Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland play with children at a daycare in Brampton, Ont., on March 28 before announcing a new child-care deal with Ontario. The deal clears the way for a nationwide network of publicly funded daycares, following in the footsteps of Quebec.Carlos Osorio/Reuters

Bonus podcast • What’s next for $10-a-day child care? The Decibel explains

Mathieu Lacombe has been Quebec’s Minister of Families, responsible for the province’s huge network of daycares, since 2018 – more than three years now. So he sounds a little surprised to admit that, after all this time, none of his counterparts in other provinces have asked to meet him.

The rest of the country is about to embark on an experiment that Mr. Lacombe knows a little bit about. The federal government’s $10-a-day daycare program, which every province has now signed on to, is based on Quebec’s model of heavy subsidies, low fees and theoretically universal access. When it comes to child care, the rest of Canada is about to look a lot more like la belle province.

The last two decades of daycare policy in the province offer many lessons about childhood development, women in the work force, data collection and quality of care – many of them surprising, and some of them likely to reshape Canadian society in the coming years.

In other words, it might be time for enterprising bureaucrats from Victoria to St. John’s to give Mr. Lacombe a call. If they asked him for tips about how to run a provincial childcare network, and how not to, he said, “I’d have many to share!”

Quebec's Families Minister, Mathieu Lacombe, holds sons Justin and Thomas as he is sworn in at the National Assembly in 2018.Jacques Boissinot/The Canadian Press

Quebec’s daycare system is almost as old as the 33-year-old minister himself and has developed slowly, in fits and starts, with many detours along the way. One of the first things experts on the province’s experience are likely to say, by way of advice, is to expect a long road.

“It’s impossible, overnight, to have a fully functioning system,” said Catherine Haeck, a researcher at the University of Quebec at Montreal.

The Parti Québécois launched subsidized daycare in 1997, charging $5 a day for government-funded spots. At first the program only covered four-year-olds, before progressively expanding to cover children from birth by the year 2000.

The network of providers grew fast in the following years, but not fast enough to keep up with skyrocketing demand. By the mid-2000s, parents faced long waitlists.

An austerity-minded Liberal government, led by Jean Charest, tried to solve the problem and cut costs by increasing the tax credit for using for-profit garderies.

That has left Quebec with a multitiered system that has enough space but faces major divides in quality and accessibility, argued Mr. Lacombe. Allowing for the expansion of private daycare, he said, was the “biggest mistake the Quebec government committed in the last 25 years.”

Quebec daycare by type

Per cent (number of places)

Home based

(subsidized)

Non-profit

daycare

centres

(subsidized)

Private

(subsidized)

23%

(66,240)

17%

(47,789)

Private

(non-

subsidized)

35%

(98,468)

25%

(70,004)

July 31, 2021

the globe and mail, Source: Quebec’s Ministry

of Families

Quebec daycare by type

Per cent (number of places)

Home based

(subsidized)

Non-profit

daycare

centres

(subsidized)

Private

(subsidized)

23%

(66,240)

17%

(47,789)

Private

(non-

subsidized)

35%

(98,468)

25%

(70,004)

July 31, 2021

the globe and mail, Source: Quebec’s Ministry

of Families

Quebec daycare by type

Per cent (number of places)

Home based

(subsidized)

Private

(subsidized)

Non-profit

daycare

centres

(subsidized)

23%

(66,240)

17%

(47,789)

Private

(non-

subsidized)

35%

(98,468)

25%

(70,004)

July 31, 2021

the globe and mail, Source: Quebec’s Ministry of Families

The most common and popular form of care today is provided by CPEs, or Centres de la petite enfance, autonomous non-profit daycare centres that are heavily subsidized and regulated. They offer spots at $8.70-a-day and must be governed by parent-led boards; a majority of their workers are unionized and and they are generally better paid.

Small home-based daycares as well as other private facilities, which both receive subsidies to charge the reduced fee, together make up another 40 per cent of the system.

The final quarter – more than 70,000 spots – is composed of unsubsidized facilities that can charge whatever they want.

The current provincial government is making a final push to eliminate many of these more expensive places by spending $3-billion to create 37,000 reduced-fee daycare spots by 2025. But even then, nearly 30 years in, Quebec will still have a patchwork system cobbled together from the public and private.

