The Premier’s Office in Manitoba had the air of an abandoned bunker last month: shelves bare, personal effects hastily removed, dust motes dancing in the sunbeams. The only remnant of the previous tenant, Heather Stefanson, whose Progressive Conservatives held power in Manitoba for seven years, was a plain wooden clock and an abandoned houseplant.

New Democrat Wab Kinew, elected on Oct. 3, had moved just one item into the dark, oak-panelled office: a buffalo skull, a remnant of the sacred midsummer Sundance – and a reminder of the healing and renewal that led him to this office after a youth spent headed in the opposite direction.

Next door, a hodgepodge of Mr. Kinew’s suit jackets, spare ties, and framed art were piled in the office of his Principal Secretary, Emily Coutts. “He really needs to deal with that,” she murmured to no one in particular, as a pair of techies tried to get the phones working.

Ms. Coutts, 28, was, in that moment, fine-tuning a news release announcing that the board of the Manitoba Public Insurance Corporation was being fired en masse, an effort to get the Crown corporation’s 1,700 employees – on strike since August – back to work.

The new board would include the president of the Manitoba wing of the Canadian Union of Public Employees and an NDP MLA, signalling Labour’s renewed power in the province after seven years of strife with the outgoing Tories.

They had also just unveiled the country’s most diverse cabinet. For Deputy Premier, Mr. Kinew chose a 39-year-old Black, non-binary former psychiatric nurse, Uzoma Asagwara, who played basketball for Team Canada in their twenties. Two First Nations women were given key portfolios. In a neat bit of political theatre, Mr. Kinew appointed himself Minister of Indigenous Reconciliation, inverting the significance of a post once considered marginal.

The sense of hope that Mr. Kinew, 41, inspired in his supporters has much to do with a life trajectory unique in the history of major political candidates in this country.

Winning the premiership was the latest in a lifetime of dramatic transformations: from rapper to university vice-president, from activist to bestselling author, from criminal to statesman. Mr. Kinew insists that he isn’t running from any of it.

“I feel a reverence to the past. It’s important to face it – by being straight up and clear eyed,” Mr. Kinew said in his first sit-down interview since his victory.

“I was given the opportunity to have a second chance, and I smartened up. I made good on it. It’s a process – of continuing to make good on it.”

There are few places where the gaping inequity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians comes so clearly into focus as it does along the jagged, granite shores of Lake of the Woods, where Winnipeg’s gentry class spends its summers. The vast lake, with its sailing regattas, infinite blue bays and boozy yacht club dances, boasts some of the country’s most exclusive cottage country.

It is also where Mr. Kinew spent the first few years of his life, on the Ojibways of the Onigaming First Nation, one of more than a dozen Anishinaabe First Nations clustered along the lake’s craggy shores.

The median income on Onigaming, a colourful knot of prefab houses built on the sandy hills above Sabaskong Bay in Northwest Ontario, is $20,288. In Kenora, the regional hub – an hour’s drive north on Highway 71 – it is $86,000.

“It can be hard to see optimism here,” says Onigaming Chief Jeff Copenace. The community buried 32 members in the past two years, some 10 per cent of the population. Most were under 45; they died from suicide, alcoholism, and accidental overdose, says Mr. Copenace. “That’s why Wab’s victory was so meaningful here: It represents a light in the darkness.”

Mr. Kinew’s mother, Kathi Avery Kinew, the daughter of a Toronto ad executive, was an Indigenous policy analyst. His father, Tobasanakwut Kinew, an academic and a First Nations leader, was among those who helped launch the Indigenous civil rights movement in Canada in the 1960s. Mr. Kinew describes his mother as a foil to his father’s sharp edges: gentle and nurturing where his dad was gruff and impatient. Both were intensely political, says Mr. Kinew – “they raised me around the negotiating table, so to speak.”

By the time he was 3, Mr. Kinew was spending two days a week in Murray Sinclair’s living room in St. Andrew’s, north of Winnipeg, where the former judge who would later chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission ran an informal Anishinaabemowin language school for a half-dozen Anishinaabe kids.

Mr. Kinew wishes his mother, Kathi Avery Kinew, a happy birthday on election night.David Lipnowski/The Canadian Press

Before kindergarten, Mr. Kinew moved with his family – he has a younger sister, Shawonipinesiik, who is now an associate professor of art history at Harvard University and an older half-sister, Diane Kelly, a lawyer – to Winnipeg’s south end.

