Photography by Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Louisa Marion-Bellemare and Julie Samson – or Lou-Ju, as they call themselves – are doctors in Timmins, Ont., where drug-overdose rates soared as more synthetic opioids entered the local drug supply.

Most mornings at 6:30 a.m., Louisa Marion-Bellemare and Julie Samson set off for a run together through the streets of Timmins.

The two women work side by side as doctors in the emergency room of the local hospital. Their houses are steps apart. Their families take shared vacations.

They cross-country ski in the winter and take their road bikes out for long rides in the summer. They run in all types of weather, donning goggles to keep their eyes from freezing when the temperature drops into the minus 20s. They compete in triathlons as a pair; Dr. Samson is the faster cyclist, Dr. Marion-Bellemare the faster runner. They are such a tag team that they call themselves Lou-Ju – Louisa and Julie.

But last summer, their talks on the morning run took a serious turn. The doctors were seeing more and more people arrive in the ER suffering from drug overdoses. Some came in “VSA” – vital signs absent.

The surge in overdoses that has been one of the tragic byproducts of the COVID-19 crisis was washing over Timmins, a rough-and-ready mining town of 45,000 in northeastern Ontario. Its rate of overdose death was the highest in Ontario and nobody seemed to be doing a damned thing about it.

The local addiction-treatment centre had closed for the pandemic, a fact that still makes Dr. Marion-Bellemare turn the air blue with outrage. The detox facility where drug users go to get sober before starting treatment shut its doors, too.

The hospital had no place for overdose survivors to recover and get treatment. Its attitude to those who kept coming into the ER, Dr. Samson says, was a weary, “Oh, here’s Joe again, coming in on an overdose.”

People were dropping left and right and Timmins was turning its back. That made the doctors really, really mad.

“What the hell are we doing here?” Dr. Marion-Bellemare remembers thinking. “Something has to change. We aren’t helping people at all. These are otherwise young, healthy people. Their only health condition is their substance-use disorder. They are dying and they shouldn’t be dying.”

So they decided to make some noise. Over the next few months, these two angry, funny and very persuasive women would shake up the city’s health care establishment and transform the way it treats its drug problem.

Sydney Wesley, top, shows heroin track marks on his arm dating back to 2011. He says he never uses drugs alone and always makes sure a naloxone kit is nearby. Such kits are commonly left behind at sites drug users are known to use, like the one hanging on the stair railing at bottom.

Although they seem joined at the hip, the two friends come from very different backgrounds.

Dr. Samson grew up in a comfortable French-Canadian family in Ottawa, the daughter of a doctor who worked in the army and later at Ottawa General. She went to medical school in Sudbury, came to Timmins on a year-long commitment and ended up staying.

Now 50 and married to another emergency doctor, she has three children, at the ages of 21, 19 and 17.

Dr. Marion-Bellemare, 43, was born in Red Lake, another Northern Ontario gold-mining town, even more remote than Timmins. Her father left when she was 3, leaving her alcoholic mother to raise her and her sister. Her mom worked nights in a bar to help pay the bills.

After finishing high school in Timmins, Dr. Marion-Bellemare did a degree in kinesiology and got a job as a mine inspector in British Columbia, one of the first women in the province to hold that position. She married and had a daughter, now 7. When her mother turned up drunk to babysit when her daughter was 10 days old, Dr. Marion-Bellemare decided she could not have her mom in her life anymore. She still weeps with regret at the decision.

Like many of the patients she now sees, her mother was suffering from an addiction she could not beat. She died of an alcohol-induced seizure in the very hospital where Dr. Marion-Bellemare now works. “My hospital,” she says. The doctor had not seen her for five years.

Dr. Marion-Bellemare can be a heated speaker in meetings, but on her rounds around town she'll call people 'honey' and relate to them personally.

The two women differ in temperament, too. Although neither is exactly a shrinking violet, Dr. Marion-Bellemare is the more intense and sometimes blunt of the two. She drops F bombs like a B-52 and doesn’t hesitate to confront those who she thinks are getting in the way of their campaign. The two have developed a “safe word” to keep Dr. Marion-Bellemare in check. When she is getting a little too heated in meetings, Dr. Samson hisses: “Louisa: Butterfly.”

Dr. Marion-Bellemare calls everyone “honey” and seems to know half of Timmins personally. Dodging around in an aged avocado-green Honda Element, she pauses every couple of blocks to wave at someone through the windshield: a neighbour, a patient, a work pal. She is such a woman about town that Dr. Samson calls her “the mayor.”

When she wants something done, she is like a dog with a bone. “You could say she is persistent,” says a smiling Craig Ruscitti, a commander at the ambulance station who has known her since they were teenagers.