The good news for the rest of Canada is that even an imperfect government-funded daycare network has produced impressive economic returns for Quebec. The boon comes largely from freeing up women to work outside the home.

Working-age Quebec women have one of the highest rates of labour-force participation in the world, at 86 per cent, just behind Sweden and five points ahead of the Canadian average, according to a study by the prominent economist Pierre Fortin.

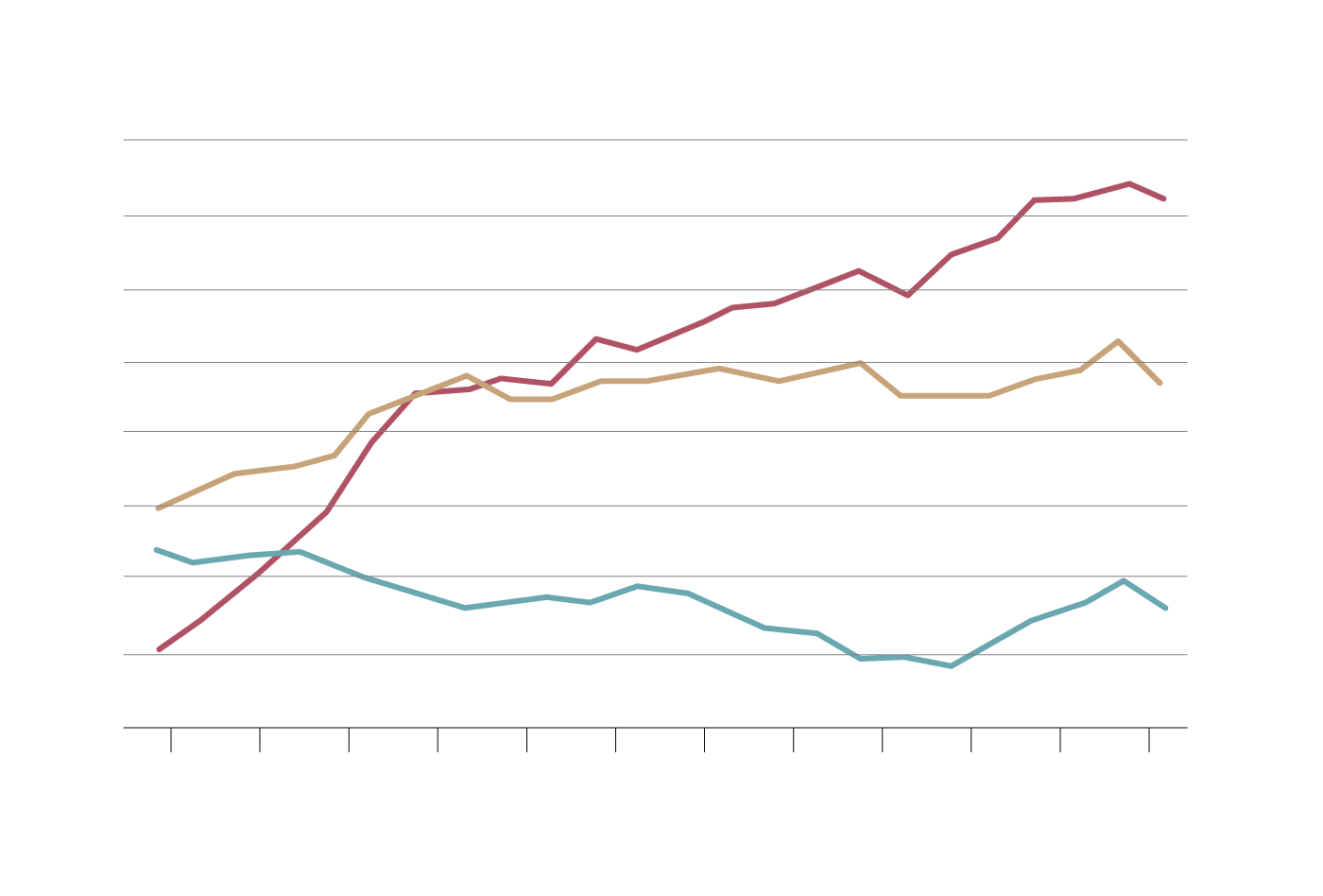

Female labour force participation

Per cent, 25-54 years of age, 1997-2020

88%

Quebec

86

Other

provinces

84

82

80

78

U.S.

