Members of Lord Strathcona's Horse, A Squadron, fill sandbags to reinforce a dike in Princeton, B.C., on Nov. 27. When an 'atmospheric river' of rain hit two weeks earlier, Princeton's dike along the Tulameen was breached in two places and the town of 3,000 suffered devastating floods.Caillum Smith/The Globe and Mail

Shirley and Ron Klassen had never before shied away from floods at their small hobby farm in Arnold, B.C. But on Nov. 15, as firetrucks ripped through the town, and the Klassens watched the water rise around them, they realized that this time, it was different. Packing up their dogs, the couple left behind a slew of farm animals and headed for higher ground.

As Ms. Klassen speaks, anger sets in as she talks about the catastrophe’s predictability.

“The technical engineers, not that long ago, said the dikes were not stable,” she said. “And nothing was done.”

Indeed, reports predicting dike failures in B.C. go back decades. One of the most recent, a report for the Fraser Basin Council from March, 2021, concluded that “most of the dikes in the province do not fully meet provincial standards” and would likely breach even during relatively weak storms. Many haven’t been properly maintained and suffer from known defects. The fragility of the infrastructure was highlighted even earlier; a 2013 report commissioned by the province estimated over two-thirds of them were in “poor to fair” condition, while 18 per cent were labelled “unacceptable.”

They’re certainly inadequate in the face of a rapidly changing climate, and as torrential rain continued to pound B.C. this week, and Abbottsford remains under evacuation orders, the state of the province’s dikes has become an increasingly urgent concern.

A person walks a dog in an Abbotsford residential neighbourhood on Dec. 1 as flooded farmland lies in the distance.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

All told, B.C.’s 1,100 km of dikes protect 160,000 hectares, equivalent to slightly less than a third of Prince Edward Island. They afforded British Columbians confidence when settling what otherwise might have been considered risky land. Floodplains in the Fraser Valley and Metro Vancouver are now home to hundreds of thousands of people and buildings (homes, schools, hospitals and the like) as well as crucial transportation corridors, collectively worth billions of dollars.

Flying over the Abbotsford area, Tamsin Lyle, principal of flood management consulting firm Ebbwater, observed a breach she guessed to be 60 to 80 metres across. Murky waters flowed onto the Sumas Prairie (a plain sandwiched between Sumas Mountain and Vedder Mountain about six kilometres across), filling a former lake drained nearly a century ago to make way for agricultural land. Dozens and dozens of square kilometres of that farmland lay underwater, with farmhouses, outbuildings and some elevated roads punctuating the sea of brown.

In Merritt, B.C., a city of more than 7,000, the Coldwater River inundated swaths of the downtown area and residential neighbourhoods. In Princeton, B.C., a town of fewer than 3,000 souls, the Tulameen River punched two holes in a dike about 600 metres apart.

Interviewed nine days after the catastrophe, a provincial official couldn’t provide a tally of how many dikes failed and where. In a statement, the provincial government said local governments “are still assessing the consequences.”

As are Shirley and Ron Klassen. “Heads need to roll,” said Ms. Klassen. “I don’t know whose heads.”

