This article was originally published in September, 2014. In the lead up to the Canadian International Autoshow, we will feature a number of cars that will be showcased in Toronto. The show runs Feb. 13 - 22 at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre.

Globe and Mail driving columnist Peter Cheney drove a $140,000 Tesla Model S from San Diego to Whistler. His 2,800-kilometre journey was a test of both the electric car and the future of transportation.

DAY 1: SAN DIEGO

First impression: The Tesla Model S is like nothing I’ve ever driven before. As I aim the nose toward Los Angeles and accelerate up to highway speed, the only sound is the rush of high-speed air over the car. It reminds me of flying a glider – the noise and vibration of internal combustion are gone, replaced with an intoxicating whoosh.

I’ve tried several electric cars before, but they all felt like glorified golf carts. Not the Tesla. It’s blindingly fast and relentlessly futuristic: On the dash is a giant display screen that gives the cockpit the feel of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner.

The Model S’s throttle response is instant. There are no gears, and zero hesitation as it builds rpm (revolutions per minute) – the Model S rockets forward in a wave of silent speed. The California coast is blurring past, a streak of blue and gold. Leaving internal combustion behind may not be as hard as I thought.

I stop to take some photos of the car in front of the La Jolla surf. The Tesla’s door handles automatically retract into the body as I walk away. When I return, they glide out to meet me, driven by hidden servomotors and an alien intelligence it will take some time to get used to.

Ahead of me is a trip of more than 2,800 kilometres in a car that can’t refill at a gas station.

DAY 1: HAWTHORNE, CALIF.

I’m rolling up to my first Tesla Supercharger, a fill-up station that pumps electricity instead of gasoline. The station is located inside the compound of SpaceX, a company that builds rockets, and the curved roof is covered with solar panels that will supply the power I’m about to zap into my car. (Tesla chief executive Elon Musk’s business interests also include SpaceX and energy-supplier SolarCity.)

It feels like I’ve been transported into the automotive future: I’m topping up the Tesla with power from the sun while teams of technicians bolt spacecraft together in the buildings around me.

And I got a history lesson on the way. The route to the Supercharger took me through an old Los Angeles suburb filled with car-related businesses from the postwar era – dank grease pits, mouldering carburetor repair shops and a junkyard stacked with rusting engine blocks. After this, the Supercharger station feels like a computer clean room – a spotless environment of polished concrete and white steel that conjures up the lair of a friendly Bond villain.

DAY 2: MULHOLLAND DRIVE, HOLLYWOOD

Although I mapped out my trip in a spreadsheet to make sure I could make it between charging stations, I decide to take a detour into the Hollywood Hills for a trip along Mulholland Drive. This is one of my favourite roads, twisting through the steep slopes above L.A. like a bobsled track. Mulholland has a long tradition of speed – Steve McQueen and James Dean used to wring out their Porsches up here.

The Tesla is great through the curves, with instant power and accurate steering. But I know my range is taking a serious hit with all the climbing and hard acceleration. Do I have enough battery power left to make it to the next charger? I navigate to the range-calculation screen to see what’s going on.

An orange line traces across the screen like an EKG chart. This shows my energy use and predicts how much range I have left. As I’ve learned, the numbers are based on a number of variables – headwinds, climbs, high speed and hard accelerations can kill a lot of range.

Some smart engineers obviously put a lot of time into writing the algorithms that track the energy going in and out of the Tesla’s massive battery. In a car like this, software is king.

DAY 3: SAN FRANCISCO

I spend a few hours shooting pictures and video on the steep hills that look out over the Bay and Alcatraz prison. I’ve travelled nearly 1,000 kilometres since leaving San Diego, but I’ve spent nothing on fuel. When you get a Model S, you also get a lifetime energy supply – Tesla lets you fill up your battery at their Supercharger stations for free.

