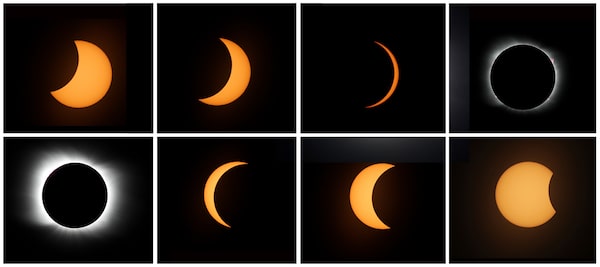

A total solar eclipse is more than just the moon covering the sun; it's a multi-phase spectacle from first contact, to the shadow bands, and, finally, totality.Natacha Pisarenko/The Canadian Press

It’s not just because they are rare that total eclipses of the sun are so special. They are also downright weird.

Blocking the sun is easy. You can do it with your hat. But when a 3,475-kilometre-wide ball of rock, a.k.a. the moon, does it for you, you get something that is much more than shade.

Various chroniclers have tried to capture what that experience is like. Among the most vivid descriptions from centuries past is one by Greek historian Leo the Deacon, who was a student living in Constantinople when he saw a total eclipse there in the year 968.

“One could see the disk of the sun dark and unlighted, and a dim and faint gleam, like a delicate headband, illuminating the edge of the disk all the way around.” Leo wrote.

Today those words survive as the first unambiguous description of the solar corona, a wispy sheath of ionized particles that can be seen only when the sun’s brilliant surface is entirely obscured by the moon.

The corona takes centre stage while the total eclipse is underway, but it’s not the only thing to look at. The challenge is things start to happen fast as totality approaches. Some eclipse goers pop on headphones to play a self-recording message in sync with the duration of the eclipse that reminds them to look and do certain things at the right time.

Whether or not you go to such lengths here’s a short list of phenomena to help you get the most out of this Monday’s event.

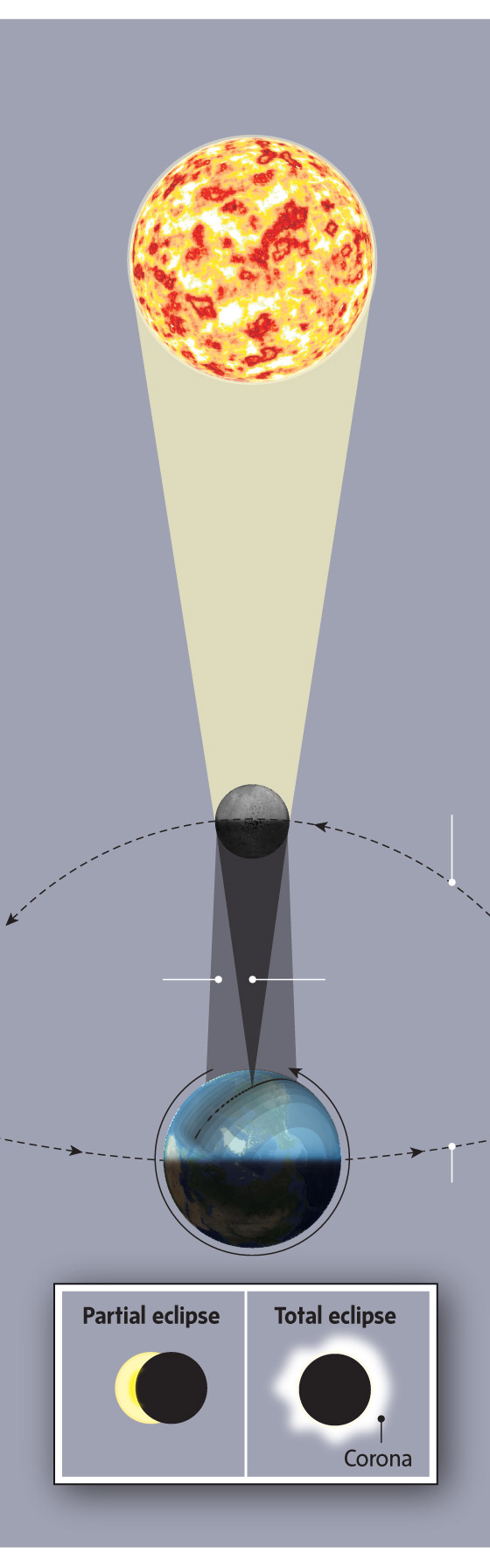

Moonshadows: The celestial geometry

behind a total solar eclipse

Sun

Moon

Moon’s

orbit

Partial eclipse

(penumbra)

Total eclipse

(umbra)

Earth

Earth’s

orbit

Partial eclipse

Total eclipse

Corona

*Diagram is not to scale.