During summers on Onigaming, the elder Mr. Kinew piled his kids and grandkids into a fishing boat, chugging down the lake. He showed them petroglyphs and trap lines; he taught them to harvest wild rice and offer tobacco to thunderbirds when it rained.

“The teachings, the language, the land – it instilled a pride and a foundation in us,” says Mr. Kinew’s elder sister, Ms. Kelly, who later became a regional Grand Chief, like her father and two of their uncles. “When you’re raised like that, it’s hard for people to push you off your centre.”

But the elder Mr. Kinew had been deeply scarred by his time at St. Mary’s, a Catholic residential school in Kenora. As a parent, he could also be aloof, absent, angry, particularly following the death by suicide of Darryl, his eldest son from a previous marriage, when the young man was 19. Mr. Kinew’s anger became a malignant presence in the family home.

“When I did something wrong, I was yelled at for being stupid,” Mr. Kinew recalled in his memoir, The Reason You Walk. “When I got hurt and cried, I was yelled at for being weak. When I sat inside for too long, I was yelled at for being lazy.”

Mr. Kinew came to fear and hate his dad. He learned to bury his anger, the same way his father had.

In the late ‘90s, just before entering the University of Manitoba, where he studied economics, Mr. Kinew formed the conscious hip hop foursome Slangblossom, later joining the Dead Indians, a rap group. On weekends, he often travelled alone to Kenora to sweat with an Elder, and deepen his spiritual learning. He also began drinking heavily, shedding his straightedge persona. After a few beers, a meanness buried deep within him would emerge. For a time, he lost himself to fist fights, anger, addiction.

Mr. Kinew’s criminal past, which includes two arrests for assault, has been well documented. His father, by then a revered leader, was furious and disappointed when Mr. Kinew was picked up for refusing a breathalyzer following a police chase. But he surprised his son, showing him mercy, love and forgiveness. That summer, at the Sundance, the elder Mr. Kinew named his son a chief and gave him his war bonnet – the red-beaded, feathered headdress he wore to be sworn-in as premier almost 20 years later. More than any other inheritance, this was the greatest gift his father gave him, says Mr. Kinew: when he was broken, his dad lifted him from the depths, making him whole again.

Mr. Kinew had begun piercing at the Sundance as a teen, but at that point, hadn’t performed the ritual in two years. During a piercing, dancers have slits cut into their backs or chests; into the incisions go wooden pegs lashed to buffalo skulls. To show reverence by giving something of themselves to the Creator, they then pull the heavy skulls behind them, stretching the taut skin until finally the pegs tear through flesh and muscle, an agonizing, bloody release that can take hours. That summer, Mr. Kinew, whose chest is pocked with scars, pierced three times.

Back in Winnipeg, he threw himself into Alcoholics Anonymous, sometimes taking in three meetings a day. He worked out. He read widely. When he and his girlfriend April Spence had their first son, Dominik, the new father found work in warehouses and on construction sites to support his young family.

Mr. Kinew speaks at CBC headquarters in Toronto, when he was guest-hosting Q. He began working in broadcasting in the 2000s.Kevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail

In late 2005, Mr. Kinew wrote a letter to the editor in the Winnipeg Free Press, arguing in favour of Todd Bertuzzi’s controversial selection to Team Canada after the hockey player had ended another player’s career following an on-ice incident: “I am a young man with a criminal record and have felt the pain and frustration of losing out on jobs and opportunities because of it,” Mr. Kinew wrote. “I refuse to believe that at 23 years of age my life should be over because of mistakes I have made.”

This caught the eye of a producer at CBC Winnipeg’s morning radio show, and eventually led to a reporting gig. But while Mr. Kinew’s professional life was blossoming, his family life was coming undone. In 2007, shortly after the birth of their second son, Bezhigomiigwaan, he and April separated. The pain drove Mr. Kinew to consider suicide. He got through it by logging still more hours at the gym, and later came to national prominence as the host of the CBC TV series 8th Fire, an edgy, provocative exploration of Indigenous-settler relations.

It wasn’t until Mr. Kinew was 30 that his dad explained the depth of his pain, and what was done to him at residential school: the sexual and physical abuse, the depravity – a beating he received at age nine, on the day his father was buried. Mr. Kinew gathered his father, then in his 70s, in his arms. This was the first time they had embraced in this way, he realized.

