Odysseus lunar lander captures a wide angle view of Schomberger crater on the Moon, in this supplied photo released by Intuitive Machines February 23, 2024.INTUITIVE MACHINES/Reuters

The Odysseus lunar lander, alive but off-kilter, is transmitting data from the moon as engineers try to make the most of the spacecraft’s limited lifespan and communication capabilities.

On Friday, Intuitive Machines Inc. of Houston, Tex., revealed that the lander is positioned horizontally at its landing site near the moon’s south pole.

Temperature readings and other data suggest it may be resting on a rock rather than completely tipped over. While it is receiving enough sunlight on its solar panels to maintain power, its high-gain antenna cannot point toward Earth.

Instead, the lander’s radio signals are likely skipping off the lunar surface, and quite weak by the time they are received. Constrained by the reduced bandwidth, photos that could reveal more about the condition of Odysseus can only be relayed back slowly.

“What’s clear is that the lander is not in the orientation that had been anticipated,” said Christian Sallaberger, president of Canadensys Aerospace. The Ontario-based company supplied several cameras for the mission including those that showed the spacecraft during its departure from Earth and approach to the lunar surface.

Prior to landing, Odysseus was expected to survive about ten days before the moon’s rotation shifted the sun below the horizon, exposing the spacecraft and its electronics to the deep cold of space.

It is not yet known how many of the experiments that are on board Odysseus can be conducted and return data in that time frame given the lander’s sideways stance and communications bottleneck. That includes a telescope that was built by Canadensys for the International Lunar Observatory Association, a research group based in Hawaii that aims to use the moon as a platform for astronomers.

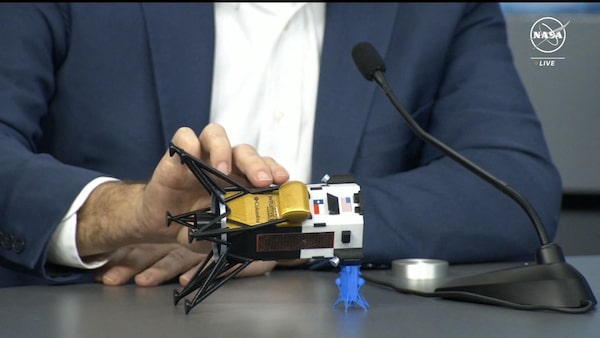

This frame grab from Nasa, shows Intuitive Machines CEO Steve Altemus holding a model of Odysseus to show its position on the side during a press conference at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas on February 23, 2024.Supplied/Getty Images

On Sunday, Dr. Sallaberger said initial indications suggested that the telescope, which is fixed near the top of the 4.3-metre-tall lander, is not directed skyward as planned.

“We’re fearful that it might not be pointing towards the stars, but rather at the surface,” he said.

Odysseus touched down on Thursday after a seven-day journey that began with its Feb. 15 launch aboard a Space X rocket at Florida’s Cape Canaveral. It is the first commercial spacecraft to soft-land on the lunar surface and the first American mission to do so since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Along the way, the lander’s flight team faced a variety of challenges including the discovery that a laser range finder built at the British facilities of MDA, Canada’s largest aerospace company, could not be used to determine the altitude of the spacecraft above the moon.

The cause was an electrical lock that prevents the laser from firing inadvertently during testing as a safety feature. At a news briefing in Houston on Friday, Intuitive Machines flight director Tim Crain said that his company had not deactivated the lock before launch and that there was no way to do so remotely.

Mike Greenley, MDA’s chief executive officer, said that the flight team immediately reached out to MDA when they realized there was a problem.

“The teams were able to share real-time telemetry from the sensor in space so that they could be able to quickly diagnose the issue,” Mr. Greenley told The Globe and Mail.

During the briefing, participants described how flight controllers had to rapidly rewrite software for the landing sequence, substituting the MDA range finder with a NASA-built experimental lidar system that happened to be on board Odysseus as a technical demonstration.

The substitution worked but it also meant that a device called EagleCam, which was to have been ejected seconds before the landing in order to capture images of Odysseus touching down, had to be taken offline.

“If you think back from Apollo days, there wasn’t one mission that went absolutely perfectly, so you have to be adaptable, you have to be innovative and you have to persevere, and we persevered right up until the last moments,” said Steve Altemus, a former NASA engineer and the chief executive officer of Intuitive Machines.

During the briefing, the company revealed how close the spacecraft came to disaster on its way to setting down on the lunar surface – a feat that has previously defeated all private entities as well as some of the countries looking to establish a presence on the moon.

Odysseus began its descent travelling at about 40,000 kilometres an hour and had to shed velocity as it approached its intended landing site near the crater, Malapert A.

Data show that the lander was upright until the final moments before it came to rest. However, as it descended vertically it was also travelling somewhat horizontally, relative to the surface, at about walking speed, Mr. Altemus said. This accounts for why it may have ended up tipped on its side if one of its legs struck an obstacle just before the spacecraft came to rest, he added.

Despite tripping over the threshold, the mission has unquestionably made history as the first of several lunar landings planned by various companies in the next few years.

“It’s an expensive enterprise, but it continues to be increasingly achievable and affordable, which means that there’s a business opportunity there,” Mr. Greenley said.