Anna Carroca casually strolls into action as a loud, piercing bell rings throughout the beige marble halls of a four-storey office town in downtown Toronto.

She walks into a green, cream-and-gold elevator cab, looks up at the panel for the requested floor, closes the cage door, grasps a black lever and pushes it to the left, and the elevator shoots toward the sky.

Jordan Chittley/The Globe and Mail

"Left is going up and right is going down," Carroca says, as we soar up the elevator shaft. "It has a brake, and you have full power to stop as if you were driving a car."

After 14 years at the elevator controls, Carroca makes it look easy. She jokes with tenants and rarely misses floors. If the operator doesn't stop in the right spot, he or she may have to readjust or force a passenger to step up or down into the cab. She won't let me operate it because there is a risk of damaging the elevator.

Self-driving cars Take a drive in a 108-year-old manually controlled elevator in Toronto

2:02

Most elevators were manually operated before the Second World War. Today, this one, built in 1908 at the Ontario Heritage Centre at 10 Adelaide St. E., is one of a few remaining in Toronto. Others are at the Goodenham (Flatiron) building, the Masonic Temple and the Gladstone Hotel.

"It's a very rare and vanishing type," says Romas Bubelis, architect with the Ontario Heritage Trust. "The visceral feeling you have as the air rushes by as you move up through the elevator shaft and being dependent on the elevator operator's hand … is anything but a dead automatic experience."

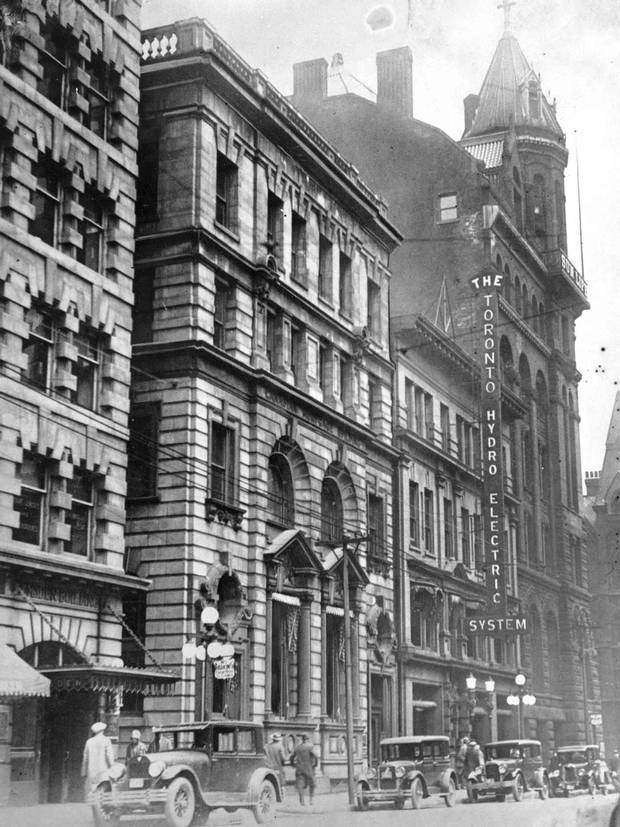

The historic Birkbeck building at 10 Adelaide Street East in Toronto in the 1930s

Ontario Heritage Trust

In the middle of the 19th century, Elisha Otis invented a game-changing safety mechanism that prevented an elevator from falling even if its cable broke, says Rob Isabelle, CEO of KJA, an elevator-consulting firm. By the turn of the 20th century, electric, manually operated elevators were commonplace in New York and were being installed in Toronto buildings.

"Most buildings into the 1950s had people waiting there to take you," says Lee Gray, professor of architectural history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and author of a book about the history of elevators. "Until we get to the 1950s there is a recognition the elevator needs a driver … You couldn't get by without an operator because you or I couldn't drive the car. I tried to do it once and missed by six inches."

In the early 1950s, push-button elevators were introduced en masse. Building owners could save money on operators and automated elevators increased efficiency and capacity. But there was a problem – people hated them.

