Illustration by Pui Yan Fong

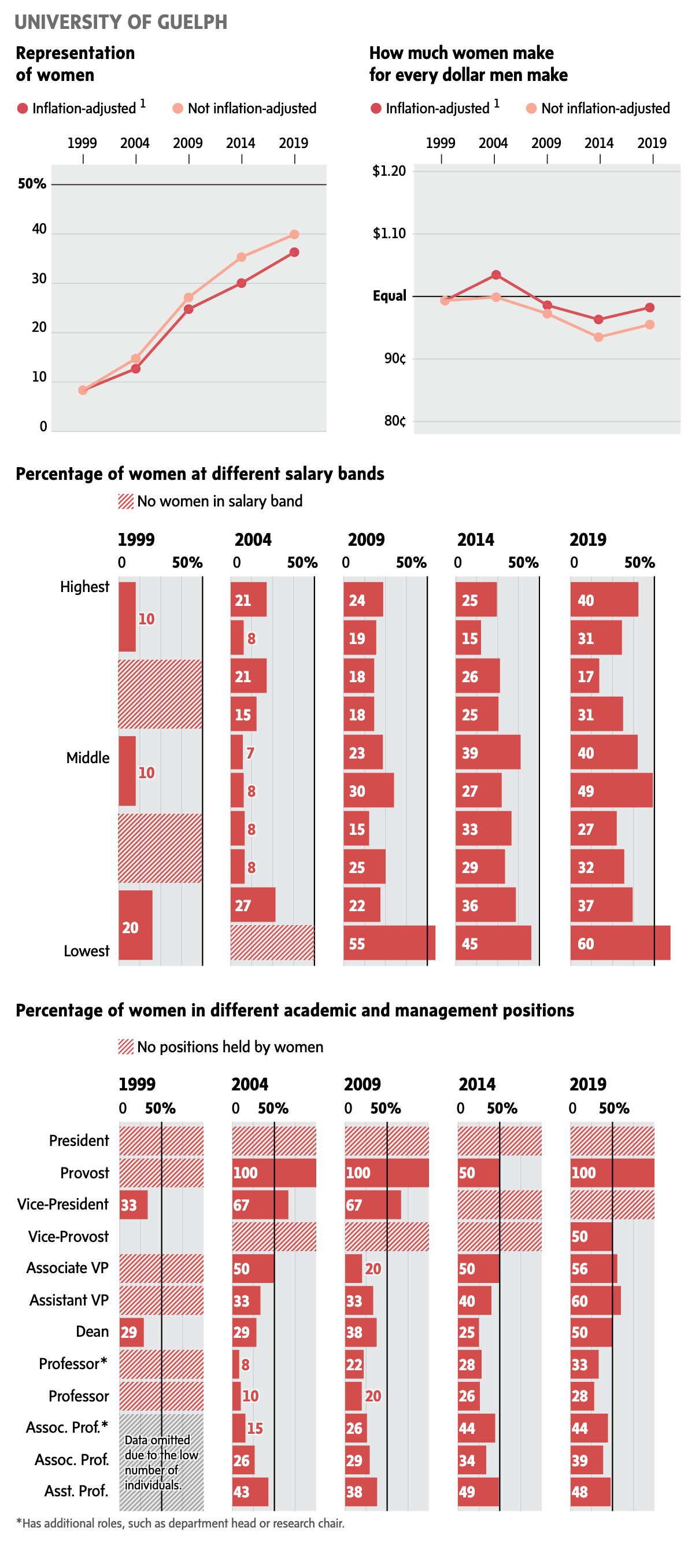

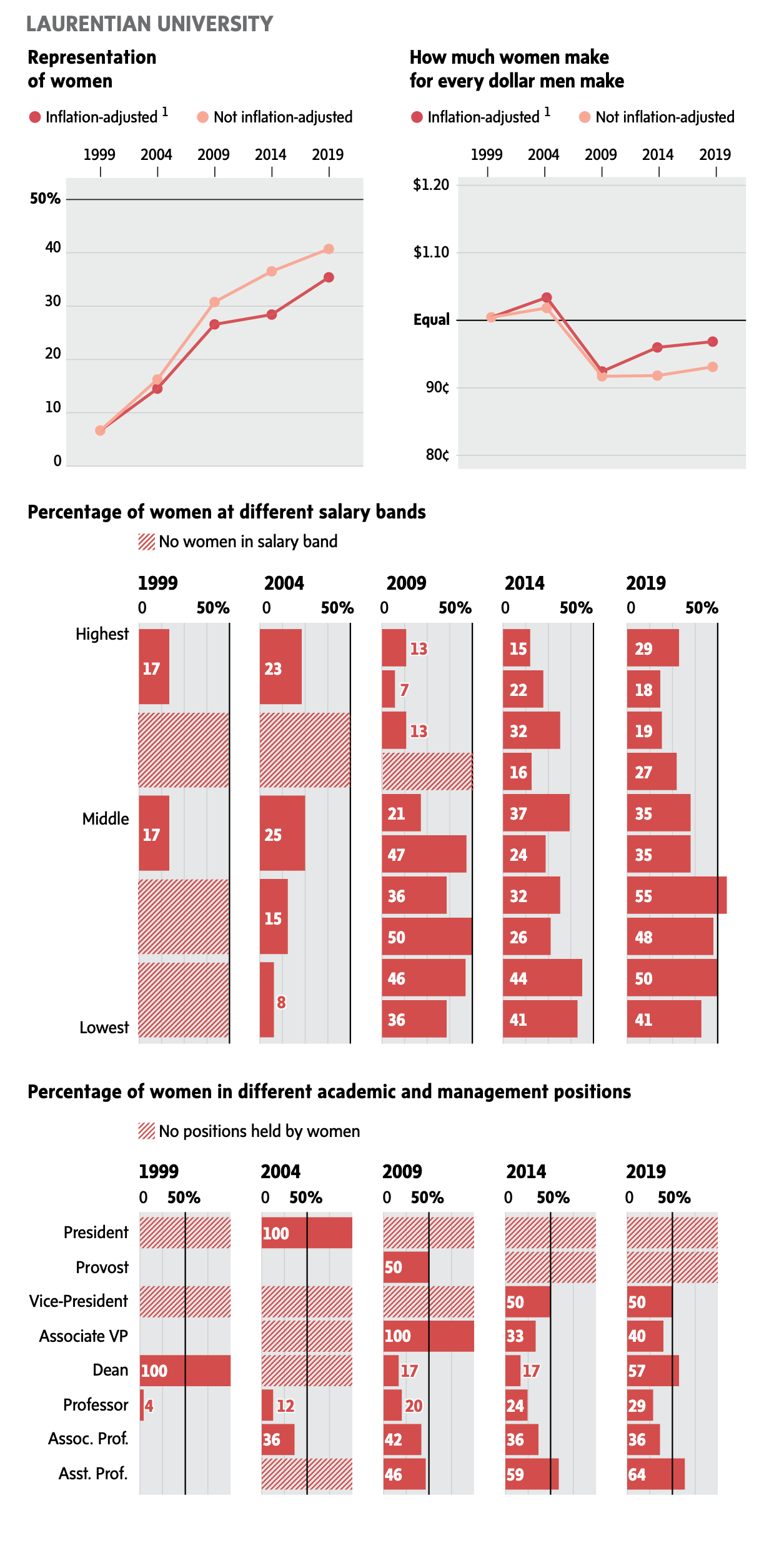

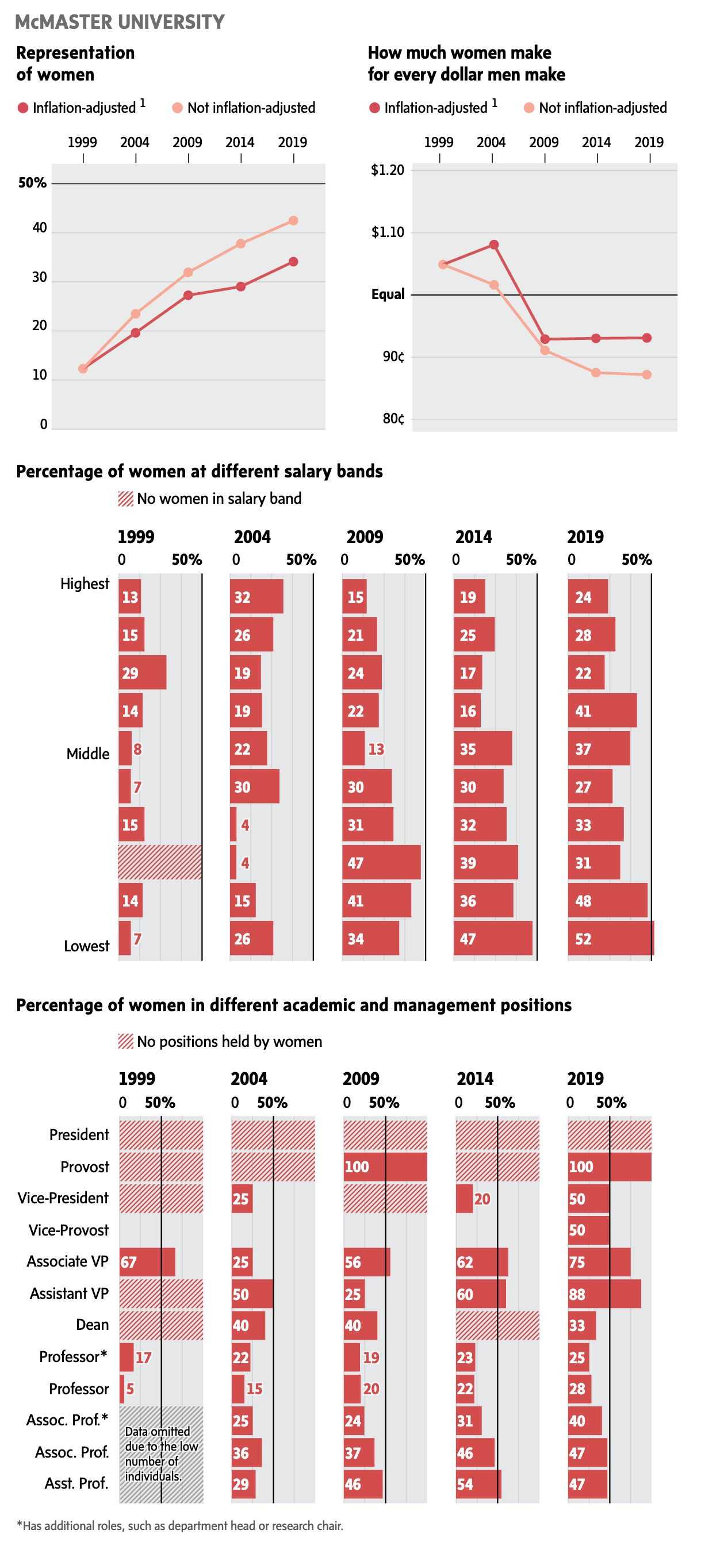

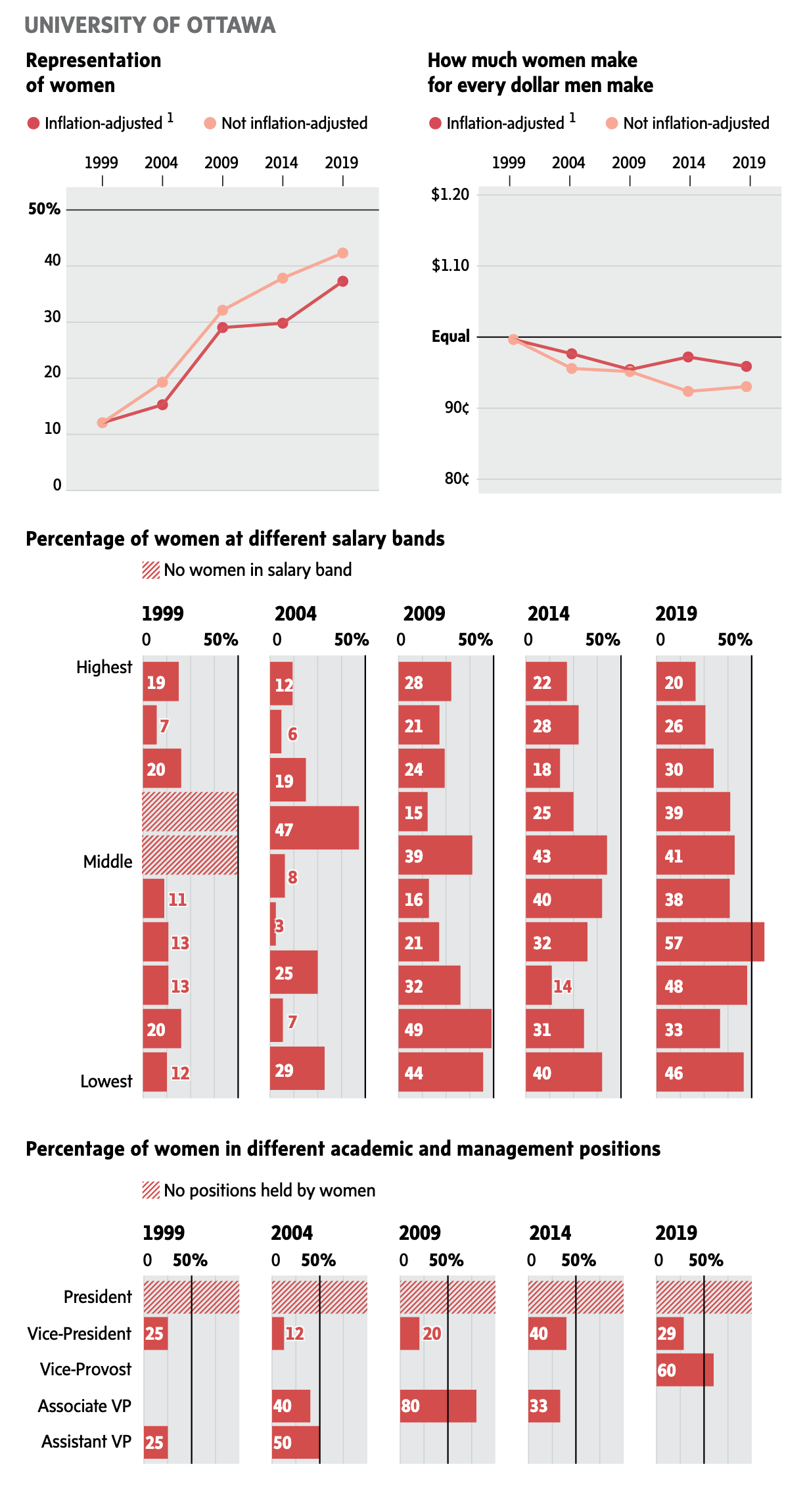

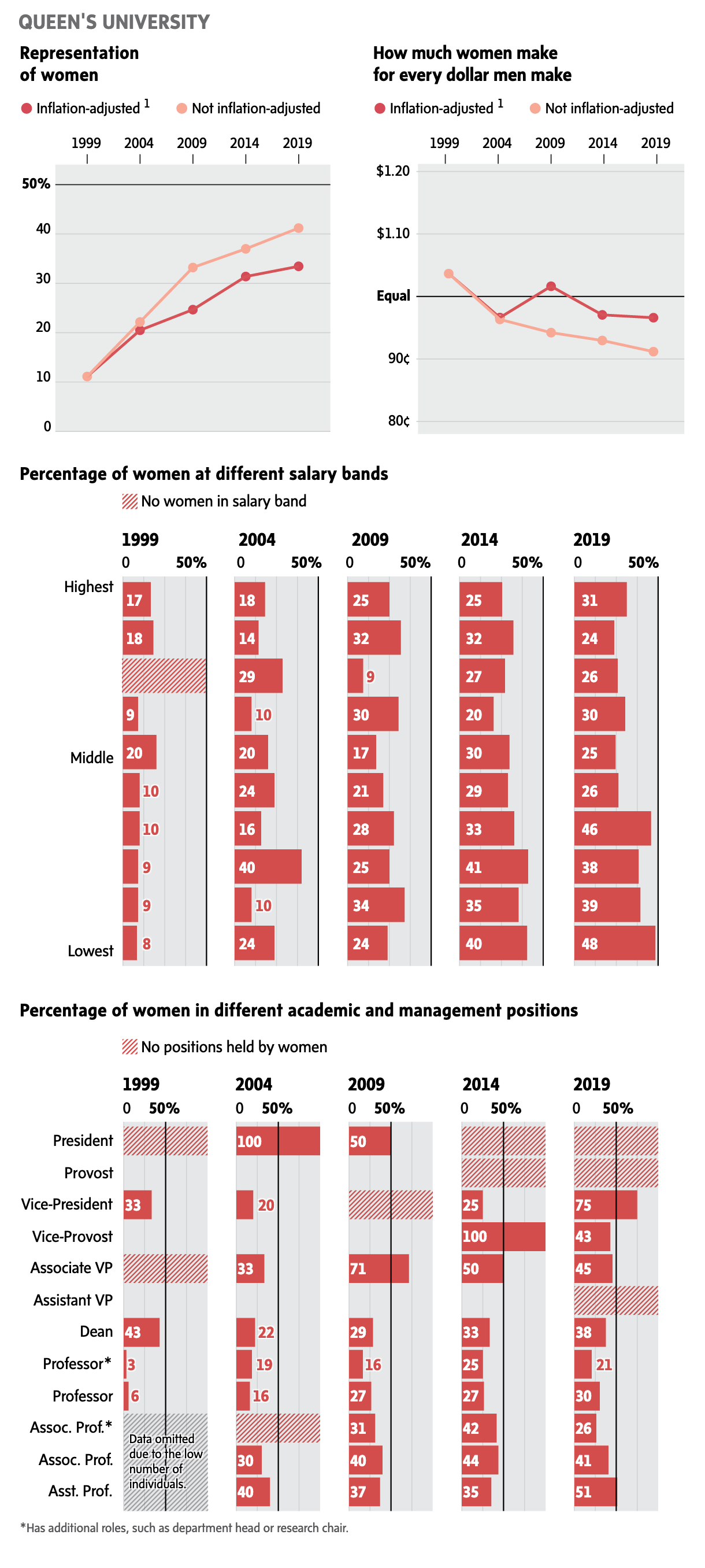

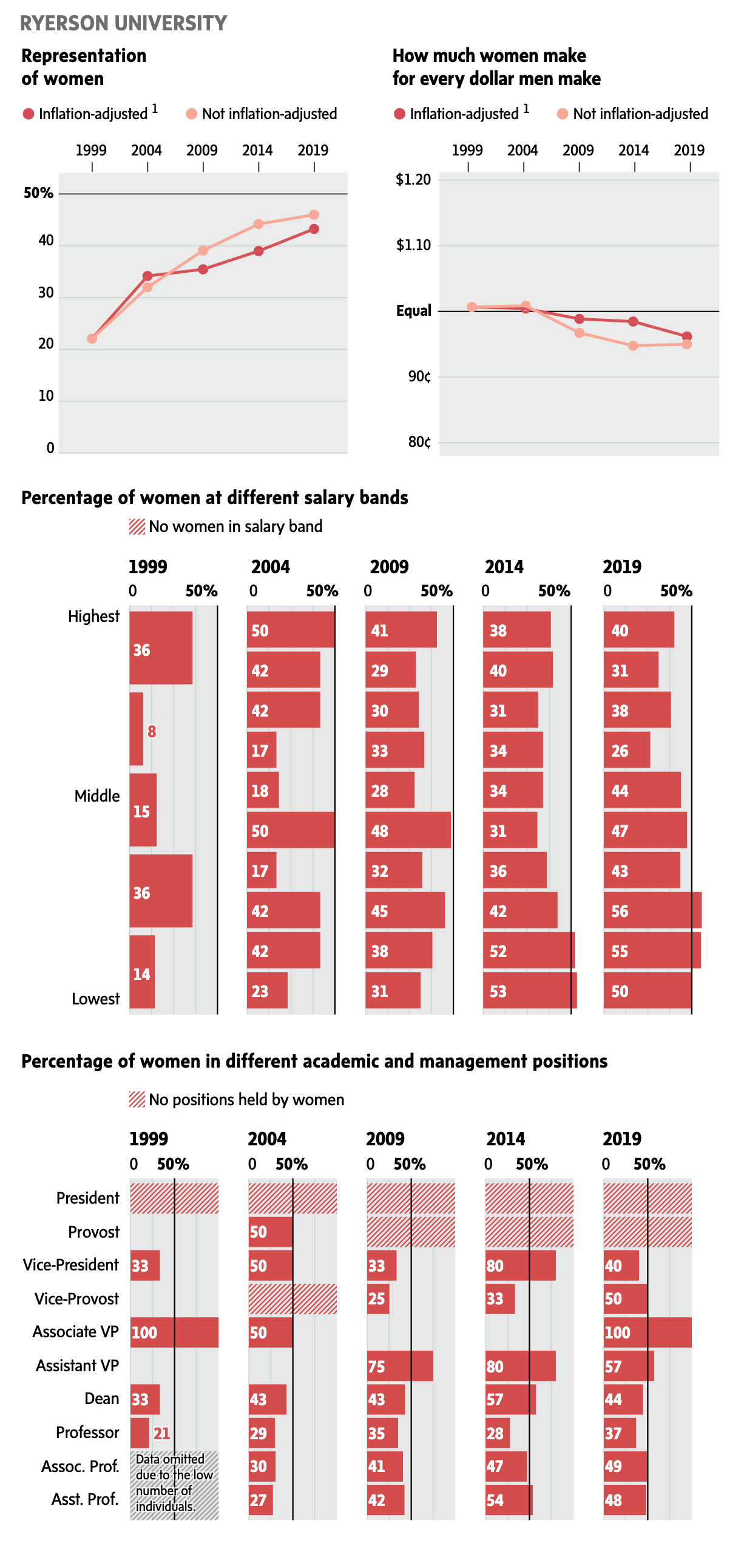

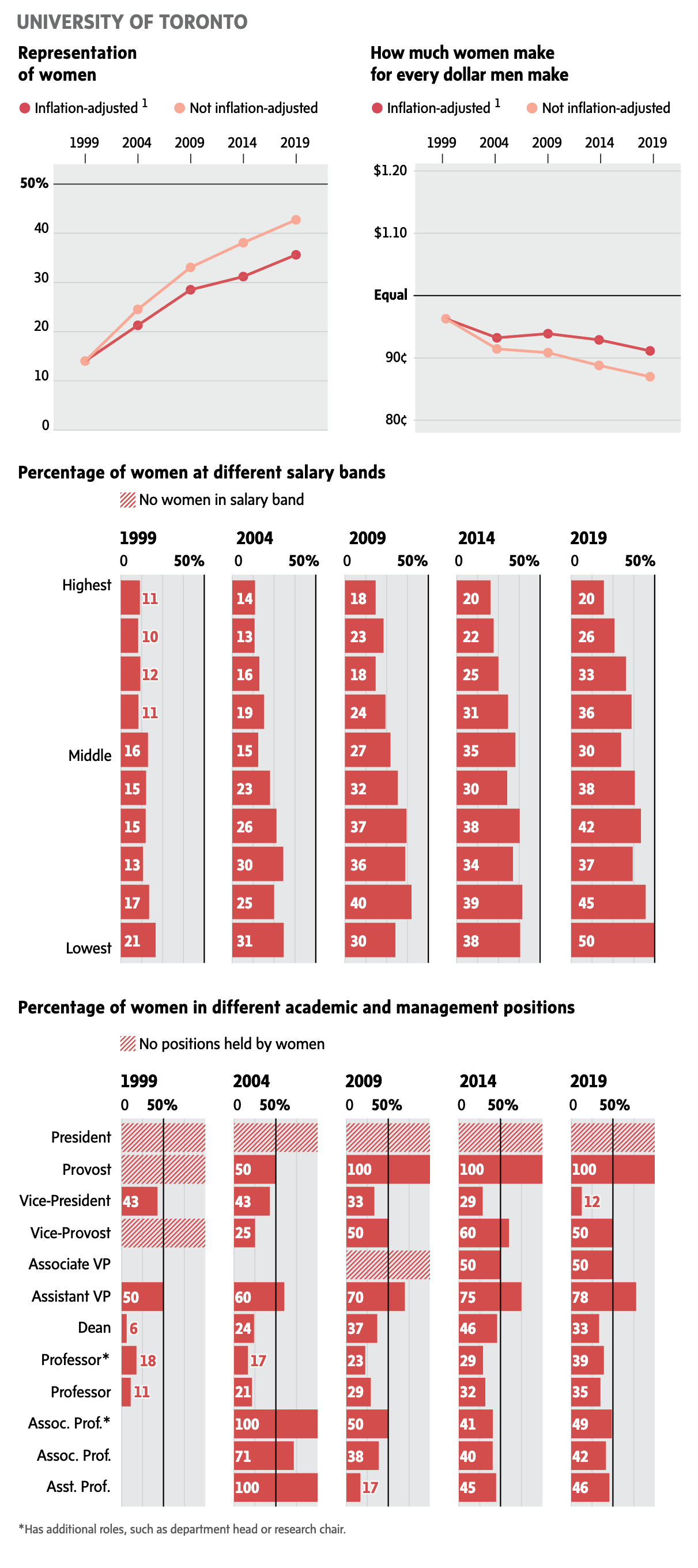

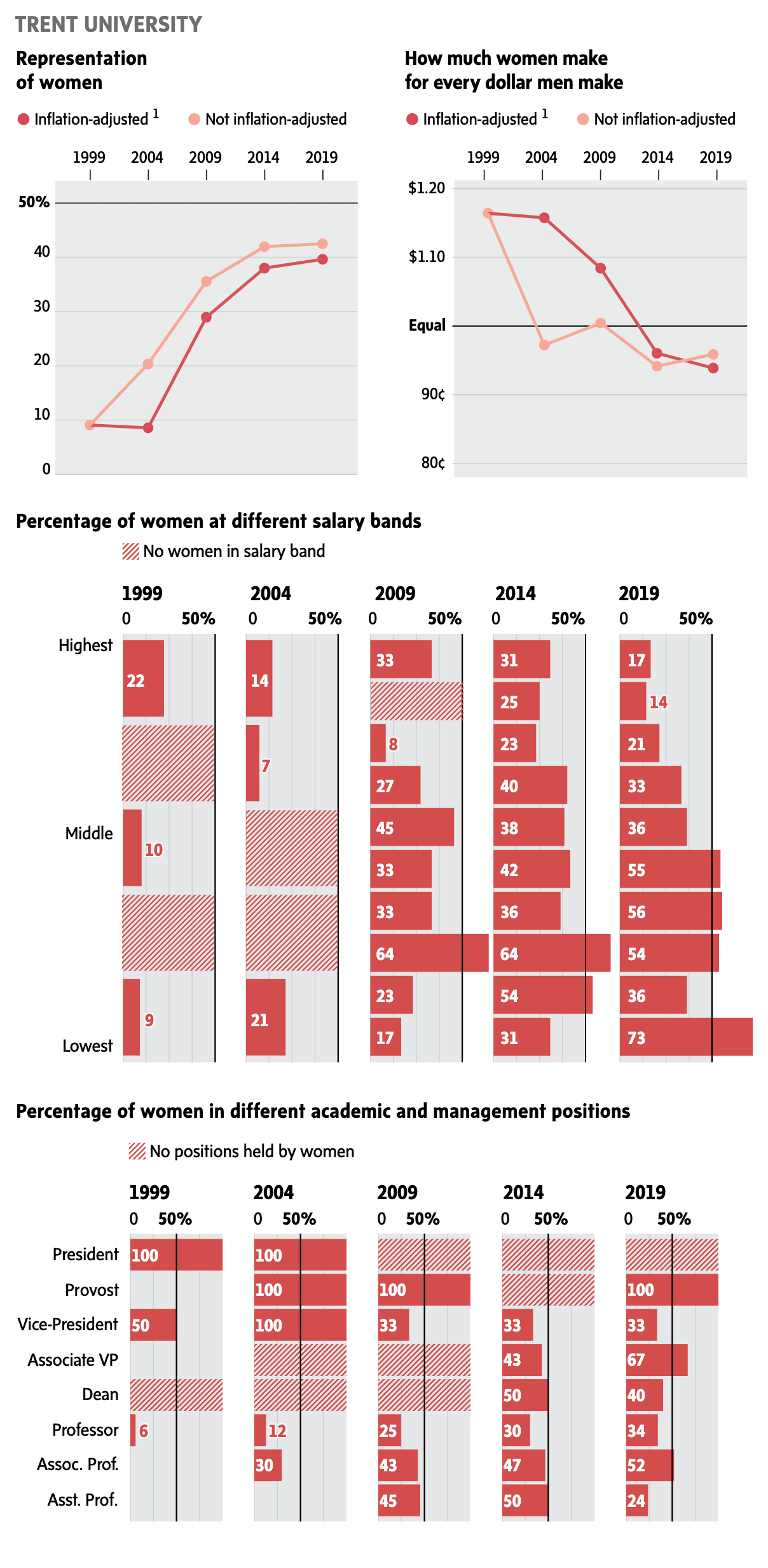

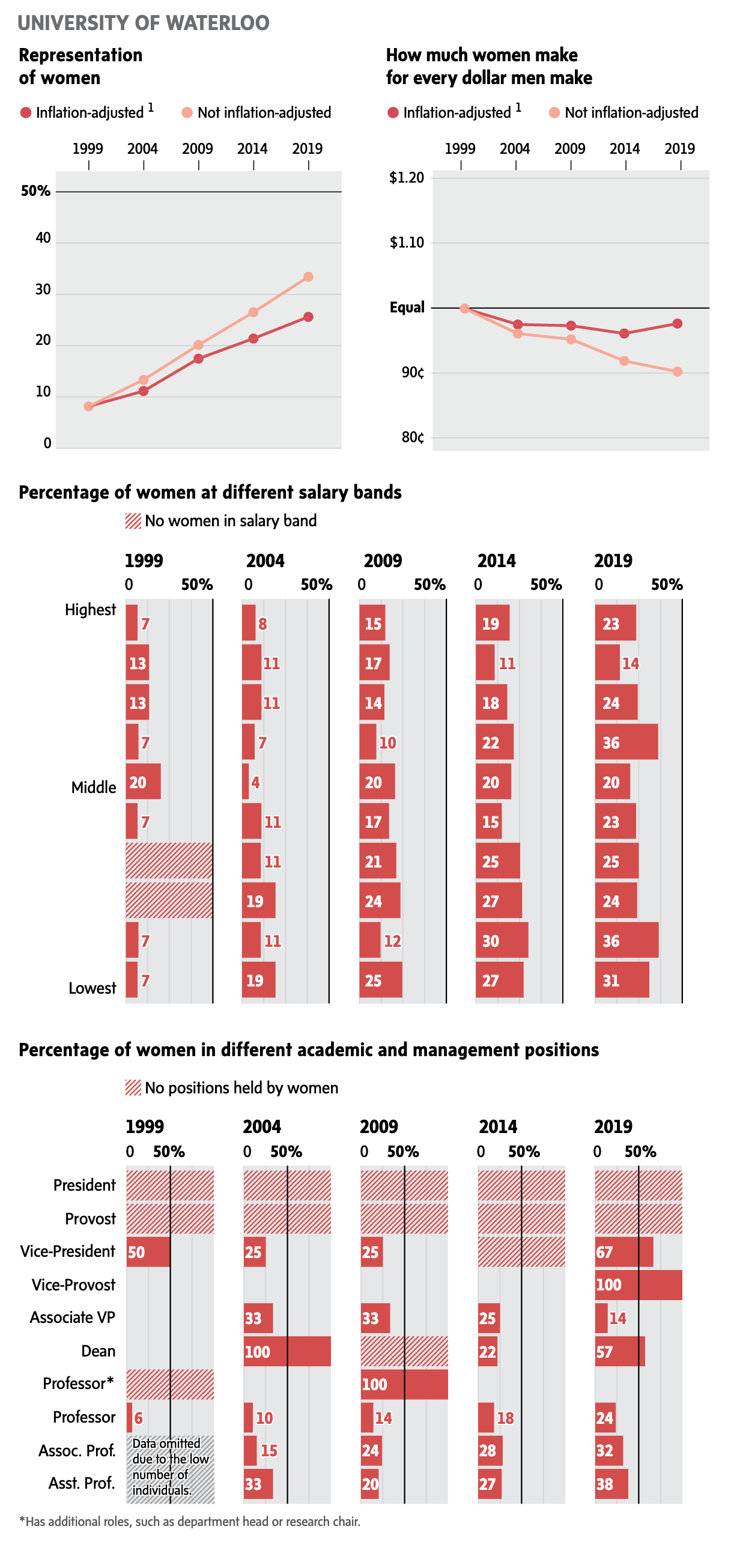

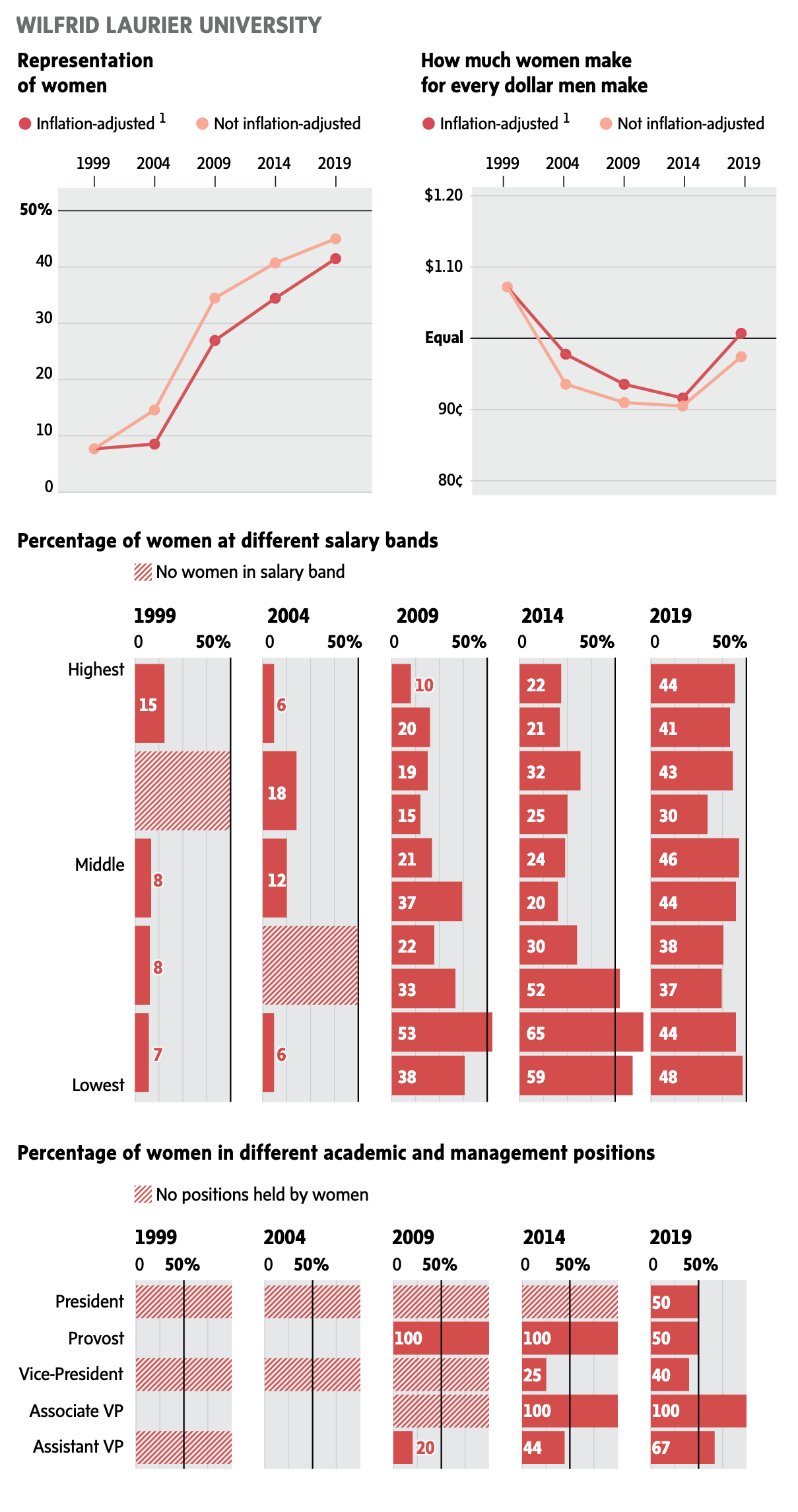

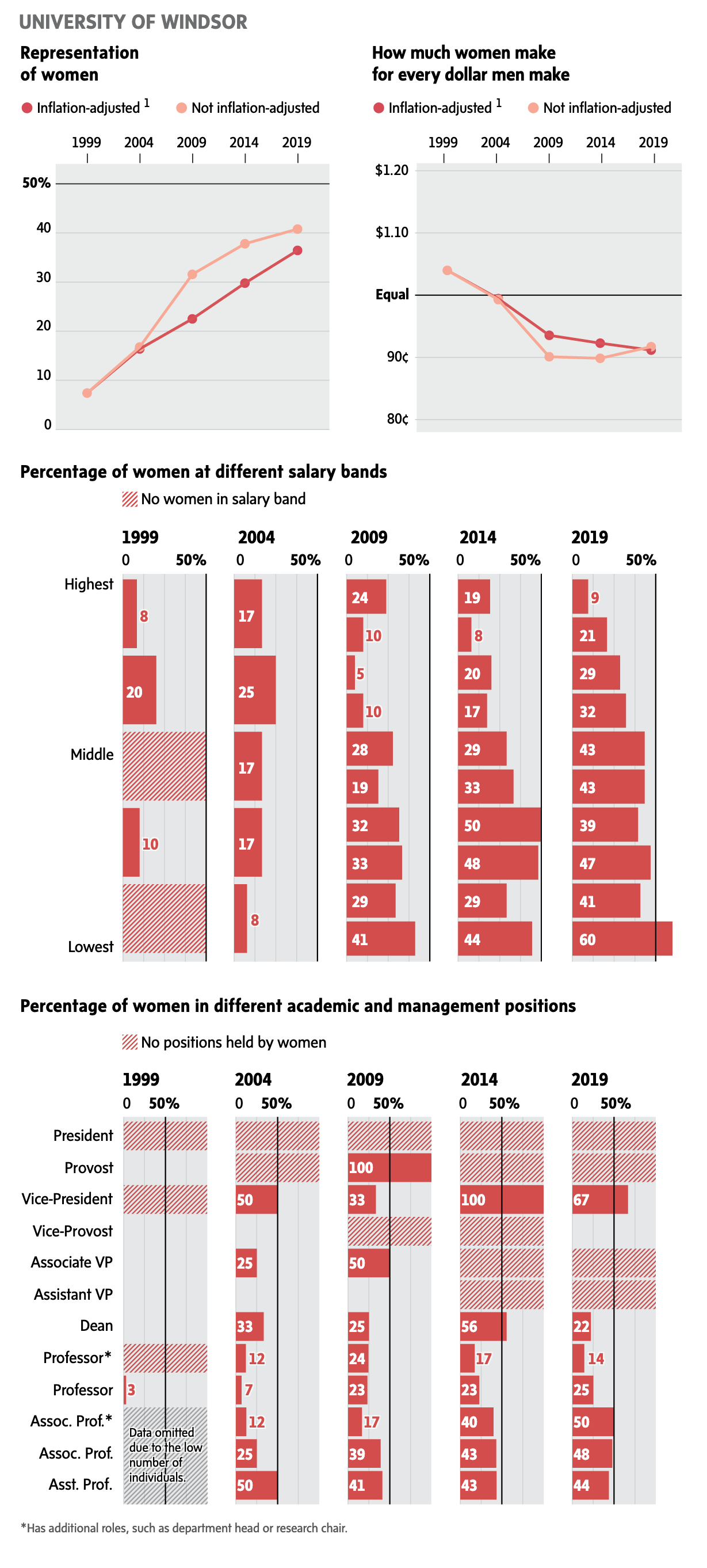

