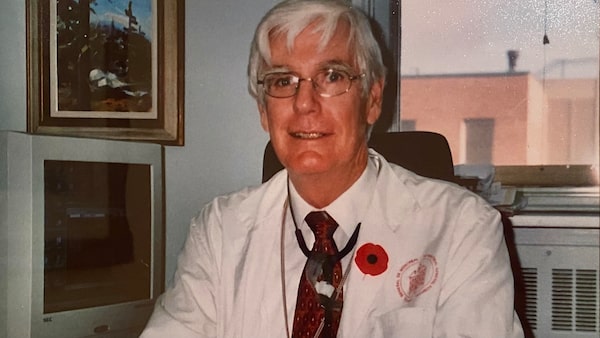

Dr. Robert Gardiner may have been shy, but he never shied away from public service. 'There wasn’t a committee that he wasn’t on,' his son David said.Supplied

When Robert Gardiner was director of the Division of Endocrinology at Montreal General Hospital, beginning in the 1970s, his colleagues knew they could count on him to be kind to all types of patients.

That’s why Ann Macaulay, a Montreal family physician who provided primary care to the Kahnawake community south of the city, never hesitated to refer her Mohawk patients to Dr. Gardiner. “He was very respectful, which was not true of all consultants in those days,” Dr. Macaulay said. “Some of them were quite racist. I felt very safe referring patients to him.”

Dr. Macaulay felt equally comfortable asking Dr. Gardiner for advice about the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Program (KSDPP), a groundbreaking project that she, the late Mohawk physician Louis T. Montour and other community members and academics founded to tackle high rates of Type 2 diabetes in Kahnawake.

As leader of the diabetes strategy at the philanthropic Lawson Foundation, Dr. Gardiner helped steer the charity’s focus toward treating and alleviating diabetes among Indigenous and other underserved communities.

Dr. Gardiner died at his home in Kingston on Jan. 19, one day before his birthday, after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. He was 85. Dr. Gardiner was a former president of the Canadian Diabetes Association (now Diabetes Canada) and a clinician-scientist whose research focused on alleviating the ill effects of diabetes, particularly on patients’ sight.

“He always worried, not only at the Montreal General Hospital, but throughout Canada, about the care for diabetic patients,” said David Mulder, a former chief surgeon who worked alongside Dr. Gardiner at Montreal General, now part of the McGill University Health Centre.

Robert John Gardiner was born on Jan. 20, 1938, in Kingston. The only child of Irene and Arthur Gardiner, he was named after his physician grandfather. His father left to fight in the Second World War when Robert was a toddler.

A precocious child who started school early and later skipped a grade, he graduated at the top of his medical school class from the University of Western Ontario (now Western University) in London in 1961. Endocrinology was a hot field in London, where Frederick Banting was practising and teaching in 1920 when he conceived of the idea that led to his discovery of insulin.

A few years before Dr. Gardiner graduated from medical school, on New Year’s Eve of 1957, a friend set him up on a blind date with Connie Lawson. She was the granddaughter of Ray Lawson, a London businessman who earned his fortune making druggists’ labels, boxes and cigarette cartons, and served as Ontario’s lieutenant-governor from 1946 to 1952.

Connie recalled thinking her future husband was, “pretty special,” on their first night out, a roving dinner party that ended at HMCS Prevost, a naval reserve base in London. The pair greeted 1958 together and stayed together for good. They were married for 63 years.

Dr. and Ms. Gardiner had three sons, Timothy, David and Christopher, and nine grandchildren. The family spent summers at the Gardiner family cottage on Devil Lake, north of Kingston, and skied in the Laurentians in winter. Dr. Gardiner was home most nights for a punctual 6:30 p.m. family dinner. A quiet and reserved man, Dr. Gardiner enjoyed losing himself in the New England Journal of Medicine or the occasional spy novel, according to David Gardiner, his middle son.

Dr. Gardiner may have been shy, but he never shied away from public service. “There wasn’t a committee that he wasn’t on,” David said. Sorting through his late father’s pins after his death reminded David of the many organizations his father led, from the Montreal Curling Club to committees at his beloved Anglican Church, where his sons sang in the choir.

But Dr. Gardiner’s highest commitment was to people with diabetes. As president of the Canadian Diabetes Association from 1980 to 1982, “he was one of the first Canadian advocates to warn that diabetes was an epidemic waiting to happen,” said Timothy Gardiner, Dr. Gardiner’s eldest son.

Dr. Gardiner used his influence at the Lawson Foundation, a philanthropic organization funded by his wife’s family, to expand the charity’s work on other community-based projects. At a regular meeting of Lawson grant recipients, Dr. Macaulay explained how the diabetes prevention program in Kahnawake was carried out by researchers working in full partnership with the community, a model that was rare at the time. Dr. Gardiner embraced the concept and made community partnerships a requirement for all future Lawson grants.

“He was the kind of doctor you’d always want for yourself,” Dr. Macaulay said.

You can find more obituaries from The Globe and Mail here.

To submit a memory about someone we have recently profiled on the Obituaries page, e-mail us at obit@globeandmail.com.