"We have clear stories of people walking into elevators and walking right back out," Gray says. "Passengers were saying, 'I don't want to drive this thing, where is the operator?'"

Many people didn't feel comfortable giving up control to a machine, where all they had to do was push a button.

The call bell on a manually controlled elevator built in 1908 at 10 Adelaide Street East in Toronto.

Jordan Chittley/The Globe and Mail

It took most of that decade for people to become comfortable pushing the button on their own – and the elevator is a vehicle that only goes up and down attached to wires in a shaft.

"Like any new technology, people got used to it very quickly and now we don't even think about it," Bubelis says.

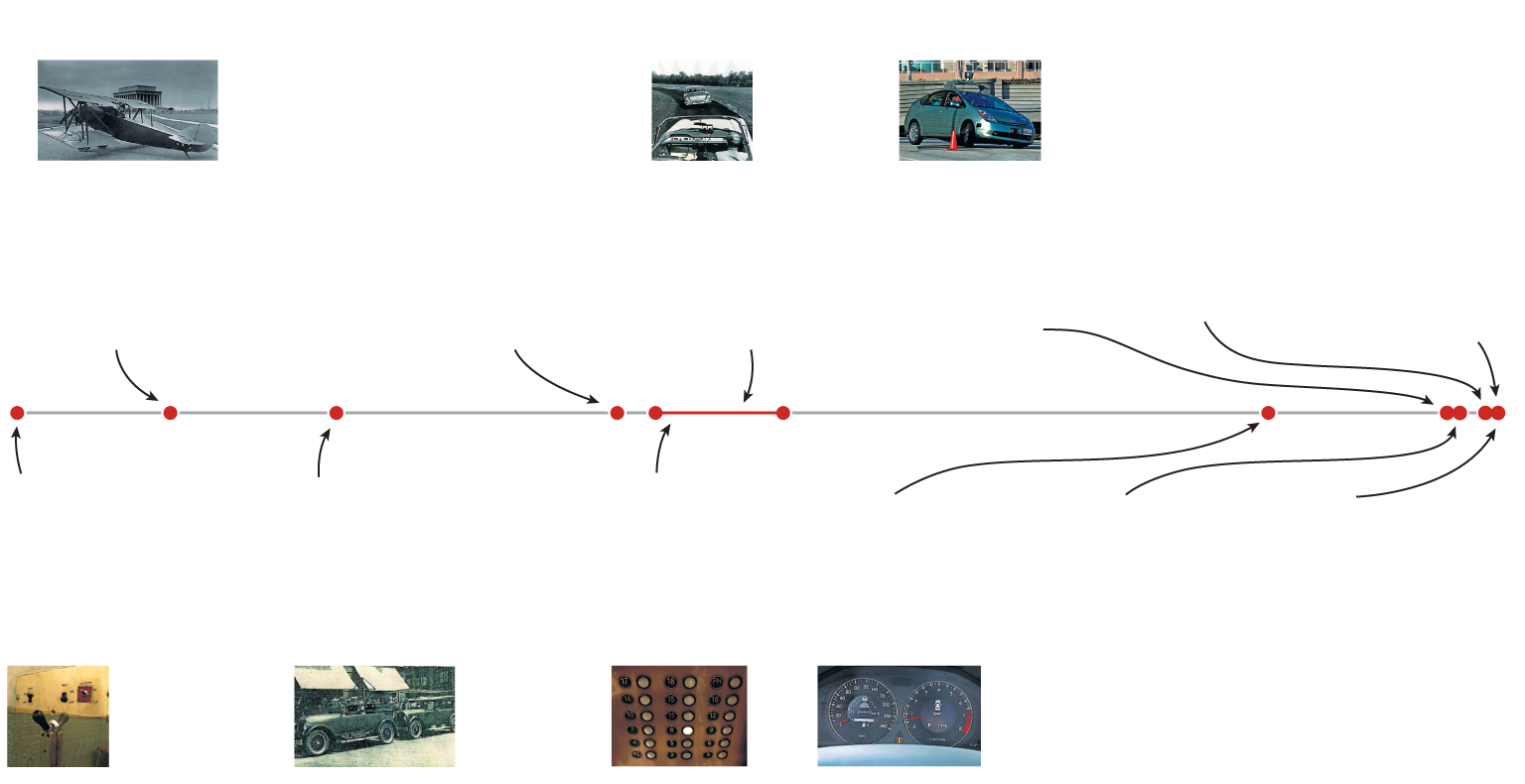

A history of the computer taking control

1912

First aircraft autopilot

developed

by Sperry Corporation

Around 1900

Completely automated

push-button elevators

available in small

apartments

1925

Houdina Radio

Control demonstrates

a radio-controlled car

operated by a

following car

1947

U.S. Air Force C-54

makes a transatlantic

flight, including takeoff

and landing completely

under the control of

autopilot

1950s

Automatic push-

button elevators

introduced en masse

1950s

GM and RCA test

vehicles on automated

highways using radio

controls

1998

Mercedes-Benz, Toyota

and Mitsubishi begin

offering adaptive

cruise control

2012

Google car passes

Nevada driving test

on 22 km route in

Las Vegas

2013

Mercedes-Benz

S-Class goes 100 km

on highways and

streets in Germany

2015

Audi A7s drive from San

Francisco to Las Vegas

2016

Uber and

nuTonomy begin

testing self-driving

taxis in Pittsburgh

and Singapore

2016

An Otto autonomous

transport truck drives

about 200 km to

make a beer delivery

in Colorado

A history of the computer taking control

1912

First aircraft

autopilot

developed

by Sperry

Corporation

1947

U.S. Air Force C-54

makes a transatlantic

flight, including

takeoff and landing

completely under the

control of autopilot

1950s

GM and RCA

test vehicles on

automated

highways using

radio controls

2012

Google car

passes Nevada

driving test on

22 km route in

Las Vegas

2015

Audi A7s

drive from

San Francisco

to Las Vegas

2016

Uber and

nuTonomy begin

testing self-driving

taxis in Pittsburgh

and Singapore

Around 1900

Completely

automated

push-button

elevators

available in small

apartments

1925

Houdina Radio

Control

demonstrates a

radio-controlled

car operated by

a following car

1950s

Automatic

push-button

elevators

introduced

en masse

1998

Mercedes-Benz,

Toyota and

Mitsubishi

begin offering

adaptive cruise

control

2013

Mercedes-Benz

S-Class goes 100

km on highways

and streets in

Germany

2016

An Otto

autonomous

transport truck

drives about 200

km to make a

beer delivery in

Colorado

A history of the computer taking control

Around 1900

Completely automated push-button

elevators available in small