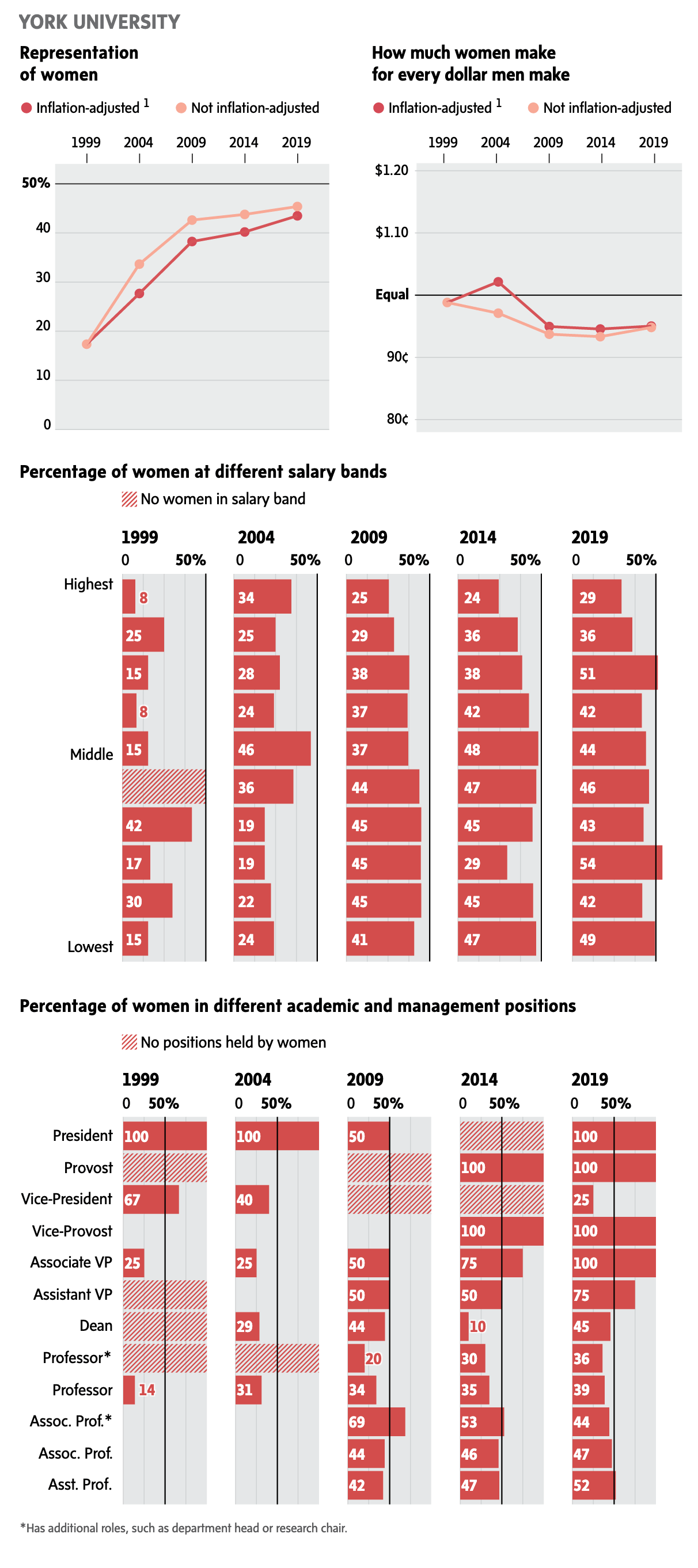

Universities have been promising to fix the sector’s gender problem for decades, but women are still under-represented at almost every level, particularly in decision-making roles, among full professors and senior faculty positions, and in the highest-earning echelons.

The Globe and Mail collected and analyzed public sector salary records in Ontario going back to 1999 to better understand this lack of progress. (Ontario is the only jurisdiction that makes this historical data available.)

