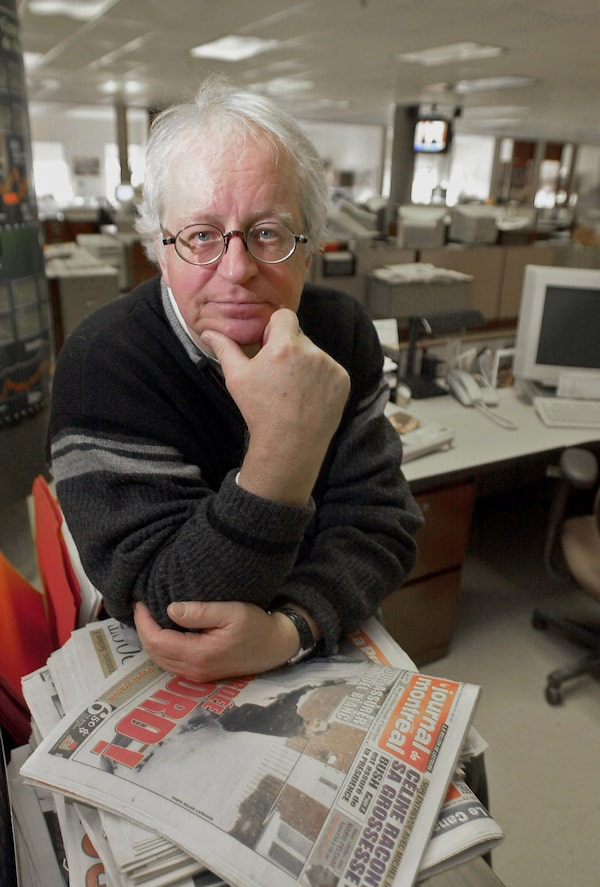

Michel Auger, who was a reporter for Le Journal de Montreal, on Dec. 18, 2000.Andre Pichette/The Globe and Mail

The bullets that struck Michel Auger in 2000 cracked two vertebrae but missed the spinal cord by mere millimetres. They did not kill or paralyze him.

He would enjoy life for two more decades, welcoming another grandchild, resuming his work as a top crime reporter, seeing gangsters go to jail. “We had a 20-year reprieve,” his daughter, Guylaine, said.

Mr. Auger, the Quebec journalist who survived an attempted hit, died Sunday at the age of 76. He had been hospitalized because of complications from a gallstone, his daughter said in an interview.

In a career spanning four decades that included stints at two Montreal dailies, he notched many scoops and was honoured as a symbol of press freedom after the failed attempt to silence him.

A less-known but equally important chapter in Mr. Auger’s career was the five years he worked at the CBC public-affairs television show the fifth estate. His reporting there set the stage for a landmark judgment, the 1982 Supreme Court of Canada MacIntyre decision that ensured public access to search warrant applications.

“Michel and a few others in that era established the legitimacy of investigative journalism as public service [and] created an inspirational record of achievement,” Linden MacIntyre, the former fifth estate journalist who filed that court challenge, told The Globe.

In his memoir, L’Attentat, Mr. Auger said he and the fifth estate had been looking into secret fees that liquor companies paid to political parties, an issue he first heard about while covering the Quebec inquiry into organized crime known as CECO.

In Nova Scotia, the scheme was called toll-gating. The CBC had to sue to access search warrant affidavits filed for an RCMP probe in Halifax, Mr. MacIntyre recalled. “It all started with Michel and his colleagues and their dogged pursuit of the toll-gating story.”

Seeking search warrant papers is now a common tool of enterprise journalism, enabling the media to report on a wide range of law-enforcement actions, whether it is wiretaps of Mafia bosses in Montreal, the police probe into Rob Ford after he smoked crack while mayor of Toronto, or the RCMP handling of this spring’s mass killing in Portapique, N.S.

Mr. Auger’s journalism also left a mark when, starting in 1994, the Hells Angels and rival drug traffickers calling themselves the Rock Machine began a turf war in Quebec where more than 160 people would die.

Stéphane (Godasse) Gagné, a Hells Angels sympathizer turned informant, testified in court that a senior biker pointed out Mr. Auger to Mr. Gagné and said: “That’s the pig. We may do him.”

Detectives identified a suspect in Mr. Auger’s shooting but never had enough evidence to arrest him. Other clues implicated the Hells Angels.

The ensuing uproar added to the pressure on the federal government to help fight the bikers. Ottawa eventually introduced Bill C-24, which amended the anti-gangsterism sections of the Criminal Code, in April of 2001.