As the elder Mr. Kinew finally grappled with his pain, his grief and anger began to fade; the barriers that kept him from truly loving his family came down. Mr. Kinew understood why his dad had screwed up as a parent. He forgave him.

In February of 2016, four years after his father’s death – and a year after declining an offer to run for the Grits federally – Mr. Kinew announced he would seek the NDP nomination in Fort Rouge, a safe NDP seat in central Winnipeg.

Asked why he had chosen mainstream politics instead of following his father into First Nations leadership, he said simply: “This path wasn’t open to my dad. He had tremendous potential and capability. I have the opportunity.”

In 2017, Mr. Kinew won the party’s leadership.

The crowning of the new party leader is supposed to be a moment of triumph. But there was no honeymoon for Mr. Kinew. He inherited a greatly diminished party that was riven by internal discord.

Two years later, the governing Tories easily won re-election. But Mr. Kinew had replaced the NDP’s old guard with a slate of new MLAs. The party added four seats, and Mr. Kinew proved he could run a disciplined campaign. His concession speech sounded more like a victory address. He left the stage to the tune of Curtis Mayfield’s Move On Up.

Mr. Kinew’s ambition – some call it impatience, others arrogance – have long annoyed rivals. Whatever the case, the ex-rapper’s best moments are often unscripted.

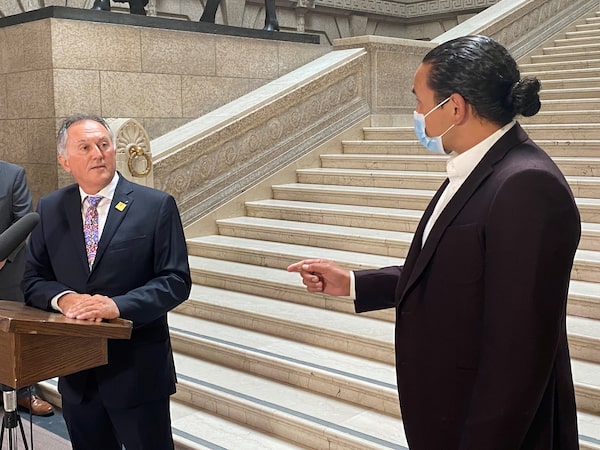

In 2019, Tory Alan Lagimodiere, freshly sworn in as minister of Indigenous reconciliation, told reporters gathered on the legislature’s marble staircase that residential schools had been founded with “good intentions.”

Before Mr. Lagimodiere could finish the thought, Mr. Kinew approached, momentarily hijacking the new minister’s inaugural news conference. He calmly explained why this was untrue.

Mr. Kinew confronts Alan Lagimodiere in July of 2021. The minister later apologized for saying the builders of the residential-school system meant to do good.Steve Lambert/The Canadian Press

That equanimity doesn’t mean Mr. Kinew is beyond delivering the occasional partisan kick in the teeth. Manitobans were reminded of Mr. Kinew’s intemperate side after a bizarre incident last April, when Mr. Kinew gripped Obby Khan, a Tory MLA, in a lengthy handshake at an event in the legislature’s second-floor rotunda, speaking into his ear.

Mr. Khan, a former offensive lineman with the Blue Bombers, accused Mr. Kinew of unleashing a profanity-laced tirade, then shoving him. Mr. Kinew acknowledged that he was irked by a speech given by the rising Conservative star, but said there was no swearing or shoving.

But tempering his anger, Mr. Kinew acknowledges, is still a work in progress: “Over the years, I’ve always tried to improve myself. When I look into the mirror, I try to focus on weaknesses – on being straight up about what I see, then trying to remedy the situation through consistency and effort.”

In the end, another incident, involving another man named Khan, says something else about the premier’s character.

In 2019, CBC Manitoba fired Ahmar Khan, a young TV reporter for leaking news that his bosses made him delete a tweet calling out Don Cherry’s racism. Mr. Kinew didn’t know the South Asian reporter. But he was familiar with what it feels like to try to change a large institution as a person of colour. He invited him for a coffee.

Mr. Khan had grown up poor, in a single-parent home in Surrey, B.C., he told The Globe. Trying to make it in journalism had been tough sledding. The job was everything to him. His firing left him in such a dark space he was thinking of suicide.