76

74

72

1998

‘00

‘02

‘04

‘06

‘08

‘10

‘12

‘14

‘16

‘18

‘20

the globe and mail, Source: Statistics Canada; u.s.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (via a study by Pierre

Fortin, univ.of Quebec at Montreal)

Female labour force participation

Per cent, 25-54 years of age, 1997-2020

88%

Quebec

86

Other

provinces

84

82

80

78

U.S.

76

74

72

1998

‘00

‘02

‘04

‘06

‘08

‘10

‘12

‘14

‘16

‘18

‘20

the globe and mail, Source: Statistics Canada; u.s.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (via a study by Pierre

Fortin, univ.of Quebec at Montreal)

Female labour force participation

Per cent, 25-54 years of age, 1997-2020

88%

Quebec

86

Other

provinces

84

82

80

78

U.S.

76

74

72

1998

‘00

‘02

‘04

‘06

‘08

‘10

‘12

‘14

‘16

‘18

‘20

the globe and mail, Source: Statistics Canada; u.s. Bureau of Labor Statistics (via a

study by Pierre Fortin, univ.of Quebec at Montreal)

The link to daycare is clear and the benefits last throughout mothers’ careers, said Prof. Haeck of UQAM. That means four years of government spending, at most, often produces 30 years of working outside the home (and 30 years of income tax returns).

Because of this fiscal boost, Quebec’s daycare subsidies more than pay for themselves, said Prof. Fortin, who is a professor emeritus at UQAM.

Every dollar the province spent on daycare, he calculated, generated $1.75 in provincial and federal revenue. In 2019 alone, he estimates the overall Quebec economy benefited to the tune of $7-billion in added GDP.

Other provinces should expect that although the fiscal cost of daycare may grow quickly at first as standards are established and workers unionize, it’s no cause for sticker shock, said Prof. Fortin.

Quebec’s government spending growth per space eventually levelled out at less than 2 per cent a year. By 2016, the province’s outlay on daycare – 0.6 per cent of its GDP – was in line with the average for comparable economies.

“It’s expensive – but it’s worth it,” said Mr. Lacombe.

Children in Montreal are led past a strike on Oct. 12, 2021, the day employees at about 400 subsidized daycares – known in Quebec as Centres de la petite enfance, or CPEs – walked off the job. The strikes ended with a deal in December.Paul Chiasson/The Canadian Press

What daycare is worth for children – rather than for women and the economy – is a question that is harder to answer using Quebec’s experience. One thing many observers of the province’s program have seen is that, at the very least, the economics of childcare make it tempting to cut corners on quality.

That is partly because the benefits to the treasury kick in as soon as a child is parked in a space, any space. A woman can work, and pay taxes, so long as Simon or Suzie is being supervised by someone else – even if that supervision consists of nothing more than having children watch cartoons or stare into space.

Parents are also surprisingly bad judges of quality in daycare. In his research, Prof. Fortin found they are apt to keep their children in poor facilities if the price is low or the location is convenient.

That doesn’t mean parents are indifferent to the well-being of their children, just that it’s hard to assess childcare from the outside, in real time. At the age of 1 or 2, Simon and Suzie are unlikely to come home with detailed reports about their éducatrices, unlike older schoolchildren, and the developmental effects of bad daycare tend not to appear until later.

With all these incentives and blind spots tending toward mediocrity, said Kevin Milligan, a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia, “I think there’s a good case to pay attention to quality.”

Children play at a daycare in Coquitlam, B.C.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

It was a pair of studies by Prof. Milligan that did the most to create a perception in the rest of Canada that Quebec daycare led to bad outcomes for children. With colleagues at the University of Toronto and MIT, he found that since the advent of the childcare program, Quebec children experienced greater anxiety and aggression and lower life satisfaction, while running into more problems with the law.

These alarming-sounding results shook up the 2015 federal election when they were released shortly after Thomas Mulcair’s NDP proposed a $15-a-day daycare plan based on the Quebec model. The studies then became the subject of bitter academic controversy when researchers in the province pushed back on the findings.

