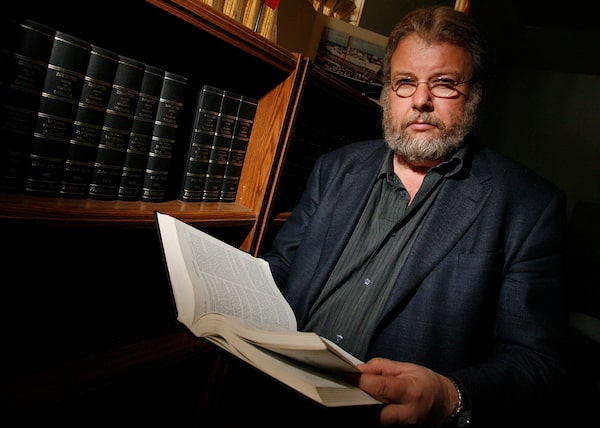

Bill Blaikie, MP for Transcona, in his Winnipeg constituency office on March 15, 2007.JOHN WOODS/The Canadian Press

Nearly everyone who speaks about Bill Blaikie talks, somehow, about bigness.

There was the towering intellectual and moral reputation he acquired over three decades representing Winnipeg for the NDP in the House of Commons, where even those who ferociously disagreed with him always listened when he spoke. He exerted a gravitational pull, so that people clustered around him at events and a compliment from him to a colleague on a job well done became a badge of honour.

There was a largeness of spirit that allowed him to be one of the most serious and thoughtful people on Parliament Hill, but also the one who would launch into a Robert Burns poem when the mood struck, and recite Address to a Haggis at his annual Burns suppers. He raised a brood of four kids and managed to feel close and present for them, despite a hefty job that demanded much.

His politics were expansive; his deep belief in social democratic values was undergirded by his faith as an ordained United Church minister, but Rev. Blaikie was a true believer who could be a clear-eyed pragmatist when the moment called for it. He never led the party that he embodied for decades, and the disappointment from the near-miss when he tried to win the leadership ran deep.

“Everyone liked Bill Blaikie,” says Don Boudria, who spent years jockeying with him as government House leader for Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government when Mr. Blaikie was House leader for the NDP.

There was the booming voice; bear hugs that were slightly terrifying if they caught you by surprise; his enormous love for the outdoors, the bagpipes and his family’s Scottish heritage; all of it, people will tell you, as big as the man himself – and that was big. It’s tempting to assume that his admirers mentally boosted his physical size to match their esteem for him, but he stood a full 6 feet 6 inches tall, so affectionate inflation seems unlikely.

It’s more like Bill Blaikie occupied an improbably large space in the world, and then built a life, reputation and career to match.

He died at his home in Winnipeg on Sept. 24 from kidney cancer at the age of 71, leaving his wife, Brenda; their children, Rebecca Blaikie, Jessica Blaikie-Buffie, Daniel Blaikie and Tessa Blaikie Whitecloud; and four grandsons to mourn him, along with countless political colleagues and opponents.

William Alexander Blaikie was born on June 19, 1951, in Winnipeg.Fred Chartrand/The Canadian Press

“After 30 years in Parliament, I can’t think of anyone from any party that speaks ill of Bill,” Pat Martin, his former caucus colleague, says. “It’s a measure of the respect people had for the way he conducted himself as an MP.”

William Alexander Blaikie was born on June 19, 1951, in Winnipeg. His father and grandfather worked for the Canadian National Railway, and Mr. Blaikie worked there as a student, before earning a bachelor’s degree in religious studies and philosophy from the University of Winnipeg and a master of divinity from Emmanuel College at the Toronto School of Theology. He was ordained as a United Church minister in 1978 and elected as a member of Parliament the following year, representing Winnipeg—Birds Hill (the riding was subsequently redrawn as Winnipeg—Transcona in 1988 and Elmwood—Transcona in 2004).

“He was an interesting contradiction, almost. He was a classic rumpled academic, but he never forgot where he came from either, which was a working-class railway family in Transcona,” says Mr. Martin, referencing the blue-collar suburb on Winnipeg’s east side originally established as home to the railway repair shops. “I like to think the House of Commons is still reverberating with his thunderous refrain he used to harp on: ‘Take the freight off the roads and put it back on the rails where it belongs!’”