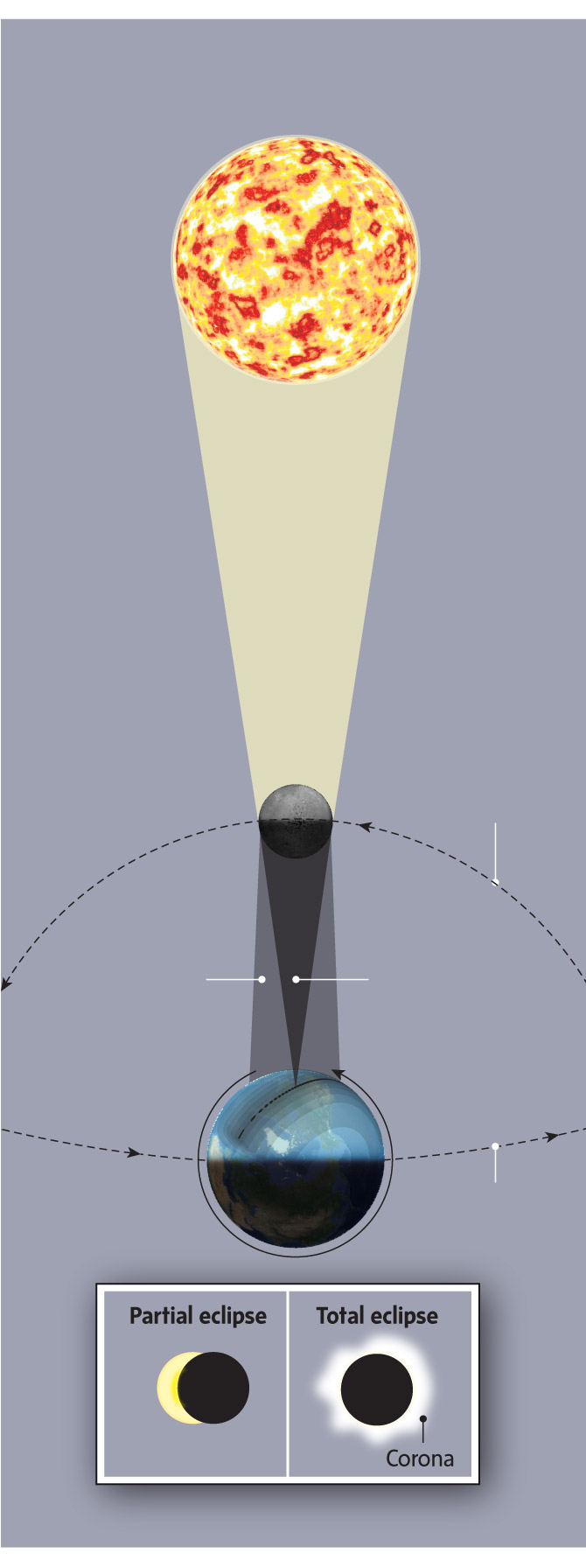

Moonshadows: The celestial geometry

behind a total solar eclipse

Sun

Moon

Moon’s

orbit

Partial eclipse

(penumbra)

Total eclipse

(umbra)

Earth

Earth’s

orbit

Partial eclipse

Total eclipse

Corona

*Diagram is not to scale.

