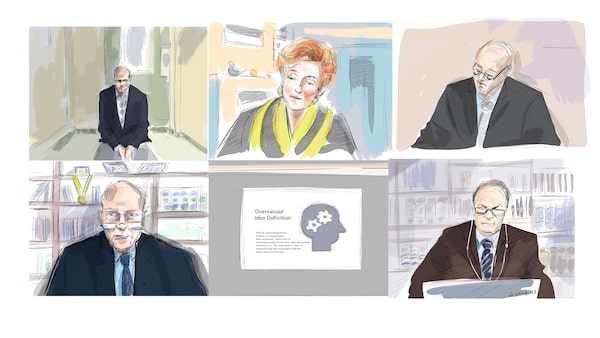

A sketch captures the proceedings in the Toronto van attack trial on Nov. 26, 2020, held over Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic.Alexandra Newbould/The Canadian Press

Thousands of people tuned in earlier this week as the judge overseeing a high-profile trial into one of the deadliest attacks in Toronto delivered her guilty verdict from the basement of her home, with a fireplace and tightly shut blinds as a backdrop.

For some, the highly anticipated ruling in the murder trial of Alek Minassian provided a first glimpse of the criminal court process under the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen many proceedings move online and prompted some in the justice system to work from home.

Over months of hearings culminating in Wednesday’s verdict, the case – which captured public attention across Canada and beyond – shone a spotlight on the challenges and particularities of remote proceedings, from dress codes and home decor to the presence of pets.

One witness, a forensic psychiatrist, testified from a room where several guitars hung from the walls. Court staff as well as the judge, Ontario Superior Court Justice Anne Molloy, warned that their cats may make an appearance during hearings.

Meanwhile, lawyers dressed in business clothes rather than their usual robes throughout the trial – as did Molloy, though she donned her gown for the verdict.

“It may not look like a real courtroom, it may not feel like a real courtroom sometimes, it may seem to be more relaxed, but I can assure that rules of evidence, the rules of law, are not relaxed,” the judge said on the trial’s opening day in November.

Ontario’s courts issued guidance to those in the justice system when the health crisis began last year, as did several legal organizations.

The Ontario Superior Court of Justice, for example, suspended the requirement to wear a gown, but noted participants, including judges, would be “expected to dress in appropriate business attire.” It also advised that participants find an appropriate space to log on.

“We understand that you may not have complete privacy and silence in your current environment, which may be a shared living space, but please do your best to participate from a private, quiet space,” the court wrote.

A task force convened early in the pandemic also laid out best practices for remote proceedings, which included a recommendation that participants consider using an “appropriately dignified artificial digital background” if necessary.

Kathryn Manning, a civil litigator and co-chair of the E-Hearings Task Force, said the group had many discussions on how to maintain a serious tone in the more relaxed setting of the home.

Seeing lawyers and judges in their homes, dressed in less formal clothing, humanizes them and the court process, “and of course all the people in the justice system are people,” she said.

“But on the other hand, it’s still a formal court proceeding and I think you need to respect that and make sure you can replicate it as much as possible.”

The task force is working on updating its best practices now that the justice community has more experience with remote hearings, and there will be some additions related to those kinds of issues, Manning said.

Trevor Farrow, a professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall law school, said the loosening of the rules regarding attire and location for remote hearings has made the court more accessible in some ways, beyond making it easier for people to participate and observe.

The practice of wearing gowns was meant to put everyone on a level-playing field as well as instill a certain sense of formality, but it can also intimidate and alienate people at times, he said.

“So the idea of relaxing the rules around dress codes, in some ways, makes court more accessible to more people in ways that are less intimidating and alienating,” he said.

What’s more, judges, who maintain a significant amount of discretion in how their cases operate, have also had to acknowledge the realities of people’s lives, be it the presence of young children or the sudden ringing of a doorbell, Farrow said.

“Some judges are still saying they don’t want to hear any dogs barking, others are saying, ‘Don’t worry, feel free.’ And so, you know, judges still run their own courtroom and there’s a wide range of practices … within the Zoom community,” he said.

At the same time, being able to see into someone’s home as they’re addressing the court can be distracting and could potentially draw away from their words, he said.

“I do know that lots of lawyers and judges are using the sort of fake backgrounds, or blank backgrounds... because ideally justice is about the merits of a case not, you know, how interesting the background is,” Farrow said.

“Not only from an accessibility perspective, not only from a people taking it seriously perspective, but also as a matter of persuasion, you want the judge to listening to you, not thinking about the guitar behind your head.”

With files from Liam Casey.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.