apartments

1912

First aircraft autopilot developed

by Sperry Corporation

1925

Houdina Radio Control

demonstrates a radio-controlled

car operated by a following car

1947

U.S. Air Force C-54 makes a

transatlantic flight, including takeoff

and landing completely under the

control of autopilot

1950s

Automatic push-button

elevators introduced en masse

1950s

GM and RCA test vehicles

on automated highways

using radio controls

1998

Mercedes-Benz, Toyota and

Mitsubishi begin offering

adaptive cruise control

2012

Google car passes Nevada driving

test on 22 km route in Las Vegas

2013

Mercedes-Benz S-Class goes

100 km on highways and

streets in Germany

2015

Audi A7s drive from San

Francisco to Las Vegas

2016

Uber and nuTonomy begin

testing self-driving taxis in

Pittsburgh and Singapore

2016

An Otto autonomous transport

truck drives about 200 km to make

a beer delivery in Colorado

A history of the computer taking control

1912

First aircraft

autopilot

developed

by Sperry

Corporation

1947

U.S. Air Force C-54 makes

a transatlantic flight,

including takeoff and

landing completely under

the control of autopilot

1950s

GM and RCA

test vehicles on

automated

highways using

radio controls

2012

Google car

passes Nevada

driving test on

22 km route in

Las Vegas

2015

Audi A7s

drive from

San Francisco

to Las Vegas

2016

Uber and

nuTonomy begin

testing self-driving

taxis in Pittsburgh

and Singapore

Around 1900

Completely

automated

push-button

elevators available

in small apartments

1925

Houdina Radio

Control demonstrates

a radio-controlled car

operated by a

following car

1950s

Automatic

push-button

elevators

introduced

en masse

1998

Mercedes-Benz,

Toyota and

Mitsubishi begin

offering adaptive

cruise control

2013

Mercedes-Benz

S-Class goes 100

km on highways

and streets in

Germany

2016

An Otto autonomous

transport truck drives

about 200 km to

make a beer delivery

in Colorado

Autopilot

Captain Rob Johnson settles into his seat for a short flight from Toronto to Montreal. We aren't actually on a plane, but in a flight simulator in Mississauga, for Johnson to demonstrate how the autopilot system works.

He's looking at small, out-of-date screens, pushing buttons and turning small knobs. There are hundreds of them.

Capt. Rob Johnson sits in the pilot’s seat in a simulator at uFly in Mississauga, Ont.

Jordan Chittley/The Globe and Mail

"Once you lift off and fly the aircraft off the runway, gear is coming up, engage the automation, you can leave it [autopilot] in all the way until you disconnect for the final approach," says Johnson, who has been piloting aircraft for 45 years – including fighter jets and on 15-hour flights on Boeing 777s. "Some [pilots] leave it in until 300 or 400 feet above the runway."

About a minute after the rubber leaves the tarmac, Johnson hits one button, double checks some settings and then calmly removes his hands from the yoke. Blink, and you'd miss the computer taking control.