Dr. Samson is more diplomatic, if just as passionate. She talks about her work so much that her family instituted no-addictions Fridays, prohibiting her from discussing the topic for the whole day. With more than 20 years as a local doctor, she is known and respected around town – “older and wiser,” says Dr. Marion-Bellemare, who became a doctor only seven years ago.

Like most close friends, they sometimes drive each other crazy. Dr. Samson complains that her pal won’t shut up, which is fair: Even her kindergarten report card said “Lousia talks too much.” Dr. Marion-Bellemare says that Dr. Samson is a micro-managing nudge, always sending her annoying to-do lists for their latest project. And like most, they laugh a lot, especially about the weird stuff they see at work. Like the time a patient left behind a large sex toy then came back to claim it “for a friend.”

Together they make a formidable team, persuading doubters with a mix of facts and fury. They would need both to change the closed little world of addiction treatment in Timmins.

A note on a Timmins rental property's back door asks people not to use needles nearby.

The city lies in the mineral-rich heart of the Canadian Shield about halfway between James Bay and Georgian Bay. Giant mine trucks roar down the main street. Every second vehicle is a hefty pickup. The singer Shania Twain grew up poor in Timmins.

Its addiction issues go back a long way. The influx of miners brought booze, drugs and prostitution. When the opioids crisis broke out with the proliferation of highly addictive pain pills, Timmins was hit hard. But that was nothing compared with what would happen when fentanyl came to town. The synthetic opioid is many times more powerful than heroin. Overdose deaths rose from 10 in 2018 to 20 in 2019 to 31 last year, a shocking figure for a city of its size. That far outweighed the toll from COVID-19. The disease claimed nine lives last year in the local Porcupine Health Unit, which includes Timmins.

These days, sirens sound around the clock as paramedics race to revive the latest overdose victim – if they manage to get there in time. In the bleak downtown, people retreat to doorways, empty lots and cheap apartments to smoke, snort, ingest or inject their drugs, which can come in deadly cocktails of everything from speed to horse tranquilizer.

A local Facebook group wells up with grief over those who have lost their lives – a 39-year-old father of four, a young man who was happiest sitting by the campfire, a fashionable 20-year-old woman who wouldn’t leave the house without her lashes on – and outrage at those who sell fentanyl. Organizers of the group, called No More, have even protested outside the houses of drug dealers, waving placards saying “Stop the Murder” and “Save Our Community.”

This is what the doctors were up against: a raging epidemic of drug overdoses that was overwhelming a small northern city far from the big hospitals and treatment resources of the south. Despite the huge change wrought by fentanyl, the way Timmins handled its drug issue had hardly changed in years. The local treatment centre focused on abstinence. Private methadone clinics handed out the drug to those with prescriptions. At the hospital, emergency doctors thought it simply wasn’t their business to treat the addicted people who came through the doors to the ER.

Some local agencies that deal with drug users were complacent and hidebound, Dr. Marion-Bellemare says. They guarded their turf and hoarded their funding. Their basic way of doing things had not changed in decades. Even though people were dying in the streets, she says, they were “putting up their feet and drinking their coffee every day.”

The doctors knew they would need allies if they were going to turn things around. Dr. Marion-Bellemare started by calling the mayor, former mining executive George Pirie – naturally, an old family friend. He knew and admired her as a straight shooter who wasn’t afraid to ruffle feathers. She told him something had to change. He agreed.

Pulling in all their contacts and drawing on resources they barely knew they had, they called an online crisis meeting for Oct. 13 and invited everyone who mattered: the city manager, the police chief, the local member of parliament. The doctors spent weeks putting together a fact-filled presentation, firing ideas back and forth by text and FaceTime late into the night and through the Thanksgiving weekend.

Vicky Bernard, manager of the mental-health program at the Timmins and District Hospital, holds a framed photo of her late son, Joey, from 2017.

On a Tuesday evening, breaking into nervous sweats, they opened their laptops and began to speak to an online audience of 60. They kicked off with some jaw-dropping numbers. The rate of death from drug overdose in Timmins in 2019 was 46.8 for every 100,000 people, four times the Ontario figure and double that of Vancouver, the epicentre of the crisis. Things were looking even worse in 2020. The city had seen 12 overdose deaths in the first half of the year. Four more people had died just in the seven days before the meeting.

To put a human face on the figures, they introduced Vicky Bernard, a colleague from the hospital. She choked up as she told the group how her 25-year-old son, Joey, died of an overdose only months before. He had once been kicked out of treatment for breaking the rules and carrying suboxone, an addiction medicine prescribed by doctors to control drug cravings. In other words, the doctors say, he was ejected for carrying a medication designed to help people with addictions get better.

