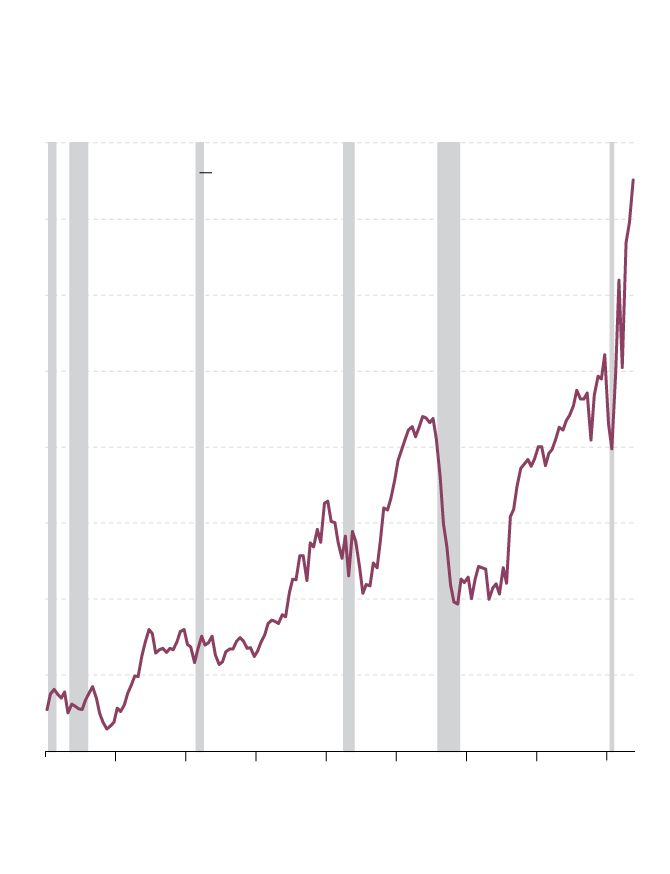

Everyone talks about how strong U.S. personal balance sheets are, but that is because of the unprecedented inflation in asset values, which have now gone parabolic.

Household net worth relative to disposable income surged from 797 per cent in the third quarter to an unheard-of 826-per-cent ratio in last year’s fourth quarter. A year ago, it stood at 760 per cent. When the pandemic started, try 665 per cent. Never before has the net worth-to-income ratio soared this much in a two-year span, and the data go back to 1948.

U.S. households and non-profit organizations:

net worth as a percentage of disposable

personal income

850%

U.S. recessions

800

750

700

650

600

550

500

450

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2015

2020

the globe and mail, Source: Haver Analytics;

Rosenberg Research

U.S. households and non-profit organizations:

net worth as a percentage of disposable

personal income

850%

U.S. recessions

800

750

700

650

600

550

500

450

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2015

2020

the globe and mail, Source: Haver Analytics;

Rosenberg Research

U.S. households and non-profit organizations: net worth

as a percentage of disposable personal income

850%

U.S. recessions

800

750

700

650

600

550

500

450

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

2015

2020

the globe and mail, Source: Haver Analytics; Rosenberg Research

Who could ever have imagined that the most horrible epidemic in a century could have made so many people so rich? Does that make any sense to anyone?

Well, of course it does when the U.S. Federal Reserve, since the “Powell pivot” in 2019, eased policy to an extent that it de facto cut rates the equivalent of 865 basis points, 70 per cent of which came via the increasingly bloated central bank balance sheet. What happens now, with the movie reel about to be run in reverse?

Putting that 826-per-cent ratio into perspective, it has now far eclipsed the 669-per-cent housing bubble peak in 2007 and the 615-per-cent dot-com mania peak in 2000. We are in dangerous territory because the mean-reversion that lies ahead can be expected to be rather pernicious. Think of the decisions people made on the way up with this ratio, and what happens when it comes down.

Why inflation, commodities shocks are in the usual recipe for a recession

Houses in the suburbs seemed more affordable – then gas prices soared and commuting resumed

What keeps me up at night most is one number: 43 trillion. As in, the unprecedented US$43-trillion of equities, both directly and indirectly, that U.S. households own on their balance sheet. I should say “owned” and not “own,” because that was third-quarter data; that exposure grew to US$45-trillion in the fourth quarter. It has increased by 85 per cent since the end of 2018 and increased 252 per cent from a decade ago. Almost 40 per cent of the financial asset mix is now loaded up on stocks; the historical norm is 21.8 per cent.

And that is because the retail investor was lured by the pied pipers that populate Wall Street to believe in FOMO (fear of missing out), TINA (there is no alternative) and that the Fed has your back at all times. The household sector never rebalanced their portfolios in this cycle, as throwing caution to the wind also swept away that dirty 15-letter word – diversification.

Then tack on the super-inflated real estate valuation on the household balance sheet – topping US$42-trillion for the first time, up more than 15 per cent on a year-over-year basis, an increase that matches the bubble peak in 2007 when that valuation was pegged at US$25-trillion. The number of homeowner households since that 2007 housing bubble peak has expanded 10 per cent; but the valuation of residential real estate on the household balance sheet has absolutely exploded by 70 per cent.

The power of U.S. central bank policy lies in its ability to generate inflation in assets, which it can do when consumer inflation is below target. But the times, they are a-changin’. We had years (if not decades) of ultralow consumer inflation that co-existed with rampant asset inflation. The tables are soon to be turned. And what happens in this coming period of history is not a “wage-price” spiral but rather asset-price deflation, as the power of mean reversion takes hold, impairing consumer spending, wealth effects and confidence in the process. Even with lingering global supply restraints, this will sow the seeds of demand destruction, leading to a future of deflation.

David Rosenberg is founder of Rosenberg Research, and author of the daily economic report, Breakfast with Dave.

Be smart with your money. Get the latest investing insights delivered right to your inbox three times a week, with the Globe Investor newsletter. Sign up today.