A statue commemorating John J R Macleod is unveiled in Duthie Park in Aberdeen, Scotland, on Oct. 12. The recognition by his hometown comes one hundred years after Macleod was awarded the Nobel prize alongside Frederick Banting for his contribution to the discovery of insulin at the University of Toronto.Neil Gordon/Supplied

The celebration of Canada’s first Nobel Prize for the discovery of insulin at the University of Toronto may well have ranked as one of the most uncomfortable dinners in the history of medicine, based on a meeting of experts revisiting the story a century later.

It was Nov. 26, 1923, and Frederick Banting, a physician and U of T graduate, had recently been named a co-recipient of the prize together with John J.R. Macleod, the professor who had supported and guided his work.

In recognition of the achievement, the two men received honorary doctorates and were feted at a banquet for 400 people in the wood-panelled great hall of Hart House, the university’s splendid new student centre.

But the glowing tributes disguised the seething bitterness that Banting felt toward Macleod – one that had nearly caused him to reject the prize, and that would warp the story of how insulin was discovered for decades to come.

A photo that ran in The Globe, a previous name for The Globe and Mail, the next day shows Banting and Macleod seated at the head table among other dignitaries, as well as Charles Best, the medical student who had worked alongside Banting as a lab assistant.

A banquet was held in the Great Hall of Hart House at the University of Toronto on Nov. 26, 1923, honouring Dr. Frederick Banting and Professor James McLeod, who shared the 1923 Nobel Prize for Medical Sciences for their discovery of insulin. Fifth from left is Dr. Charles H. Best, sitting beside Chief Justice Sir William Mulock (white beard), who is sitting next to Dr. Frederick Banting (fourth from right). Professor J. J. R. MacLeod [John James Rickard MacLeod] is at the far right. Others at the Head table include Canon Cody, Chairman of the Board of Governors, third from right; Sir Edmund Walker, Chancellor, second from right; Hon. W.F. Nickle, Attorney-General, fourth from left; Dean Alexander Primrose, third from left; and Albert E. Gooderham, second from left; and J.G. Fitzgerald, far left.John Boyd/The Globe and Mail

“My guess is that many of the people in the room probably did not know that there was as much tension as there was,” said James Wright, an emeritus professor of pathology at the University of Calgary, in an interview. For those who were aware, he added, “it would have been very awkward.”

Dr. Wright was among the invited speakers at a symposium held at U of T last month. A key theme of the event was the significance of Macleod, a figure so maligned in the original telling of the insulin story that his role remains largely unknown.

“Without Macleod, nothing would have happened,” said John Dirks, a former dean of medicine at the university who co-organized the symposium through the Toronto Medical Historical Club.

The most authoritative version of the story is the one by the late historian Michael Bliss in his highly readable 1982 book, The Discovery of Insulin.

Separated from events by six decades, Bliss drew on documents that had been previously inaccessible or forgotten. His book shattered the myth of Banting and Best as the only two who deserved credit for finding insulin, the crucial metabolic hormone that can bring patients with Type I diabetes back from the brink of death. Yet the myth persists, many at the symposium said.

The discovery begins with Banting, who had an idea about how to isolate a secretion from the pancreas that was suspected to play a role in the body’s ability to digest food. Then a 28-year-old First World War veteran and physician in London, Ont., Banting was no scientist. His interest was partly driven by a desire to escape what had become a dreary and failing practice.

Lacking research experience, Banting was directed to Macleod, an expert in carbohydrate metabolism. They met in November, 1920 when Banting visited the U of T professor in his office and explained his interest in studying pancreatic secretions.

As chronicled by Bliss, they were a study in contrasts. Banting, who was “shy and inarticulate at the best of times,” could not have been at ease in the formidable presence of Macleod, 16 years his senior.

Macleod was skeptical, being familiar with previous efforts by researchers to do what Banting was proposing. But he also recognized the possibility in it.

“If this worked he could see how it could play out and if it didn’t work he could see that something would be learned in the process,” said medical historian Christopher Rutty in an interview. A symposium attendee, he also contributed to a special issue of the Canadian Journal of Health History that focused on Macleod.

Banting was also unsure and tried to get a job as a doctor with an oil drilling crew in the Northwest Territories. When that fell through, he accepted an offer of lab space from Macleod and headed to Toronto in April, 1921 to begin his work. He was aided by Best – a student whom Macleod had previously employed and who had won a coin toss to join the research project as a summer job.

It’s at this point that the myth-making diverges from the facts. According to the former, Macleod, detached and imperious, went to Scotland on holiday, so Banting and Best were alone in what followed. After many failures, the pair succeeded at keeping a dog alive without a pancreas by administering an extract from the surgically removed organ. This paved the way for the extract – insulin – to be used in the first human patient, a 14-year-old boy named Leonard Thompson.

