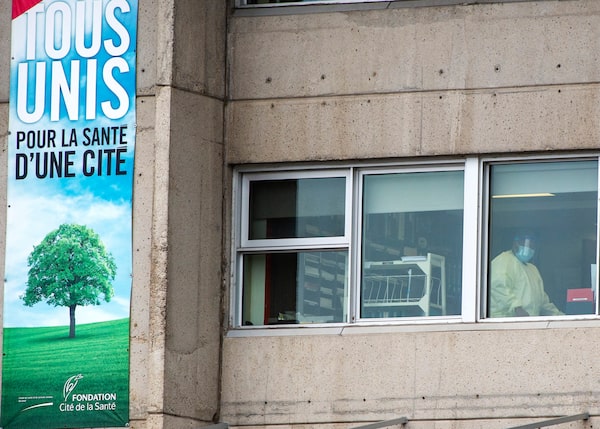

A health-care worker brings supplies into the Centre d'hebergement Sainte-Dorothee on April 7, 2020 in Laval Que.The Canadian Press

At the Sainte-Dorothée long-term care home north of Montreal, once the most lethal pandemic hot spot in Canada, orderlies no longer work part time, procedural masks are not under lock any more and coaches remind staff and caregivers of the proper way to use protective equipment.

These new practices stand in sharp contrast with the chaos of a year ago, when COVID-19 hit Canada. In a province that suffered the highest death toll in nursing homes in the country, Sainte-Dorothée was the deadliest of the nursing homes. Within its six floors in the suburb of Laval, 108 residents died.

But since the pandemic returned in a second wave last fall, no one has died at Sainte-Dorothée and only one of its current 193 residents got infected.

Tracking Canada’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout plans: A continuing guide

Canada pre-purchased millions of doses of seven different vaccine types, and Health Canada has approved four so far for the various provincial and territorial rollouts. All the drugs are fully effective in preventing serious illness and death, though some may do more than others to stop any symptomatic illness at all (which is where the efficacy rates cited below come in).

- Also known as: Comirnaty

- Approved on: Dec. 9, 2020

- Efficacy rate: 95 per cent with both doses in patients 16 and older, and 100 per cent in 12- to 15-year-olds

- Traits: Must be stored at -70 C, requiring specialized ultracold freezers. It is a new type of mRNA-based vaccine that gives the body a sample of the virus’s DNA to teach immune systems how to fight it. Health Canada has authorized it for use in people as young as 12.

- Also known as: SpikeVax

- Approved on: Dec. 23, 2020

- Efficacy rate: 94 per cent with both doses in patients 18 and older, and 100 per cent in 12- to 17-year-olds

- Traits: Like Pfizer’s vaccine, this one is mRNA-based, but it can be stored at -20 C. It’s approved for use in Canada for ages 12 and up.

- Also known as: Vaxzevria

- Approved on: Feb. 26, 2021

- Efficacy rate: 62 per cent two weeks after the second dose

- Traits: This comes in two versions approved for Canadian use, the kind made in Europe and the same drug made by a different process in India (where it is called Covishield). The National Advisory Committee on Immunization’s latest guidance is that its okay for people 30 and older to get it if they can’t or don’t want to wait for an mRNA vaccine, but to guard against the risk of a rare blood-clotting disorder, all provinces have stopped giving first doses of AstraZeneca.

- Also known as: Janssen

- Approved on: March 5, 2021

- Efficacy rate: 66 per cent two weeks after the single dose

- Traits: Unlike the other vaccines, this one comes in a single injection. NACI says it should be offered to Canadians 30 and older, but Health Canada paused distribution of the drug for now as it investigates inspection concerns at a Maryland facility where the active ingredient was made.

How many vaccine doses do I get?

All vaccines except Johnson & Johnson’s require two doses, though even for double-dose drugs, research suggests the first shots may give fairly strong protection. This has led health agencies to focus on getting first shots to as many people as possible, then delaying boosters by up to four months. To see how many doses your province or territory has administered so far, check our vaccine tracker for the latest numbers.

How Quebec’s long-term care homes became hotbeds for the COVID-19 pandemic

This critical transformation did not occur by happenstance. From changing the way it trains and hires personnel to quarantining new residents and relocating those who get sick, Sainte-Dorothée and its local health board exemplify the steps Quebec has taken to blunt the second wave’s impact.

According to a report released this month by the National Institute on Ageing, the second wave was deadlier for seniors in congregated settings in Ontario and Western provinces, but less lethal in Quebec. The report said the pandemic killed 4,902 LTC and retirement-home residents in Quebec last spring, while during the second wave 2,814 died as of Feb. 15.

“Quebec, which had the worst performance of any province during the first wave, has done far better than provinces like Alberta, B.C., Manitoba, Ontario and Saskatchewan, whose LTC and retirement homes experienced much worse outcomes during their second waves,” the report said.