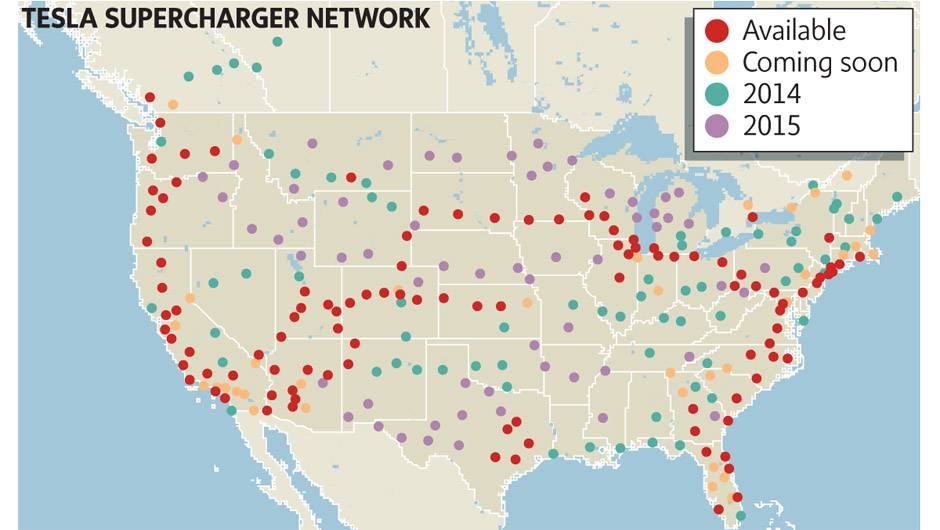

The only problem is that there are only 105 Supercharger stations in North America. Most of them are along the east and west coasts, which are the home to the highest concentrations of electric car buyers.

For the electric car industry, infrastructure is a chicken and egg conundrum: If there were more electric cars, the industry could afford to build more charge stations. And if there were more charge stations, more people would buy electric cars.

Driving the Model S has convinced me that electric power is superior to internal combustion. There are some caveats – batteries need to improve, for example, since their energy density is far lower than gasoline’s. But the rest of the car blows traditional technology away.

The motor resembles an oversized coffee can – it’s nestled in the tail end. There’s no oil to change, and no reciprocating parts to wear out. There’s also real joy in driving a car that produces zero emissions. Clean is good. Even though a lot of electricity is produced with carbon fuels, the electric car still represents a net gain – and clean power generation can change everything.

After a lifetime defined by oil sheiks, the Exxon Valdez spill and tailpipe emissions, I’m enjoying clean power. If there were a few thousand more Supercharger stations, I’d be ready to leave gasoline behind forever.

DAY 4: NORTH OF CORNING, CALIF.

I make my first big mistake. My destination today is Mt. Shasta, which is 173 kilometres away. Throwing caution to the wind, I disconnect the car from the Supercharger after just 16 minutes of charging. According to the car’s software, the battery is only about 60-per-cent charged, which will provide enough power for approximately 265 kilometres (a full charge will provide more than 430).

The past three days have given me a better feel for the car’s capabilities, and I’m fairly confident the 60-per-cent charge will be enough. But as I head north, I realize there’s a major grade ahead. My wife Googles the town of Mt. Shasta, and we learn that it’s more than 1,000 metres higher than where we are now. Now I’m starting to worry.

Range calculation is a complex process. Every car, whether it’s powered by electricity or gas, consumes power at a constantly varying rate. The main variables are weight, aerodynamic drag, grade and driving habits (a skilled driver can double a car’s fuel economy by minimizing throttle changes and driving at optimum speeds).

And the road can change everything. Over the next half hour, the Tesla’s predicted range plummets. My range margin shrinks. I feel like a bomber pilot heading back from a long mission, staring at the fuel gauges and praying that the airport appears before the engines quit. If I run out of power, there’s no way to get more.

Eighty kilometres into the drive, I turn around and head back to the Supercharger. Lesson learned.

DAY 5: PORTLAND, ORE.

The world of today isn’t always ready for the car of the future. I realize this when I wake up to a cruel surprise: The hotel has failed to charge the car.

I’d called ahead to find a hotel that had charging, and when I handed the car over to the valet, he assured me that the Model S would spend the night suckling at an outlet. But this morning, the car has exactly the same remaining range as it did last night – 80 kilometres. The next Supercharger on my route is 140 kilometres away.