What happened when Abbotsford’s dikes failed

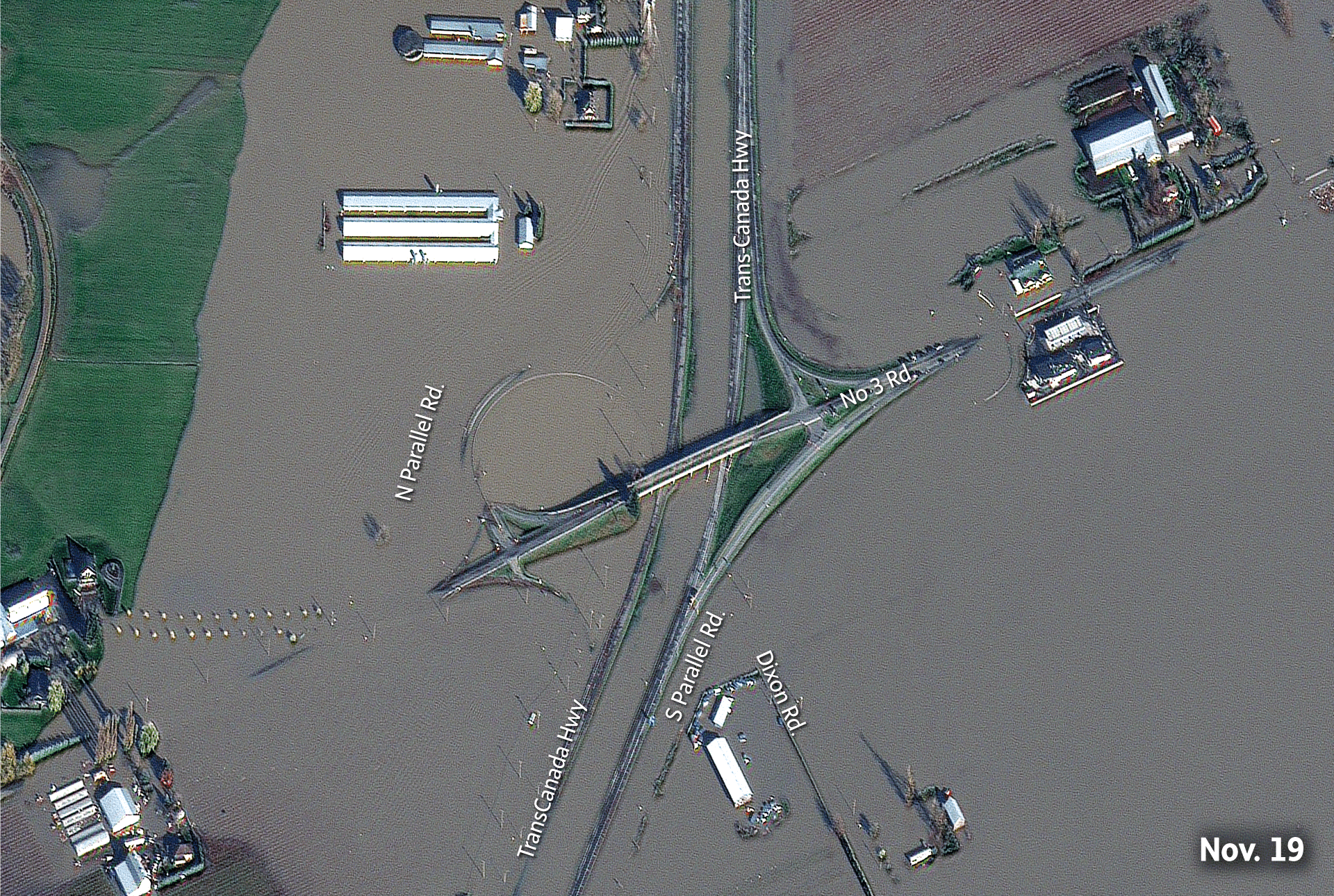

When some of the dikes protecting Abbotsford gave way, the areas highlighted in the map below – the agricultural heartland of the Fraser Valley – were under water. Under the map are two before-after comparisons of satellite footage showing the damage to areas near the Trans-Canada Highway.

Legend

B.C.

Alta.

Extent of

flooding

on Nov. 17

Abbotsford

Dikes

Fraser River

Chilliwack

River

11

No 3 Rd.

No 4 Rd.

No 5 Rd.

Abbotsford

Campbell Rd.

Highway 1

Vye Rd.

0

2

KM

U.S.

B.C.

Alta.

Legend

Extent of flooding

on Nov. 17

Abbotsford

Dikes

Fraser River

Chilliwack

River

11

No 3 Rd.

No 4 Rd.

No 5 Rd.

Abbotsford

Campbell Rd.

Highway 1

Vye Rd.

0

2

KM

U.S.

Mission

Fraser River

Chilliwack

River

Matsqui

Island

11

No 3 Rd.

No 4 Rd.

No 5 Rd.

B.C.

Alta.

Abbotsford

Campbell Rd.

Abbotsford

Highway 1

Legend

Extent of

flooding

on Nov. 17

Vye Rd.

2

0

Dikes

KM

U.S.

A history of failure

Those looking to assign blame, or simply understand, need to look back to decisions made decades ago.

B.C.’s berms were mostly built in fits and starts, following damaging floods. Diking began as early as the 1860s, but it wasn’t until after the Second World War that they got their first severe test. In 1948, the second-worst flood in B.C.’s history struck, which caused a few dikes to fail. About 2,000 homes were destroyed, and 16,000 residents evacuated.

In 1949, Ms. Lyle said, two “gentleman engineers” were dispatched from Ottawa to restore the public’s faith in the diking system. “They thought the way to do that would be to build it back fast,” she said. “They came up with a design standard within six months … the standard that we use to this day, in terms of the shape and size and the types of slopes.” Dikes were also built close to riverbanks, a decision that created serious problems down the road.

The province introduced a new provision in the 1970s: Henceforth, new dikes would need to be able to withstand a 1-in-200 year flood (that is, one that has a 0.5 per cent of occurring in any given year, the estimated probability of the 1894 flood.) This standard is roughly equivalent to one used in parts of the United States, but far less than in Holland and some other parts of Canada.