Sainte-Dorothée was a relatively well-run public LTC, according to past inspections. However, it descended into chaos during the first wave, with 211 of its 253 residents getting the virus, in addition to 173 employees.

And having since admitted more than 100 new residents, the home couldn’t count on group immunity from survivors already exposed to the virus.

“One of the lessons we learned from the first wave is that a living environment has to turn quickly into a medical-care setting when COVID appears,” said Geneviève Goudreault, acting assistant executive director of the local health authority, CISSS Laval.

A review commissioned by the Health Department detailed a series of shortcomings at Sainte-Dorothée last year: employees with flu-like symptoms were not initially tested, staffers worked simultaneously at several places, masks were under lock, only a curtain separated infected patients from a testing area.

As the virus thinned the ranks of the staff, they were replaced by makeshift teams of unprepared personnel.

Like other local health boards, CISSS Laval now has a special mobile team of physicians and clinicians who can lend a hand when there is an outbreak.

Sainte-Dorothée gave all orderlies full-time positions with benefits.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

Sainte-Dorothée has dedicated Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) specialists who conduct audits and train staff. “They are our eyes and ears,” Ms. Goudreault said.

Quebec’s first-wave troubles were compounded by its decision to off-load hospital patients to LTC homes, out of fear that intensive-care wards would be swamped by COVID-19 cases. Instead, the move overloaded LTC homes just as the virus hit them.

CISSS Laval has now reversed that dynamic, with residents being moved out of nursing homes when they test positive, said Julie Rodrigue, a co-ordinator at Sainte-Dorothée.

Only one Sainte-Dorothée resident tested positive during the second wave. That person was transferred to a “red zone” set up at a hockey rink to quarantine infected LTC residents who don’t need to be admitted to hospital.

Before being admitted to Sainte-Dorothée, new residents have to test negative, then get quarantined as an extra precaution. That two-week isolation takes place in a buffer area set up so that Alzheimer’s patients, who are prone to wandering, can move freely and safely.

For legal reasons, staff cannot be compelled to be screened for the virus or vaccinated. However, Ms. Rodrigue said, 85 per cent get tested weekly and 64 per cent have been inoculated.

A key part of Quebec’s preparation for the second wave was an emergency program to hire 10,000 new orderlies. So far, 8,000 have been recruited and another 1,000 are in training, Quebec Premier François Legault said Tuesday.

Sainte-Dorothée went a step further, giving all orderlies full-time positions with benefits. In the past, up to 80 per cent were part-timers with no sick days, said the head of their union local, Marjolaine Aubé. “So there was a lot of personnel moving around to work a full day … they’d show up even if they were sick because they couldn’t afford to miss a day.”

She said all the changes have made a difference but warned of long-term challenges to retain the new employees.

The deaths at Sainte-Dorothée are being investigated at a coroner’s public inquiry.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

The Legault government promised to improve the orderlies’ pay when it launched its recruiting drive last summer. The training program advertised that the position paid $49,000 annually, roughly equal to a $26 hourly rate. But once on the job, the new staffers found their wage was actually about $21 an hour. To get to $26, they had to earn various bonuses by working nights and weekends, or in a red zone with infected residents.

Those bonuses are only paid during the pandemic and aren’t factored when calculating pensions, Ms. Aubé said. “That’s a bogus $26 an hour … a lot of people were disillusioned.”

She said the new orderlies have stayed on the job because their contracts stipulate that they need to work in LTC homes for at least a year, otherwise they have to reimburse the $9,120 bursary they received for their training.

Another labour issue is the shortage of nurses, which couldn’t be solved as readily as the lack of orderlies. “There’s a shortage of nurses across the province. You can’t become a nurse in three weeks,” Ms. Rodrigue said.

The deaths at Sainte-Dorothée and other Quebec LTCs with high death tolls are being investigated at a coroner’s public inquiry. Hearings resume Monday, with Sainte-Dorothée being studied starting on June 7.

Meanwhile, the steps taken in Quebec haven’t gone unnoticed in Ontario.

Testifying before Ontario’s inquiry into long-term care homes, infectious-diseases specialist Allison McGeer, a member of the province’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, underlined the decision by Premier Doug Ford’s government not to spend more to prepare LTC residents for the second wave.

“Quebec … put infection-control people in place, they hired a large number of additional staff. We chose not to do that in Ontario,” Dr. McGeer said.

Also appearing before the inquiry, Samir Sinha, director of geriatrics at Toronto’s University Health Network, praised Quebec’s move to set up IPAC teams and train more orderlies.

“These are two concrete things that I believe could have been adequately done over the summer [in Ontario],” he testified. “And for everybody who says they couldn’t be, I just say, look at la belle province next door. And you can see they really addressed those two issues.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.