Mr. Auger had already returned to work earlier that year. “I had been shot in the back, not the head,” he said.

His hospitalization after the shooting had been a rare pause in his career, except for a sabbatical he took in 1979 to run a bee farm. He thought beekeeping required traits, such as a sharp sense of observation, that were also valuable for reporters.

He was born in Shawinigan, Que., on June 27, 1944, the eldest of the five children of Armand Auger, a factory worker, and Armande Lafrenière, a homemaker.

Young Michel first dabbled in journalism in high school, freelancing columns about his bugle marching band. But the crime world already fascinated him. He got in trouble with his father, who had to be roused from bed after a night shift because the son had skipped school to attend a coroner’s inquest. “His father dragged him home by the ears,” Guylaine said.

Mr. Auger was learning to become a tinsmith but realized journalism was his calling. “He was curious about human nature, human behaviour,” she said.

He started at Le Nouvelliste, a regional paper, then was off to Montreal where he eventually landed in 1968 at a major media outlet, the newspaper La Presse.

His career, from the late 1960s to the early 2000s, coincided with a bustling time in Quebec’s underworld. Montreal’s reigning Mafia clan, the Cotronis, were supplanted by the Rizzutos, whose influence would rival New York’s five Cosa Nostra families. Quebec’s Hells Angels were exceptionally brutal, whether during internal purges or while fighting other bikers. Other criminals were no less colourful, like the nine Dubois brothers, the West End Gang or the crooked union executive André (Dédé) Desjardins.

Crime reporters of that era also became household names. Crotchety, chain-smoking Claude Poirier was the man lawbreakers called to negotiate their surrender to police. Jean-Pierre Charbonneau, a criminology student turned journalist at Le Devoir, covered the mob so energetically that a Mafioso walked into the newsroom and shot him in the arm in 1973.

Mr. Auger was equally famous, acknowledged as a mentor to younger colleagues like Mr. Charbonneau. He was an affable man but, beneath his easygoing demeanour, Mr. Auger was intellectually voracious, persistent and highly competitive.

He cultivated a broad range of sources: detectives, lawyers, criminals, even a snowbird nicknamed Valentino who tracked the whereabouts of Quebec mobsters in Florida. In an interview for the street paper L’Itinéraire, Mr. Auger explained that he rummaged through his old notes on slow-news days to ring up former contacts and keep in touch.

Guylaine Auger remembered her father kept at home index files he compiled on individual bikers while he covered the bloody conflict between the Hells Angels and the Rock Machine for Le Journal de Montréal.

He knew that the Hells Angels kingpin Maurice (Mom) Boucher didn’t like him. A Boucher confidant, the loan shark Bob Savard, had published a photo of Mr. Auger’s old residence in an anti-police magazine.

But despite what had happened to Mr. Charbonneau in 1973, despite a shooting that had wounded the freelance journalist Robert Monastesse in 1995, despite the Hells Angels' murders of two prison guards in 1997, few thought bikers would hurt a reporter of an established paper.

Guylaine said her father didn’t think the intimidation attempts would turn into a murder attempt. “He thought maybe he’d get punched in the face.”

Then, the morning of Sept. 13, 2000, in the Journal parking lot, as Mr. Auger picked up his laptop from his car trunk, he felt like he had been whacked by a baseball bat. He collapsed, hit by six bullets. He caught a glimpse of the gunman running away, then managed to dial 911.

The shooting ended up saving Mr. Boucher’s life. Gérald Gallant, a contract killer for the Rock Machine, had been targeting the Hells Angels and their followers, murdering for example Mr. Savard, the loan shark. Mr. Gallant intended to ambush Mr. Boucher on Sept. 13 but aborted his plan because of the increased police presence following the Auger shooting. Mr. Boucher is currently serving a life sentence for ordering the murder of the two prison guards.

Police later arrested a gunsmith working for the Hells Angels, who had assembled the pistol used in the Auger shooting. Detectives also caught a couple employed at a car-registration service outlet, who looked up drivers' personal information for the Hells Angels, including Mr. Auger’s file.

But the gunman was never caught. Mr. Auger said he wasn’t distressed about it. He once said at a crime-prevention conference that he felt no need to see the suspect punished.

Mr. Auger leaves his spouse, Rina Lupien; his daughter, Guylaine; her husband, Carl Bourcier; and two grandchildren, Nicolas and Amélie Bourcier.

Nicolas is now a reporter for the newspaper La Voix de l’Est. Guylaine said Mr. Auger initially voiced concerns about that career choice but was actually proud, and each morning eagerly looked for his grandson’s articles.