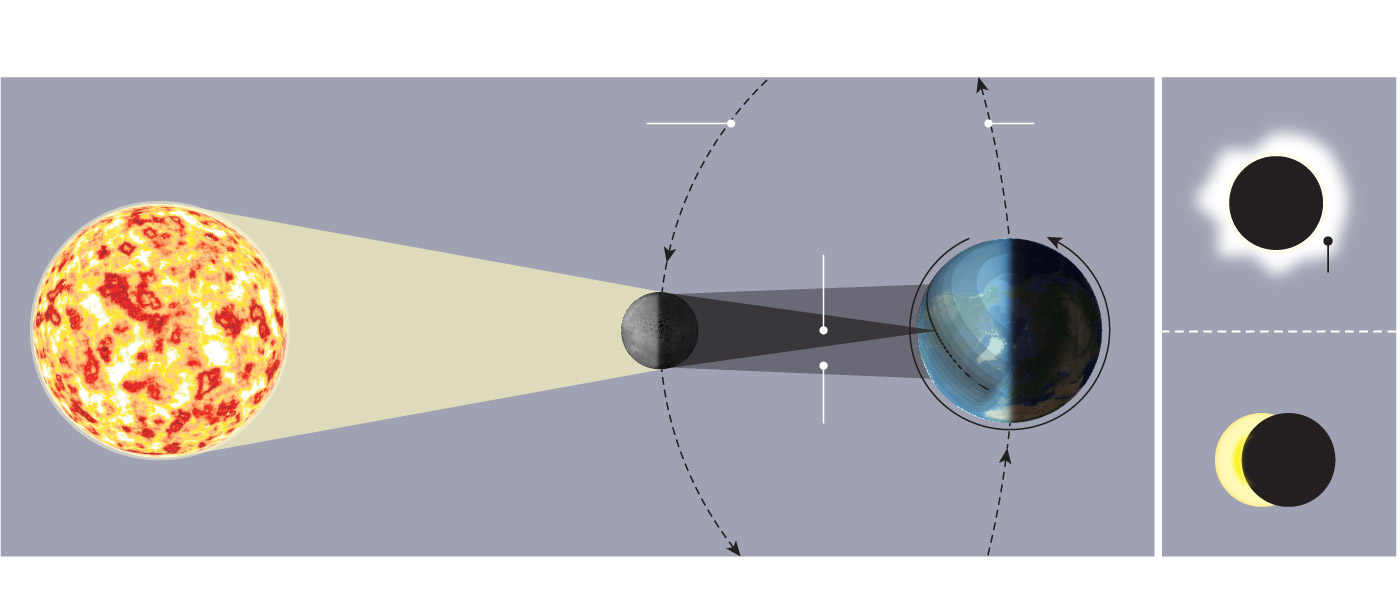

Moonshadows: The celestial geometry behind a total solar eclipse

Total eclipse

Earth’s

orbit

Moon’s

orbit

Total eclipse

(umbra)

Corona

Sun

Moon

Earth

Partial eclipse

Partial eclipse

(penumbra)

*Diagram is not to scale.

Umbra and penumbra

The moon has two shadows. The penumbra is the outer portion that spread out and can blanket a large fraction of the Earth. Anyone inside it will get a partial eclipse. Within it sits the umbra, the moon’s narrow, inner shadow where sunlight is entirely absent. Wherever the umbra touches Earth, it’s possible – briefly – to witness a total eclipse. The journey the umbra takes across oceans and continents is called the path of totality. The duration of the total eclipse is always longest toward the centre line of the path, in this case up to three minutes and 44 seconds long for some Canadian locations.

First contact

This is the moment when the leading edge of the moon first starts to cover the sun at the onset of the partial eclipse. It is a minuscule change, but for those in the path of totality, a harbinger of the spectacle to come.

A crescent sun

About one hour into the partial eclipse things will definitely start to feel different. By this time the shape of the sun will have changed from a circle with a bite in it to a crescent. Once the sun is about 90 per cent obscured a general dimming of the surroundings will be apparent and the temperature will begin to drop. Birds may react as though nightfall is approaching. Anything that casts a shadow with a small hole or narrow gap in it, including leaves and branches on trees, will project crescent-shaped images onto the ground. Shadows will sharpen at the edges and sunlight will seem more like theatre lighting from a bright but tiny spotlight. (Places that are just outside the path of totality will also experience this.)

Shadow bands

Just before totality begins, observers may notice an undulating pattern of light and dark stripes moving along the ground. These “shadow bands” are analogous to the ripples at the bottom of a swimming pool, but more subtle. They are caused by atmospheric turbulence refracting the narrowing rays of sunlight. You can use a white or light coloured drop cloth spread out on the ground to improve your odds of seeing this.

Baily’s beads

As the crescent sun becomes a hair-thin arc, mountain peaks along the jagged edge of the moon will pierce it in multiple places, turning it into a luminous string of beads. This effect, named after 19th century English astronomer Francis Baily, is typically only seen through a telescope or binoculars appropriately outfitted for safe viewing of the sun.

Corona

Once the total eclipse has begun, the sun’s corona will appear as a white sheen around the moon’s black silhouette during the total eclipse. The corona has a brush-like appearance shaped by the sun’s magnetic field which varies from year to year. No special protection is required to view the corona as long as the sun is entirely hidden from view.

Solar prominences

Bursts of hot plasma may be erupting along the edges of the sun during the eclipse. If they are large enough they can appear as stationary points of bright red light just beyond the moon’s dark rim. Telescopes and binoculars are generally better at revealing these, often in spectacular detail.

Planets and stars

The sky can go twilight-dark during a total eclipse. It’s at this point that it is often possible to see some of the brighter planets of our solar system during the day. The brightest will be Venus, which will be below and to the right of the sun during Monday’s total eclipse. Jupiter is next brightest and should appear on the opposite side, with about twice the separation.

Diamond ring

Photographers often try to catch the first of glint of light as the sun emerges from behind the moon. If you see it, it’s time to look away immediately to protect your eyes and watch the remainder of the partial eclipse with appropriate protection. But you’ll be left with the split-second memory of a glowing corona and a brilliant flare at one side – a celestial diamond ring that says it’s time to cheer and perhaps pop the Champagne. Congratulations! You’ve just seen a total eclipse!