Because of limitations in Prof. Milligan’s numbers, the story about childhood development turns out to be more complicated, and possibly more encouraging, than initially believed. But even fans of universal daycare acknowledge that the early returns weren’t as strong as hoped, either.

One common critique of the studies was to point out they used all Quebec children as their subjects, rather than just those who attended daycare. Even if that was by design – because only certain kinds of parents send their children to daycare, they don’t constitute a random sample of the population – it left the research open to doubts about whether other factors might be causing the emotional problems.

Another major limitation was the studies’ timeframe. The data Prof. Milligan was using were discontinued by Statistics Canada in 2009. That means we have no real portrait of how Quebec daycare influenced childhood development from that point on, when the system was reaching roughly its current size. “Since the network stabilized, we can’t say anything,” said Prof. Haeck of UQAM. “It’s like you’re learning how to do something, they cut you off, and they evaluate you. … That’s what happened.”

There are reasons to think Quebec childcare improved after 2009, such as better staffing – “They took plenty of people who were well-intentioned but not necessarily well-trained at the start,” said Prof. Haeck – but it is also possible some aspects got worse.

The trend in childhood development was going in the wrong direction when the survey stopped, said Steven Lehrer, a professor of economics at Queen’s University, and it was after 2009 that the lower-quality, for-profit system expanded.

Mr. Trudeau loses a game of tic-tac-toe to a child in Brampton at March 28's media event for the Ontario child-care deal.Carlos Osorio/Reuters

For now, governments probably don’t need to worry that daycare will produce a generation of troubled youth, but they also shouldn’t expect a cohort of baby geniuses. Using statistical models to make certain assumptions about which parents actually sent their children to daycare in Quebec, Prof. Lehrer found the developmental effects were “either zero or slightly negative” – not hugely significant either way.

Still, there are ways of designing a childcare program to maximize the benefits to children. When it comes to quality, Quebec has learned that the details matter. “That’s a message that the rest of the country should know,” said Prof. Fortin. “We don’t just want a place to leave kids every day.”

A successful policy starts with the roll-out, which some believe Quebec bungled. Because older children went into the province’s reduced-fee system first, parents of babies and toddlers raced to secure expensive market-rate spots, said Prof. Lehrer, knowing that they would soon be subsidized down to $5 a day. That gave wealthier families an advantage in daycare access that persists, glaringly, to this day.

A better approach, said the Queen’s professor, would have been to launch a provincial system with a single birth cohort, to avoid this kind of privileged place-holding. Opening the first daycare centres in disadvantaged neighborhoods would be another way to reduce inequality, argued Prof. Haeck, because geographic proximity plays a big role in access.

The value of certain types of daycare is another vivid lesson from Quebec. The more costly and highly regulated CPEs have emerged as the Cadillac of Quebec childcare. Only 4 per cent of non-profit CPEs provided “inadequate” care, according to a 2014 survey, compared to 36 per cent of for-profit garderies.

“At least early on, you’ve got to keep for-profit entities out,” said Rahim Mohamed, visiting assistant professor of International Studies at Centre College in Kentucky, who recently published a study of Quebec daycare and its national reputation in the Canadian Review of Social Policy. “Their model is mass production. You pack kids in, you keep pay low.”

The ideal model for daycare in Quebec, according to a variety of researchers, is a small CPE, with only a few age groups, and streamed by age so that the youngest children get as much attention as older, more active ones. The aptly named éducatrices should be well-paid and college-trained.

Other provinces will forge their own models in the coming years. Élise Bonneville, director of the Collectif petite enfance, an early childhood development advocacy group in Quebec, would like to see the establishment of national roundtables to share lessons from across the country.

Quebec has been a “good laboratory” for the past 25 years, she said. Now it’s the rest of Canada’s turn.

Future of child care: More from The Globe and Mail

The Decibel

Early childhood educators have been leaving the industry in alarming numbers recently, endangering a federal plan to open 146,000 new child-care spots by 2026. Reporter Dave McGinn looks into the reasons for the exodus. Subscribe for more episodes.

More coverage

Explainer: All of Canada is signed on to $10-a-day child care. When will parents see costs go down?

What does the national child-care deal mean for unlicensed operators?

Elizabeth Renzetti: Real men take paternity leave

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.