Dike crest elevations are a tough call under the best of circumstances. But according to Ms. Lyle, most communities lacked sufficient data on climate and water levels to make sound calculations. “They were looking at maybe 20 years of recorded water levels,” she said. “If they were built today, we would come up with a different number.”

Time is no kinder to dikes than it is to slapdash calculations. Particularly in the first couple of decades following construction, they settle – in extreme cases by as much as a metre. River deltas also tend to sink by millimetres a year as sediments compact. Many rivers gradually silt up, further reducing the margin of safety afforded by dike crests.

A Royal Canadian Air Force helicopter surveys the Fraser Valley on Nov. 21.Jennifer Gauthier/The Canadian Press via AP

Silting also shifts river currents, accelerating erosion where little existed before. Abbotsford has wrestled with that for decades along the Fraser River’s bank. The estimate for repairing a particularly large “erosion arc” perilously close to the Matsqui Dike, in 2014, was $2.8-million. A smaller one discovered last year rang in at $131,000.

Several years ago, the City hired a consultant to explore root causes. The conclusion was unsettling: Much of the south bank “is unstable and other erosion arcs could develop and potentially undermine the dike in the near future.”

Solutions included dredging (up to $10-million every two years), shoring up the banks with rock spurs ($4-million) or rock armouring (up to $20-million). All of those options, though, were cheaper than correcting the original sin by moving the dikes back.

But while the list of necessary upgrades grows ever longer, the plain truth is that many of B.C.’s dikes aren’t even properly maintained. A 2003 report by the B.C. government noted that, “unfortunately, due to general economics and personnel limitations,” necessary work gets done only some of the time.

That was, and remains, an understatement. More than a decade later, the province hired engineering firm Northwest Hydraulic Consultants to review its own records and data to build a database evaluating dikes’ condition. That initiative found that just 4 per cent of the province’s dikes could contain a 1-in-200 year flood.

But by then, so much development had taken place behind the dikes that officials realized even the old 1-in-200 year standard mightn’t suffice. “Preliminary quantitative risk analyses indicate that much higher standards may be justified for protection of densely populated urban areas,” another report noted, this one published in 2014.

Flooding in the Sumas Prairie area of Abbotsford on Nov. 17.DON MACKINNON/AFP via Getty Images

Abbotsford understood its exposure all too well. A year ago, engineering firm Kerr Wood Leidal Associates Ltd. produced a report on its behalf examining flood risks in the Sumas Prairie. To prepare that report, the firm’s engineers waded through no fewer than 22 previous studies produced between 1991 and 2018.

The risks were stated clearly on its first page: “During extreme flood events, floodwaters in the Sumas Prairie have the potential to overtop and breach the dike system protecting the Old Sumas Lake Bottom.” Previous studies had concluded the dike was vulnerable “because it was constructed without controlled spillways and inadequate structural protection.”

Here, again, costs threw up a roadblock. The same report noted that “multiple” solutions had been suggested in “numerous studies” since 1990, including floodproofing individual properties, constructing new floodways and spillways. Estimates ranged as high as $580-million.

Such costs need to be weighed against the consequences of doing nothing. And those, too, were mounting rapidly. Yet another report warned that if the province’s worst flood (in 1894) revisited the Lower Mainland, the estimated damages might be as high as $23-billion.

Dikes “make people feel safe, and they feel attracted to the area behind it,” said Ms. Lyle. “And then we develop in those areas, even though we shouldn’t. We often develop poorly, we’re not even making people raise their homes up because we have a dike that’s protecting them.”

She continued: “The other thing about dikes is that they only work until they fail. And when they fail, they fail catastrophically.”

People in Abbotsford watch floodwaters crossing the Canada-U.S. border on Nov. 29. Flooding and breached dikes on the Nooksack River in Washington state are a recurring flood risk to the lower-lying areas on the Canadian side.Jonathan Hayward/The Canadian Press

Catastrophic failure

Shirley and Ron Klassen had endured flooding before. In November, 1990, just a couple of years after they built their farmhouse in Arnold, the nearby Nooksack River in Washington State spilled over its banks. But on Nov. 15th. ), as Ms. Klassen watched water creep across the street toward the farm, she could see this time might be different.

At 6 a.m. the following morning, fire trucks drove up the street in front of the Klassens’ home, sirens blaring, urging everyone to evacuate. Surrounding properties flooded but the Klassen’s 4-hectare farm, Prairie Wynd Stable, remained above water. Neighbours sent horses, cows, goats and chickens to the Klassens’ for safety, joining the Klassen’s dogs and five horses.