In his faith and politics, Mr. Blaikie belonged to a Social Gospel tradition with deep roots in the NDP through predecessors like J.S. Woodsworth, Tommy Douglas and Stanley Knowles. In his 2011 memoir, The Blaikie Report: An Insider’s Look at Faith and Politics, Mr. Blaikie defined the Social Gospel as “the vision of all those who, out of their Christian faith, perceived and articulated the need for fundamental changes in the capitalist world view and in capitalism itself.” He was frustrated that as time went on, people only saw faith as belonging to the politics of the right, and that it often meant a smaller, meaner vision for the world than the Social Gospel fight for justice and inclusion.

His sprawling career – he was at one point the longest continuously serving MP, dean of the House by both longevity and reputation – covered seismic eras of Canadian politics. He helped to shape debate and legislation on the patriation of the Canadian Constitution, free trade and post-9/11 security measures, and he raised concerns about climate change and globalization decades before they became mainstream issues.

“I think he had more impact than he realized, because he really built up his credibility over many, many years,” says Bob Rae, his caucus colleague in the early years.

Mr. Blaikie was particularly proud of his role in shaping the Canada Health Act of 1984. Former Liberal Health Minister Monique Bégin described him in her memoirs as waging “guerrilla warfare” in order to force the federal government to put a stop to the extra billing and user fees that threatened to undermine medicare. In his own book, Mr. Blaikie recalled a parliamentary page handing him a note from Ms. Bégin, thanking him for holding her feet to the fire and encouraging him to keep at it so she would have leverage with her cabinet colleagues.

Mr. Blaikie was also a master of parliamentary procedural chess, which gave the NDP caucus some clout that its small numbers wouldn’t have been afforded otherwise. After the 2000 election, when the party was reduced to a whiff, Mr. Martin remembers Mr. Blaikie thundering in a convention speech, “‘We’re only 13, but we ride like a hundred!”

In 2002, when NDP Leader Alexa McDonough announced she was stepping down, Mr. Blaikie was the first to declare himself in the running to replace her; a month later, Jack Layton jumped in with the promise of renewing the party. Ed Broadbent, party leader over the first decade of Mr. Blaikie’s parliamentary career and a close friend, agonized over the decision before ultimately throwing his support behind Mr. Layton. “Bill was quite disappointed, to put it euphemistically,” he says.

Mr. Layton won on the first ballot, and the decisiveness of the loss was deeply bruising to Mr. Blaikie. He accepted Mr. Layton’s invitation to be deputy leader, but his rift with Mr. Broadbent lingered, until they finally grew close again over the past decade. “It was one of the great joys of my life that we did get back on track,” Mr. Broadbent says.

Mr. Blaikie left federal politics in 2008, after nearly 30 years on the opposition benches and stints as deputy speaker, House leader and parliamentary leader for the NDP and multiple critic roles. Manitoba Premier Gary Doer asked him shortly after to run provincially, and he served as minister of conservation and house leader in the government of Mr. Doer’s successor, Greg Selinger, before retiring for good in 2011.

Away from politics, his faith and Transcona Memorial United Church were his ballast, while the outdoors was his playground; paddling, camping and hiking were enormous components of Blaikie family life.

Bill Blaikie, who spent nearly 30 years as an MP, has died.Courtesy of the Family

Daniel Blaikie remembers one camping trip when he was about 11 years old, at a favourite spot in Whiteshell Provincial Park, which his dad treated “like his backyard.” It started out idyllic: camping on an island, with freshly caught fish for breakfast. But when they headed for home, the weather turned surly and the motor on their boat refused to start. Mr. Blaikie tried steering as the wind shoved them along, and it almost worked, but they ended up marooned against a false shoreline. This was the early 1990s, and Parliament had provided MPs with mobile phones in little carrying cases. Somehow, Mr. Blaikie found a signal and called home, where Rebecca (who would later serve as president of the NDP) answered. He told her to call a nearby resort, give their location and tell them they needed a rescue.

The wait was a couple of long, soggy hours. Hunched in the bow, Daniel was cold and uncomfortable, but his enduring memory was a deep, reassuring calm: Dad had a plan, he would get it sorted. “He was just unflappable in the face of all that, you know? I just remember not feeling at any time like things weren’t gonna work out,” Daniel says. “Because, you know, he was there.”

Decades after that camping trip, in 2015, Daniel would be elected for the NDP in his father’s old seat. The elder Mr. Blaikie brought along his bagpipes and piped his son into his victory parties.

After Bill Blaikie died on Sept. 24, when his body was transported out of his house, Daniel piped him out with Amazing Grace. “I was glad to be there to play the pipes as he left his house for the last time,” he says. “I think he would have wanted it that way.”