Dr. Charles Best and Sir Frederick Banting pose with one of their lab dogs after the historic discovery of insulin in Toronto in 1921.The Globe and Mail

In reality, as the Bliss account makes clear, Macleod was engaged from the outset. He showed Banting how to perform the surgery and guided the work, maintaining correspondence with the younger doctor while travelling abroad. Upon Macleod’s return, the pair’s promising results spurred him to throw all available resources into the effort. And in December, at Banting’s request, Macleod brought on James Collip, a biochemist who purified insulin for use in people.

But as the implications of the work became clear, the relationship between Banting and Macleod deteriorated. Banting was unconvincing when presenting his data at a meeting of the American Physiological Society at Yale University. Macleod stepped in to address the critics, but his use of the word “we” when describing the research irked Banting, adding to a growing list of perceived slights.

The resentment was magnified in early 1922 during the first tests of insulin as a treatment for diabetes, and as fame and media attention elevated Banting – the Ontario country doctor who had succeeded where others failed.

Later that year, August Krogh, a professor at the University of Copenhagen and a Nobel laureate, met with both Macleod and Banting while visiting Toronto. He concluded that Banting had a poor grasp of the underlying science and would not have succeeded on his own.

While Banting and Macleod received separate nominations for the Nobel Prize the following year, it was the influential Krogh who nominated the two together – for the discovery, and for elucidating insulin’s clinical and physiological characteristics.

When Banting learned that he and Macleod were both named winners, he was furious. Only after the swift intervention of Albert Gooderham, a prominent Toronto businessman and member of U of T’s board of governors, was Banting persuaded to accept the award.

The scale of the breakthrough was certainly what Alfred Nobel had in mind when he created his prize, said Erling Norrby, a professor and former secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences who spoke at the recent symposium.

“A good discovery is one that leads to the explosion of a new field,” he said in an interview.

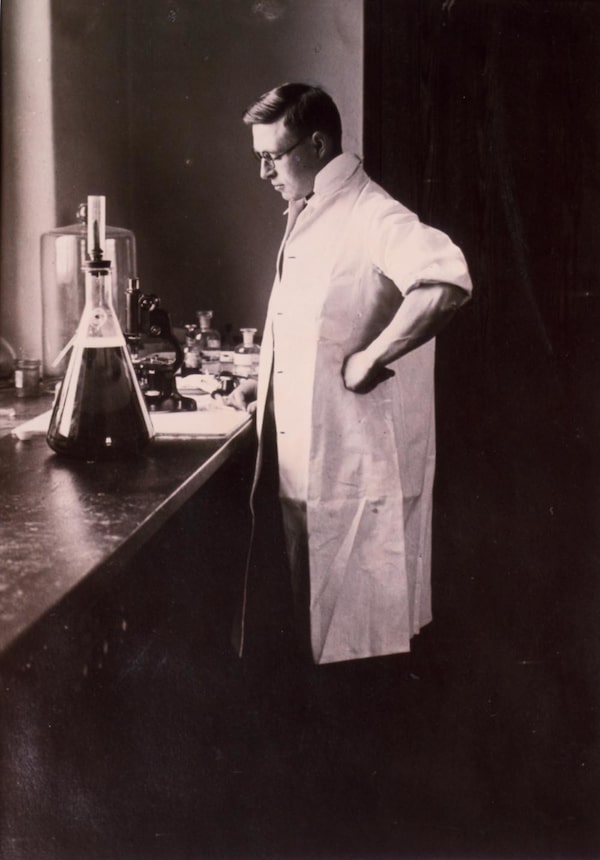

J. B. Collip in a laboratory in Edmonton circa 1927.Supplied

Another symposium speaker, Ken McHardy, who is an honorary senior lecturer at the University of Aberdeen – Macleod’s alma mater – said the discovery was even more than that because it gave rise to the concept of a managed illness.

“There really wasn’t chronic disease until insulin,” he said in an interview, adding that Macleod would have understood this because he helped co-ordinate the initial mass production of insulin.

Yet it’s clear that Macleod suffered from the attacks by Banting and his supporters. Eventually, it deprived U of T of an accomplished scientist and medical educator when Macleod returned to Aberdeen to become a regius professor. By his own account, he left Toronto in 1928 ready “to wipe away the dirt of this city.”

While Banting and Best acquired legendary status in Canadian history, Macleod, who died in 1935, rarely spoke of the discovery, and his place in history faded from view. Michael Williams, a diabetes specialist who was born and trained in Aberdeen and later became Macleod’s biographer, had never heard of his subject till he came across Michael Bliss’s book.

“I cannot imagine the sound of his jaw hitting the floor when he reads this book and finds that someone from his own school and medical school had been awarded a Nobel Prize for discovering insulin,” Dr. McHardy said.

Aberdeen has more recently tried to address the oversight, with the unveiling in October of a statue of Macleod in the city’s Duthie park. During the dinner after last month’s symposium, Dr. Dirks called for a fuller recognition of Macleod and Collip alongside Banting and Best.

Dr. Dirks echoed the words of Lewellys Barker, a physician-in-chief at Johns Hopkins Hospital and U of T graduate who was present at the Hart House dinner a century before: “In insulin, there is glory enough for all.”