“I put a stake at the edge of the water and waited an hour or two, and it was still coming, that water,” she said. “It was four feet high over Arnold Road by 2 o’clock.”

This time really was different: Nearby dikes suffered multiple breaches. With the roads disappearing, the couple, in their 70s, finally gave in, grabbed the dogs and drove up a small gravel road to higher ground.

Precisely how the dikes failed isn’t known. There are several possibilities. The most basic, known as overtopping, occurs when water spills over the dike crest. Fast-moving water quickly cuts through the dike, causing sections to fail.

Dikes can fail well before overtopping occurs. They’re seldom impervious: water gradually penetrates their soils. A saturated dike can slump. Water can also seep through channels (such as those made by beavers and other burrowing animals), leading to collapse.

Flood debris lies along the Tulameen River in Princeton on Nov. 27.Caillum Smith/The Globe and Mail

On Nov. 15, Clint Lee was up for work at 6:10 a.m. He looked out the window and discovered their 5-hectare property, 11 kilometres east of Princeton, was under water. The Similkameen River was now lapping at the door. He suspected a nearby dike, designed to keep the Similkameen River from crossing the Crowsnest Highway, had failed. “We had just enough time to grab the animals, our phones and get out,” Ann Lee recalled. “The driveway was eroding under the truck as we were leaving.”

The Lees returned home to clean up. Their home was dry, but their barn was under water and the fences were down. They sent a well water sample for testing, to determine if it was safe to drink. They tried, and failed, to get anyone out to assess or repair the dike. When the rains returned on Sunday, Nov. 28 and the river began to rise again, they packed up their animals and evacuated once more.

The Lees have lived on the property for 22 years and have long watched the dike warily. Ten years ago, it was supplemented with sandbags. “It wasn’t sufficient, it was just a band aid,” said Ms. Lee. “Last year [the water] was six inches from coming over the highway.”

DIKE INFRASTRUCTURE AND FLOODING AROUND MERRITT

Legend

B.C.

Alta.

Extent of

flooding

on Nov. 16

Merritt

Dikes

0

450

Nicola River

m

5A

Merritt

Houston St.

Coldwater

River

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; NATURAL RESOURCES CANADA; GOVERNMENT OF B.C.

DIKE INFRASTRUCTURE AND FLOODING AROUND MERRITT

B.C.

Alta.

Legend

Merritt

Extent of flooding

on Nov. 16

Dikes

0

450

Nicola River

m

Princeton-Kamloops Hwy

Merritt

Houston St.

Coldwater

River

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; NATURAL RESOURCES CANADA; GOVERNMENT OF B.C.

DIKE INFRASTRUCTURE AND FLOODING AROUND MERRITT

Nicola River

8

Princeton-Kamloops Hwy

Merritt

B.C.

Alta.

Merritt

Houston St.

Legend

Coldwater

River

Extent of

flooding

on Nov. 16

0

450

Dikes

m

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; NATURAL RESOURCES CANADA; GOVERNMENT OF B.C.

Merritt is protected by dikes made of sand and gravel along both banks of the Coldwater River, as well as along segments of the smaller Nicola River. Greg Lowis, public information officer for the City of Merritt, said the Coldwater rarely floods: The smaller Nicola, in contrast, frequently causes some overland flooding.

As the November storm approached, city officials consulted flood maps depicting which parts of town which would be inundated by a 1-in-200 year flood. The dikes held for the first couple of hours, Mr. Lowis said. But the Coldwater’s flow rate reached three times its previous record, producing forces so great it cut a new channel through backyards and homes.

The worst floods in Merritt’s history had arrived. Real-time flooding data generated by Natural Resources Canada depict extensive flooding throughout downtown Merritt, suggesting its dikes had been completely overwhelmed.

“We’re now thinking it was more like a 1-in-400, 1-in-500, 1-in-1,000 year event,” said Mr. Lowis. “Our dikes simply were never built with that in mind.”

Crews repair the Sumas dike on Nov. 21. Fixing the dike was a priority for authorities in the time between the mid-November floods and later waves of storms that would bring more rain to the Fraser Valley.City of Abbotsford

Turning point?

For the moment, B.C. officials are preoccupied with triage. In a briefing on Thursday, B.C.’s Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth said the province is focused on ensuring the repaired Sumas dike in Abbotsford will hold as more storms hit B.C.’s south coast. But experience elsewhere has shown that major floods present a rare, narrow window of opportunity for major reforms.