Timmins, they told the sombre crisis meeting, was failing to meet the minimum standard of care for the city’s vulnerable drug users, many of them poor and Indigenous. If users wanted help withdrawing from drugs, they would have to find their way to the nearest detox facility in Smooth Rock Falls, a full hour away. If they wanted to try a residential addiction program, they would have to get on a waiting list, making sure to call when the supervisor was on shift. If they simply wanted a place to use their drugs in safety, an option now available in Canadian cities from Victoria to Halifax, they were out of luck. Despite its appalling death rate, Timmins had no supervised-injection site.

The doctors put it bluntly: “The status quo and our inactions are contributing to deaths.” To make a difference, the city would need to make it far easier for users to find a treatment or detox bed. It would need to start treating drug use not as a crime or a sin but as a chronic medical condition like diabetes or heart disease. It would need to embrace the latest thinking on addiction and treat it promptly with the latest addiction medicines. Above all, they said, it would have to “put our biases aside and become comfortable with the unfamiliar.”

A couple of weeks later, the doctors took their case to Timmins City Council. At a typical meeting, the mayor and eight councillors deliberate over matters such as the purchase of soil and sand to cover the local garbage landfill. This was a different kind of day.

Dr. Samson told council that with so few options in Timmins for detox or treatment, many drug users were ending up in the doctors’ emergency department fighting for their lives, only to be revived and sent back out the door. “There is nowhere for them to go,” Dr. Marion-Bellemare said. “Three days later they go out and they use, and three days later they come back and they are deceased in our emerg.”

The presentation left some councillors in tears. Mr. Pirie said it was time to act. “We have the moral authority to end the apathy in this community,” he told council.

Nathaniel Vaillancourt, top, and Michelle Couture, bottom, go on outreach walks for the Living Space, a group seeking to end homelessness in Timmins. Its workers clean up sites where people have been using drugs and make contacts in the community. Ms. Couture is pointing out messages on a door that street people use to relay information.

Things moved quickly after that. The hospital opened a couple of detox beds for patients who show up in crisis. If they want help coping with their addiction, doctors help them get through their withdrawal, then offer to get them on suboxone, the addiction medicine, within three days. Many patients agree to take a long-acting form of the drug that is delivered in a single shot and lasts a month. That means they don’t have to keep track of their pills and remember to take them. People have started asking the doctors to put them on “the needle.”

The new program has helped 71 people since December. One of them is a young woman who ended up in emergency after an assault left her lying in a snowbank, bound with an electrical cord. The doctors got her on addiction medicine and she hasn’t used street opioids since.

Another is a woman in her 30s who was pregnant when she came into the emergency department with pneumonia. Dr. Samson gained her confidence and got her into a detox bed. The woman handed the doctor a stash of drugs she had been hiding, saying, “I’ve had enough of this, doc.” After a couple of relapses, she righted herself and gave birth to a baby girl. The doctors got her into a residential treatment program in Toronto, where she can keep the baby and get better.

Before the doctors spoke out, prisoners suffering from withdrawal in the police lock-up would languish there, often showing up in court in miserable shape. Now, doctors from a special addictions team visit and treat them in the cells. Before, the local rapid addiction-medicine clinic, or RAAM, one of about 100 across the province, was open only three half-days a week. Now, it’s open five full days and takes walk-in visitors.

Under pressure, the city’s only residential treatment facility reopened after eight months. Even better, the doctors say, it now takes people who are on methadone or suboxone.

Perhaps the most remarkable change is the new police unit dedicated to helping drug users instead of busting them. Two veteran officers, Leah Blanchette and Bill Field, circulate around the city trying to build rapport with people on the street. To break the ice, Constable Blanchette started baking muffins and handing them out, leading one local woman to dub her “the muffin cop.”

Dr. Samson has had more resources to help drug users in crisis since she and Dr. Marion-Bellemare spoke out.

The doctors can’t get over how much progress they have seen since they started banging their drum. The city’s leadership has awoken to the scale of the crisis. Organizations that barely spoke with each other are pulling toward a common goal. In April, the city teamed up with mental-health and addictions groups to prepare a request for $19.5-million in provincial funding. The money would go to everything from new walk-in clinics and more detox beds, to research into a supervised-injection site and better training for those who work with substance users.

“Multiple organizations in our community have changed the way they think, have changed their language, have changed their culture,” Dr. Marion-Bellemare says. “I’m actually astonished by it. When I think about what has happened in six months, it’s crazy.”

Mr. Pirie is full of praise for what the doctors have done. They may have “stepped on some toes and hurt some feelings,” but it was worth it, he says. One of Ontario’s top addiction doctors, Meldon Kahan of Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, calls them phenomenal and inspiring. “It’s kind of wonderful to see that amongst all the other negative and cynical things that are happening, there are people that have shown such courage and idealism, fighting for what’s right.”