The hotel gives us a room discount, buys us breakfast and plugs in the car again. Unfortunately, not all chargers are created equal. A Tesla Supercharger (such as the one that happens to be an unreachable 140 kilometres away to the north) could fill up the car in just more than half an hour. But the hotel charger can supply only a comparative trickle – 196 volts at 79 amps. Two hours later, there’s enough power in the battery to make it to the next Supercharger.

DAY 6: LANGLEY, B.C.

Despite yesterday’s hotel-charging hiccup, I love the Model S. I’ve had my doubts about electric cars in the past, but the Tesla is making me a convert. This isn’t just a great electric car. It’s a great car, period. My route has provided a comprehensive set of driving challenges – soaring mountain passes, downtown traffic, high-speed freeways and desert plains straight out of a cowboy movie.

The Tesla has handled it all with aplomb. It’s fast, quiet and eerily smooth. Accelerating at full power feels like being thrust forward by an electronic tsunami. And its great to drive a car that gets its power from the sky instead of a hole drilled in the ground.

DAY 7: WHISTLER, B.C.

I arrive here after stopping in Squamish, the final Supercharger on the West Coast route. By the time I got here, I had travelled more than 2,800 kilometres. Travelling through Vancouver this morning induced a strange sense of déjà vu. This is a city where I once worked as a Porsche-VW mechanic, buried deep in the world of internal combustion. I spent my days rebuilding engines, tracing down vacuum leaks and adjusting carburetors that wandered in and out of tune like fickle musical instruments.

Now I was passing through my former home in a car that rendered all this technology obsolete. In the Model S there are no pistons, no valves and no transmission. Instead, there is a battery, an electric motor and enough software to run a mission to Mars.

Despite my emotional connection to gas-powered cars, I realize that the age of internal combustion will come to an end. There are better ways to power cars than drilling crude oil out of the ground, shipping it halfway around the world, then burning it in an engine that spews a high percentage of its energy out the tailpipe in the form of heat.

The internal combustion engine is a complex device. Burning fuel drives pistons up and down inside an engine block that must be massive enough to contain the energy of heavy metal parts reciprocating at supersonic speeds. Air and atomized gasoline must be sucked into the engine through a set of valves, ignited with a perfectly timed spark, then blown out through another set of valves into the exhaust manifold.

The internal combustion process is hot, so you need an elaborate cooling system. It’s also noisy, which necessitates a set of mufflers. Friction is also a problem – without oil and an intricate network of passages that routes it through the engine, the moving parts would overheat and lock themselves together in a violent mechanical cataclysm (this sometimes happens anyway).

And then comes the overarching problem of speed range – internal combustion engines produce their power in a relatively narrow band (typically 1500 to 5000 rpm) You need a transmission that lets the engine stay within its limits as the car travels through a wide range of speeds. (Transmissions are even more complicated than engines, and when they go out of whack, the bill will not be small.)

All this mechanical complication has created an enduring industry – the repair business that once employed me. Changing dirty oil and rebalancing VW crankshafts paid my way through university. I apprenticed with German master mechanics who taught me to adjust valves, hone cylinders and plane cylinder heads so they didn’t leak.

Driving the electric Tesla makes me realize there’s a better way. The Tesla’s motor is packed in the tail near the rear wheels – it’s a small, barrel-shaped device that produces over 400 horsepower. Because of its vast rpm range and flat torque curve, no transmission is required. When you decelerate, the motor turns into a generator, pumping power back into the battery.

With the Tesla, there are no tune-ups, oil changes or cylinder-head overhauls. There are no coolant flushes or fan-belt replacements. It’s a mechanic’s nightmare. The oil companies hate it. But it’s a driver’s dream come true.

Electric car technology isn’t perfect. At the moment, the biggest obstacles to widespread adoption are battery technology (gasoline holds more energy a pound than batteries can) and infrastructure (there are a lot more gas stations than recharge points). But as history has shown, superior technologies have a way of prevailing in the long run. Some day we will look back on the gas-powered car in the same way we look back on horses, typewriters and steamships.

Will electric cars such as the Tesla Model S become the new transportation paradigm? Here’s hoping.