The Flood Hazard Statutes Amendment Act of 2003 has long been contentious. It enabled B.C.’s provincial government to transfer power over flooding issues to local governments. Flooding experts say the transfer greatly reduced the B.C. government’s accountability for managing flood risks and accelerated deterioration of its capacity to do so: Staffing levels, which had already been declining, plummeted thereafter.

In a report published in May which examined the fallout, Ebbwater argued that the 2003 download created “a mismatch in responsibility and accountability.” Municipalities face perverse incentives: They should prevent floodplain development, but are rewarded with property tax revenues when they don’t. Higher levels of government, meanwhile, pick up most of the recovery tab after damaging floods.

B.C.’s dikes are owned and maintained by more than 100 diking authorities, and they were not all created equal. Surrey (population 580,000) has approximately 100 kilometres of dikes running either side of the Serpentine and Nickomekl Rivers, both of which empty into Boundary Bay. Some regard the municipality as the gold standard: It has an engineering department supported by contractors. Through the Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund, the federal government recently earmarked $76-million to help Surrey (as well as Delta and Semiahmoo First Nation) implement a flood adaptation strategy, which includes upgrading dikes.

Matt Osler, a city engineer specializing in climate adaptation, said the 2003 downloading has largely served the city well, providing improved autonomy to manage flood risks “in the best way for our community.” He added that the city doesn’t rely entirely on dikes: It has also restricted development of its floodplains, for instance.

A truck crosses a flooded Old Yale Road in Surrey on Nov. 14.Shane MacKichan/The Globe and Mail

Smaller communities can’t match Surrey’s resources. In a 2018 interview, Neil Peters, a water resources engineer who once served as B.C.’s inspector of dikes, pointed to Nicomen Island, just east of Mission, where dikes protect Highway 7 and a major rail line.

“That diking system is 35 kilometres long, and it’s being run by volunteers, farmers, property owners,” he said. “They’re just local guys who know how to keep the pumps going … those dikes are gonna be among the first to give way if we get any significant flooding.”

Other dikes have no owners at all. According to a report published a year ago by consultancies Kerr Wood Leidal and Ebbwater, there are 105 “orphaned” structures, typically built in response to an emergency with little oversight or engineering expertise. Maintenance is generally poor if not entirely absent. The consultants couldn’t even find all of them; three missing dikes were presumed “destroyed by the watercourse.”

The Union of B.C. Municipalities has long opposed the 2003 download. Jen Ford, a councillor from Whistler and a UBCM vice-president, said local governments inherited a system of flood control – including dikes – without the means to maintain them.

Official pronouncements suggest change might be imminent. On Nov. 26, Premier John Horgan declared the 2003 downloading a “bad call.” Mr. Farnworth said the massive rebuilding effort now required in B.C. will have to be completed with climate change in mind – and that included ensuring dikes are built to higher standards. Municipal Affairs Minister Josie Osborne has said both the provincial and federal governments are committed to helping pay for the clean up and reconstruction.

“Nobody expects communities to do this alone,” she said, asserting that the provincial and federal governments will “be there as partners with financial support for rebuilding community infrastructure.”

But just how much money will be available for this is unclear. The costs associated with upgrading dikes after a prolonged period of neglect are unknown, but they are likely to be staggering. The aggregate estimated cost to mend and upgrade orphan dikes alone is $865 million – and that’s a small fraction of the province’s total dike infrastructure.

There are other options. Recognizing the limits of large engineering works, flood mitigation specialists increasingly recommend “non-structural” measures aimed at reducing flood damages rather than controlling water. These include a wide variety of tactics including restoring natural wetlands to store more water, or preventing high-value development of floodplains in favour of parkland that would be far cheaper to repair following flooding than, say, a major subdivision. But those, too, can be very expensive.

Asked whether the November, 2021, floods represent a turning point, the City of Surrey’s Mr. Osler said he’s optimistic the province will direct more resources into flood management. Ms. Lyle, though, remains skeptical.

The province last endured flooding on this scale in 1990, she said. “That was only 30 years ago, and nothing really changed,” she added. “The politicians get up and talk about it for as long as it takes to keep the public’s interest. And then they just go back to doing the same thing they were doing before.”

B.C. floods: More from The Globe and Mail

The Decibel

On The Globe’s news podcast, environment reporter Kathryn Blaze Baum explains how B.C.’s mid-November rainstorms became so destructive. She also wrote an explainer with Matthew McClearn about how the “atmospheric river” effect brought so much water to B.C.

More coverage

B.C. flood updates: Storm forecasts, road closings and more

Floodwater flowing from Washington State to B.C. exposes vulnerabilities along border

Farmers devastated by B.C. floods return to gut-wrenching scenes

Residents of Merritt, B.C., return home after evacuation to find destruction and sorrow