The bad news for investors is that Canada will probably slip into a recession in the months ahead. The good news is that the recession may not feel like a recession at all.

One reason to think the downturn will be mild is Canada’s rapidly greying work force. An aging population is often seen as source of economic vulnerability, but at a time like now, when rising interest rates are chilling the economy, the country’s swelling number of seniors can actually provide some much appreciated flexibility.

Think of it this way: An aging population means an enormous number of Canadians are on the brink of retirement. About 2.6 million Canadians are now between ages 60 and 64.

Even if economic growth grinds to a temporary halt, the impending exodus of many of these people from the labour force should continue to open up opportunities for younger workers.

“In 1981, there were 14 Canadians between the ages of 60 and 64 in full-time work for every 100 Canadians aged 20 to 24,” Stephen Gordon, an economist at Université Laval, tweeted recently. “Now there are 45. The unprecedented flows into retirement will blunt the effects of any slowdown in job creation.”

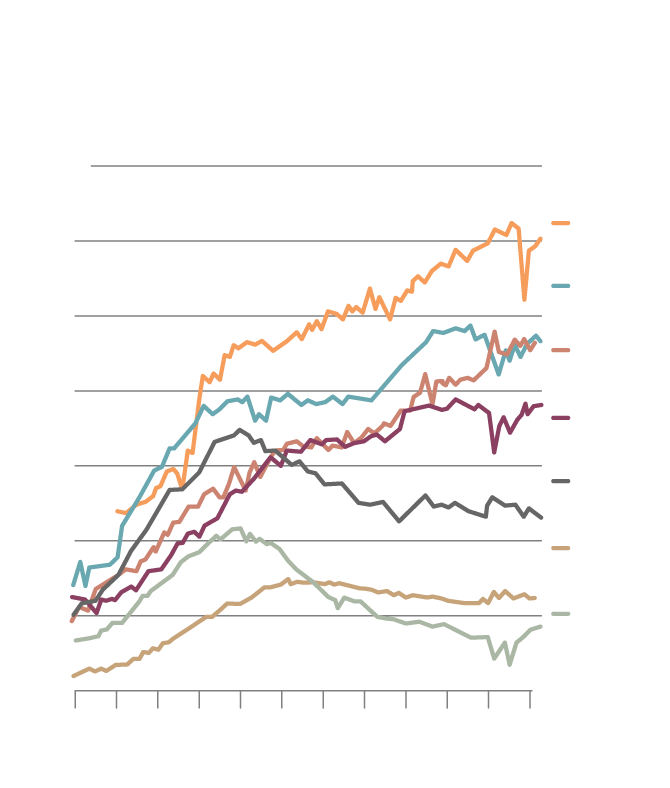

The rush to borrow

Canadians have gone heavily into debt over the past two decades –

but so have households in several other countries.

(Household debt-to-income ratios)

250%

Norway

225

Australia

200

Sweden

175

Canada

150

Britain

125

Eurozone

U.S.

100

75

‘00

‘02

‘04

‘06

‘08

‘10

‘12

‘14

‘16

‘18

‘20

‘22

the globe and mail, Source: deutsche bank

The rush to borrow

Canadians have gone heavily into debt over the past two decades –

but so have households in several other countries.

(Household debt-to-income ratios)

250%

Norway

225

Australia

200

Sweden

175

Canada

150

Britain

125

Eurozone

U.S.

100

75

‘00

‘02

‘04

‘06

‘08

‘10

‘12

‘14

‘16

‘18

‘20

‘22

the globe and mail, Source: deutsche bank

The rush to borrow

Canadians have gone heavily into debt over the past two decades – but so have households in several

other countries. (Household debt-to-income ratios)

250%

Norway

225

Australia

200

Sweden

175

Canada

150

Britain

125

Eurozone

U.S.

100

75

‘00

‘02

‘04

‘06

‘08

‘10

‘12

‘14

‘16

‘18

‘20

‘22

the globe and mail, Source: deutsche bank

Granted, even a mild recession will probably still carry a sting, especially for stock market investors.

Corporate profits soared in both Canada and the United States during the pandemic. Those lush profit margins are likely to come under pressure over the months ahead, as higher interest rates take their toll and tight job markets drive labour costs higher. Stock prices are vulnerable to a correction, especially if the Bank of Canada keeps interest rates high through 2023.

However, the real economy seems in sturdier shape than many critics acknowledge. Mr. Gordon points out that global prices for commodities are high and are likely to get another boost from China’s decision to drop its COVID-19 containment measures and reopen its economy. This bodes well for Canada’s commodity producers.

What about our well-known addiction to household debt? Canadians have gone heavily into hock, primarily to buy real estate. They have accumulated a near-record $1.83 in credit market debt for every dollar of household disposable income.

Robin Winkler, a Deutsche Bank analyst, warns that the cost of servicing that debt is likely to rise dramatically over the year ahead as higher interest rates ripple through economies. He sees Canada and Sweden as the two advanced countries most exposed to potential housing downturns.

That is a concern – but demographics offer reason to think the implications might not be as dramatic as some people fear.

One in five Canadian workers is now at least 55 years old, according to Statistics Canada. The working-age population has never been older on average and – as you might expect – leaving work behind has never been so popular. A record 307,000 people retired in the year ending last August, according to Statistics Canada.

The dwindling supply of experienced workers is reflected in one of the tightest job markets in memory. Unemployment in December stood at 5 per cent, just a hair above the record low of 4.9 per cent it reached this past summer. There are one million vacant jobs across the country.

Immigration is surging as Ottawa seeks to address the labour shortage. Canada is expected to welcome 465,000 immigrants this year, 485,000 in 2024 and 500,000 in 2025. That is nearly double the pace of a decade ago.

Put all these pieces together and it is easy to see why the system is stressed. It is more difficult, though, to see how a deep jobless downturn could manifest itself at a time when workers are already retiring in droves.

Yes, housing prices are likely to take a hit from rising borrowing costs, but with close to 1.5 million immigrants set to enter the country over the next three years, Canada seems to be suffering, if anything, from a structural shortage of housing.

For now, at least, the most likely scenario for the coming year seems to be one where the economy slows and maybe even shrinks for a couple of quarters, but avoids anything more dire.

What does this rather humdrum outlook mean for investors? For the most part, it suggests turning a deaf ear toward warnings of economic apocalypse. It means sticking to the boring basics of a balanced portfolio and waiting to see if a downturn later in the year exposes any attractive buying opportunities.

Looking further out, Canada’s aging demographics also underline the case for solid dividend stocks. Nothing cheers aging investors more than the prospect of being able to collect reliable payouts every year from their portfolios. As Canadians age en masse, the appeal of dividend stocks is only going to grow.