The doctors know their fight is far from over. Drugs continue to exact a devastating toll on Timmins in spite of all the new efforts. Authorities reported 15 fatal overdoses in the first quarter of this year. If that pace continues, it will far exceed even last year’s shocking record.

Overdose calls are depressingly commonplace for paramedics and police. When The Globe and Mail was visiting earlier this spring, Constable Field of the police outreach team took a call on his walkie-talkie. A man’s body had been found. He rushed off to deal with yet another fatal overdose.

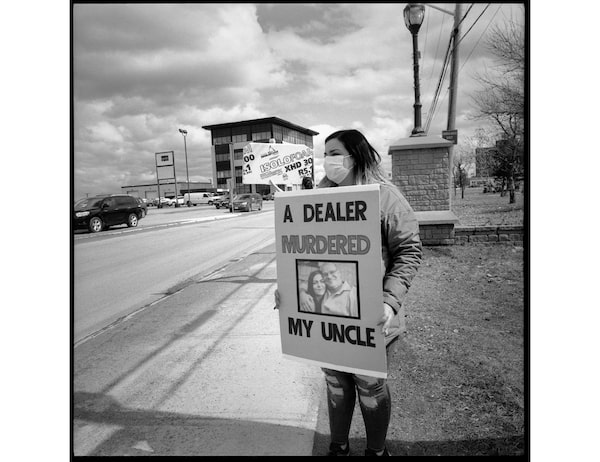

Amy Herbstreit, a house cleaner, protests in Timmins. She says she lost a relative to drug use when he overdose on crack laced with fentanyl last year.

Despite all the support they are getting from community leaders, not everyone in Timmins is behind the doctors’ harm-reduction approach. Like many communities, Timmins makes overdose-reversing kits and sterile drug-use equipment available to users.

“Why waste your money giving out needles. That’s just covering up the problem,” said Amy Herbstreit, a house cleaner, whose uncle died of an overdose last fall. At a No More protest this spring, she held a sign saying “A dealer murdered my uncle.”

Dr. Marion-Bellemare says the doctors still face resistance from some organizations, too. They remain defensive and territorial. “We were whistle-blowers,” she says. “We made some enemies.”

But they show no sign of letting up. Dr. Marion-Bellemare works 70-hour weeks and several jobs, putting in hours not just in the emergency room, but at the homeless shelter, the local Indigenous health centre and back at the hospital as addictions lead, not to mention working trips with Dr. Samson to the Attawapiskat First Nation on James Bay. As if that were not enough, she has taken on a new job working in addictions at the regional prison. Dr. Samson would like to slow down but finds herself completely caught up in the campaign. Both doctors have the added burden of helping deal with a new surge of COVID-19 that led Mr. Pirie to declare an emergency last month.

When the doctors aren’t working or organizing, they are watching over their patients, a hands-on affair for both. Dr. Samson often stops to say hello to patients she sees on the street, fetching them coffee or bags of groceries if they seem in bad shape. If one of them fails to show up for an appointment, the doctors will go looking for them in person. When one agitated patient ran out of the ER in nothing but his hospital gown, Dr. Marion-Bellemare jumped in her Honda to catch up with him. They joke that “people can’t escape us.”

As a result, they have become well-known figures on the rough side of town, where people call them simply “the doctors.”

When Dr. Marion-Bellemare was on a run one recent morning, she passed a man she knew who was on crutches. He mimicked running alongside her, making the doctor and her running pals roar with laughter. Another day she and Dr. Samson stopped to kibitz with a group of guys drinking in a vacant lot. Which of us is better looking, the doctors asked. Which is smarter?

As successful as their campaign has been, the doctors have big plans for even more change, even better addiction services. They would like to see more detox beds at the hospital (10 instead of two), a new one-stop “centre of excellence” putting services for substance users under one roof. They also want to move ahead with the controversial concept of “safe supply”: giving safe prescribed drugs to designated users, as some doctors in Vancouver and other cities are doing.

Lately, they have been pouring their energy into preparing a proposal for a supervised-injection site. They expect a struggle. Many residents see such sites as magnets for crime and disorder that enable rather than address drug addiction. So the doctors plan to be prepared. On their 6:30 a.m. runs, they talk about how to clear the demanding application hurdles and whether to apply for a temporary site in the meantime.

If the doubters think their campaign is finished, Dr. Samson says, they have another thing coming. “I think they hope we will just quietly fade away,” she says. “I don’t think we will just fade away.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DUQUWT2YNZEVDLSHEC26EQQMFY.JPG) The buddy system

The buddy system

For someone at risk of an overdose, a naloxone kit can be a lifesaver – but sometimes only if someone’s close by and willing to act within minutes. On the streets of Oshawa, Ont., some users are learning to save themselves, Marcus Gee reports.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.