there just to eat." The restaurants have in spades what most urban establishments long for: time to serve a leisurely meal without any distractions. The intimacy is distinctive – menus are small and seats are few – in stark contrast to the vastness of the wild location.

Stadtlander also recognizes another kind of hunger in his guests. "It's important to connect people with the natural world," he says. "That's why I'm still so busy; last year, I could have had two Eigensinn Farms."

The appetite for something different is also familiar to Cezin Nottaway. She's of Algonquin ancestry and is an Anishinabe First Nations chef from the Kitigan Zibi reserve in Quebec, about 135 kilometres north of Ottawa. She was taught the traditional ways of hunting, gathering and preserving by her grandmother and also came under the loving influence of a godmother who encouraged her to turn her skills in the kitchen into her life's work.

"I was scared out of my wits because I didn't know any young First Nations women who had started a catering business," she says. But there was not enough work on the reserve to support Wawatay Catering, so she set her sights on Ottawa, and the community there embraced her. She had the honour of serving lunch for students and residential-school survivors during the closing events of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. "Interest in First Nations cuisine is starting to grow," she says. "Other First Nations chefs are inspiring me and pushing me to do new things."

In remote locations local cuisine has real meaning. Cooking style owes as much to a chef's character as it does to the ingredients at their disposal. Katie Hayes of the Bonavista Social Club in Upper Amherst Cove, Nfld., points to the kind of resourcefulness the environment demands. "We are well-known for our moose burgers and have processed three whole moose this year," she says. Wild-game meat is such an innate part of Newfoundland food culture that it can be legally served in restaurants (unlike other parts of the country, such as Ontario).

Katie Hayes of the Bonavista Social Club in Upper Amherst Cove, Nfld., says the environment they’re in demands a kind of resourcefulness.

Brian Ricks

Clear across Canada, Lisa Ahier at SoBo in Tofino, B.C., found a perfect solution to another dilemma. "Vancouver Island is an oasis of farmland and products like lamb, vegetables and cheese, but getting it to us was challenging and costly," she says. "The local restaurant community banded together to form the Tofino Ucluelet Culinary Guild and fundraised to purchase a refrigerated truck." Since 2005, the island's bounty comes straight to her back door.

With few exceptions, most of these chefs have gardens and keep livestock. Magnus Nilsson's root cellar is almost as famous as his restaurant. They all speak with a kind of religious fervour about picking salad greens just before service or the pleasure of drying kelp. "We had a dish on the menu at Faviken that was only berries," Hahn says. "We'd pick them at 5:30 or 6 because they had to be warm from the sun."

They also face headaches that would baffle most city chefs. Stadtlander had to give up raising sheep last year because coyotes attacked his flock. And in Newfoundland, Hayes says, "We put ducks on our menu one year, and it was a disaster because they all got killed by foxes."

Pushing the boundaries on growing seasons and preserving methods is part of the pleasure. "The amazing thing about running a restaurant like Faviken, where we charge as much as we do, is it allows us to experiment; it's part of our function," Nilsson says. "You can push the boundaries a little more because you have the resources. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn't."

But before embarking on the journey, guests should probably know something about the destination. "Everyone wants to come to Tofino because they saw a pretty picture in a magazine, but it's rainy and wild, and there are cougars and bears," Ahier says. "You can't rent Jet Skis, there's no Tim Hortons, the internet connection can be sketchy."

Lisa Ahier of SoBo restaurant wants guests to know Tofino, B.C.,is ‘rainy and wild.’

But Hayes says that, once the panic of being in such a remote corner of Newfoundland subsides, "visitors are charmed by their proximity to nature – the wild coastline, the bald eagles, icebergs floating by in summer, and the whales."

There's a wholehearted commitment common in all the chefs to the life and work they've crafted. Michael and Nobuyo Stadtlander are celebrating 25 years on Eigensinn Farm this year and are busy laying plans for celebratory events, including the building of a new trail on their property. "It's a real privilege to do this," says Stadtlander. That's a sentiment shared by Nilsson. "You can feel when someone does something with a real intention because they really want to," he says, "It's heartfelt and overshadows almost everything else."

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the Globe Style e-newsletter, your weekly digital guide to the players and trends influencing fashion, design and entertaining, plus shopping tips and inspiration for living well. And follow Globe Style on Instagram @globestyle.