Mr. Kinew told Mr. Khan to keep fighting. He described how he and several colleagues pushed the CBC to adopt the term “survivors,” when referring to those who had been to residential school. “He listened,” Mr. Khan recalls. “He was kind. In times where you begin to lose hope, you really struggle. It meant a lot.”

The fall election felt like an existential struggle over what it means to be Manitoban. On one side, there was Tory Heather Stefanson’s hard-right vision that took aim at trans kids, and a pledge not to search a landfill for the remains of two murdered First Nations women. On the other was Mr. Kinew’s moderate, middle-of-the-road approach, and a belief that cultural, religious and sexual differences – as well as balanced budgets – are Manitoba’s strength.

Looming in the background, though left curiously unaddressed, was the spectre of history, of the yawning chasms that separate Indigenous from non-Indigenous Manitobans.

For a man with a tattoo spanning the length of his forearm reading “Live by the drum,” and its mate running down the opposite arm that says “Die by the drum,” Mr. Kinew fought a remarkably traditional campaign. He promised to “fix health care,” and opened most speeches with a hokey pun: “How do you do? I’m Wab Kinew.” He sold Manitobans on a series of pocketbook promises that might have been cherry-picked from a Conservative platform. He announced a pair of them – suspending the 14-cent provincial sales tax on gasoline and freezing Hydro rates – weeks before the Tory campaign launched, catching the opposition flat-footed.

In a pre-election speech, Mr. Kinew addressed his past transgressions head-on.

Mr. Kinew admits to having felt “pretty, pretty nervous,” ahead of the speech. He called Mr. Sinclair for advice.

“Show people that you’re not ashamed of your past, but you have learned from it,” the retired judge recalled telling him. “Tell them there will always be an opportunity for a second chance.”

That message gave the speech its compelling, redemptive thrust. And it deftly removed what, for years, had been a central focus of the Tory campaign: Mr. Kinew’s checkered past and the idea that his Indigeneity will make him soft on crime.

This time, “Manitoba didn’t buy into it,” says Lloyd Axworthy, the former foreign affairs minister who hired Mr. Kinew at the University of Winnipeg, when he served as its president. “People understood there was something bigger at stake.”

Mr. Kinew performs a pipe ceremony wearing his father's war bonnet.John Woods/The Canadian Press

The day after the vote, which gave Mr. Kinew’s NDP a majority government, the incoming Premier drove to Paradise, a plot of land on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, home to the Sicangu Lakota, where his Sundance family had gathered to honour him. It was the site of many watershed moments in his life, including his wedding to Anishinaabe physician Lisa Monkman, with whom he has a five-year-old son, Tobasanakwut. The little boy, who shares his late grandfather’s name, goes by Toba, a nickname for the province.

In the weeks since, the Manitoba Premier has announced two inquiries – one into a police headquarters scandal and another on the province’s pandemic response – and hinted at a coming shakeup at Manitoba Hydro. He apologized to the families of the slain women whose remains are believed to be in a landfill, for having their relatives treated as political footballs.

Six weeks after the election, it’s still “Wabamania” back on Onigaming, where the community recently held a pickerel fry to celebrate Mr. Kinew’s achievement, says Mr. Copenace. Mr. Kinew’s campaign signs are everywhere – outside the band office, at a stop sign, on the side of a home, along the road. Ontario highway workers removed them, but people keep putting them back up.

“Hopefully, this will mark a turning point for some of our young people – to become dreamers, to start thinking of a future, of college or university, or even about becoming the next Wab Kinew.”

But there is no blind optimism here, no ignorance of the unnervingly high stakes facing the new premier: “Being a leader can be terribly lonely,” says Mr. Copenace. “In his darkest moments, I hope Wab stays rooted in his teachings, in his medicines, in ceremony. He can rely on Onigaming – I hope he knows that.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly spelled the name of former CBC Manitoba reporter Ahmar Khan. This version has been updated.

Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Manitoba politics: More from The Globe

Tanya Talaga: Wab Kinew’s win in Manitoba suggests the lighting of the Anishinaabe eighth fire

Lloyd Axworthy: The Wab Kinew I know is going to change Canada

Mike McKinnon: Expect Wab Kinew’s government to carry the torch of Prairie pragmatism

By playing gutter politics, the Manitoba PCs deserved to lose

Nancy Macdonald

Nancy Macdonald