In total, 15 of Ontario’s 21 universities were part of the review. (Affiliated colleges were not included.) Only universities that had at least 100 employees on the list as of 2009 could be included; otherwise, small staff fluctuations caused dramatic swings in the findings.

Select a university:

In order to ensure a fair comparison between the years, The Globe adjusted for inflation during salary-related analysis. When Ontario passed the sunshine law in the 1990s, it determined that only employees who earned $100,000 would be subject to disclosure. That number hasn’t changed, but if it had moved with inflation, the new threshold would be $147,537 in 2019. In calculating data points such as overall representation, The Globe only captured employees who would qualify for disclosure if the threshold had kept pace with inflation.

If this had not been done, the situation would look much worse, because women are concentrated in lower-paying jobs. For transparency’s sake, The Globe has provided both the inflation-adjusted and non-adjusted numbers in the overall representation and wage-gap charts.

However, when analyzing the representation among certain job titles – where salary is not being examined – The Globe used all available names. (Many assistant and associate professors currently earn below $147,537 in 2019 and could not have been included otherwise. It is likely many at the lowest teaching levels did not meet the disclosure threshold in 1999 – In fact, there were so few assistant and associate professors in 1999, we did not include them in the analysis.)

To gain a more complete picture of where the imbalances are, The Globe assessed 12 job titles in administrative leadership and academic roles: president, provost, vice-president, vice-provost, associate vice-president, assistant vice-president, dean, professor, professor with additional responsibilities, associate professor, associate professor with additional responsibilities, and assistant professor. (Provosts are often also vice-presidents, but because of their importance within the executive structure, The Globe analyzed them separately. When assessing professors and associate professors, The Globe took into account faculty members who were also listed as having additional duties, such as department head, assistant dean or research chair. This is what “additional responsibilities” means.) Read more about the Globe’s Power Gap methodology.

The overall story is that, two decades ago, nine out of 10 university employees on the Ontario sunshine list were men, as were nine out of 10 professors, nine out of 10 deans and three-quarters of vice presidents. In the ensuing 20 years, schools made notable progress hiring more women, such that they now represent about one-third of university staff. Representation in leadership has also improved significantly – though the bulk of new hires are concentrated in lower-level, less prestigious jobs.

Below, you can see the situation at individual universities in Ontario through the years.