Self-Driving Cars How autopilot works and how it has changed flying

2:19

Johnson says pilots use autopilot 99 per cent of the time, and it can be used at many airports to land. But the system is only as good as the information input by the pilot. Autopilot allows pilots to focus on other issues such as navigating around approaching weather.

Prior to autopilot, flying was a grueling, dangerous experience. It was cold, windy and insanely loud – plus oil flew everywhere and the pilot had to constantly pull the plane to the left to compensate for the rotary engine. Constant attention was required to keep the plane on a straight course.

"The sheer physical fatigue that came from flying could quickly wear a man down, something not easy to understand for those of us who fly cosseted in the passenger cabin of a jet liner," Lee Kennett wrote in his 1991 book, The First Air War.

In 1912, Sperry Corp. developed the first autopilot system. It connected a gyroscopic heading indicator and attitude indicator to hydraulically operate elevators and rudders (the devices that move the plane up, down and side to side). It allowed the plane to fly straight and level on a compass course with little attention from the pilot. Inventor Lawrence Sperry showed it off in 1914 by flying past onlookers in Paris with his hands up in the air and off the controls.

"Over Ohio the other day, a big tri-motored Ford plowed through the air on its way to Washington, D.C. Four men leaned back at ease in the passenger cabin. Yet the pilot's compartment was empty. A metal airman, scarcely larger than an automobile battery, was holding the stick," begins a February 1930 article in Popular Science Monthly. "The sensitiveness of the robot in responding to movements of the plane is said to be superior to that of the average human pilot."

Aviation historian Keith Hyde says pilots were initially skeptical of autopilot and wary of turning over control, but technology improved over decades.

"Today, a pilot, even though he has to go through the courses … doesn't have much to do [while flying]," Hyde says.

The cockpit of a Boeing 777 flight simulator at uFly in Mississagua, Ont.

uFly

As we approach the landing strip in Montreal, a pleasant voice announces how many feet we are above the ground. Johnson monitors the screens and keeps his hands close to the controls, but doesn't touch them. The plane lands smoothly, but a little to the left, so Johnson disengages the system and drives it back to centre.

So why do we still need pilots?

To make the decisions, Johnson says.

"You program bad information and it will give you bad results," he says. "The pilot in command is ultimately responsible for the safety of the aircraft … Somebody has to mind the store."

104 years after the first autopilot, the system can do a lot, but it can't take responsibility.

This is the first article in a seven-part multimedia series on self-driving cars that examines the past, the current technology and what the future may hold.