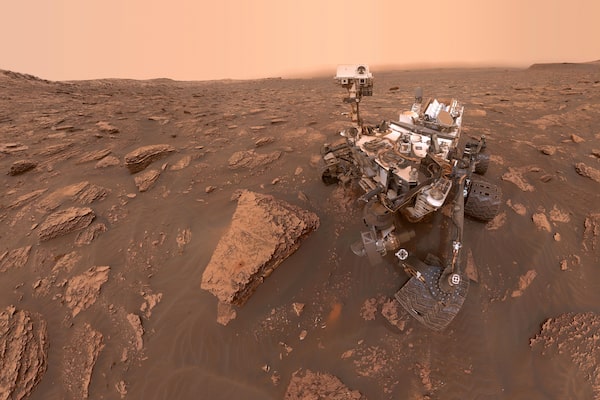

A self-portrait taken by NASA's Curiosity rover at the Gale Crater, at the center of which stands Mount Sharp, June 15, 2018.NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS/Supplied

A brief whiff of methane has set the internet bubbling with talk of life on Mars, but scientists affiliated with NASA’s Curiosity Rover caution that it is too soon to know if their remote controlled vehicle has provided an accurate measurement of the trace gas or, if it has, what the source of the methane may be.

On Sunday, officials at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., confirmed that last week Curiosity detected a sudden spike in the amount of methane in the air near its landing site in Gale Crater. The amount – just 21 parts per billion by volume – is minuscule by Earth standards, but it was enough for the U.S. space agency to call it a “surprising result" in a statement released after the preliminary finding was reported by the New York Times on Saturday.

“This is much higher than any previous detection [by a spacecraft at Mars], and almost one hundred times the background value of methane for Gale Crater," said Isaac Smith, a planetary scientist at York University in Toronto who is not a member of the rover’s science team.

Because most of the methane in Earth’s atmosphere is derived from biological sources, the finding generated a wave of media stories hinting at the possibility of extra-terrestrial life on the Red Planet in the form of methane-producing microbes beneath the soil.

Scientists expressed far more caution in their interpretation of the measurement, pointing out that there are non-biological ways to generate methane if the right kind of rocks are in contact with water below the Martian surface. It also need not be the product of any process that is taking place on Mars today. Instead, it could be a relic from the planet’s remote past when the interior was warmer and more geologically active.

“The methane could have migrated around the subsurface and it could have collected in places where it would have been trapped," said Dorothy Oehler, a researcher with the Planetary Science Institute in Houston and a former member of Curiosity’s science team.

She added that while there’s no indication there is a biological explanation for the methane, such a possibility can’t be discounted.

“It’s possible, but we just don’t know,” Dr. Oehler said.

Whatever it means, methane on Mars presents a scientific conundrum because it has only been detected at rare and brief intervals. In fact, until recently, it was unclear which, if any, of several positive methane results reported by various spacecraft and astronomical observatories since 2003 could be trusted.

The evidence was bolstered in April, when a team of scientists, including Dr. Oehler, found that an earlier methane spike observed by Curiosity in June, 2013, was also captured in data from Europe’s Mars Express spacecraft, as it orbited overhead at that time.

But if methane is seeping out from time to time at Gale Crater and, presumably, in other places on Mars, scientists are still not sure why it vanishes so quickly. Calculations show that methane should linger in the Martian atmosphere for centuries before it is broken down by ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Coincidentally, a study by a Danish team that was published Saturday in the journal Icarus suggests that methane released on Mars could be rapidly taken up by electrically charged grains of sand blowing around in the planet’s thin atmosphere.

NASA said that scientists working with Curiosity have quickly organized a follow-up measurement to see if the methane that the rover detected last week is still present.