Images of Pope Alexander VI circa 1485 and 1495.Hulton Archive/Getty Images/Getty Images

Before Rodrigo Borgia donned the papal tiara in 1492 and became Pope Alexander VI, he’d had multiple mistresses and fathered at least eight children. He favoured debauched parties with dancing prostitutes and used the papacy to enrich his Spanish family.

Upon his death, likely by poisoning, subsequent popes sealed off the Vatican apartments where Pope Alexander and his family had lived, as a prophylactic against the ghosts of his orgiastic reign.

And this is where many biographical entries end, prioritizing titillation over the substance of his rule, which still haunts the world despite the efforts of Vatican ghostbusters.

Abridged accounts of his life tend to exclude the randy pope’s central role in Europe’s heist of the Americas during the Age of Discovery, a mass dispossession of Indigenous peoples that remains foundational to Canadian sovereignty.

Today, the international legal principle called the Doctrine of Discovery holds that Christian nations of Europe legally acquired vast tracts of Indigenous land by making landfall during the Age of Discovery and raising flags, or planting crosses or digging some sod. The doctrine, formulated in the Vatican’s official decrees, known as papal bulls, and developed over the centuries by philosophers, scholars and an influential U.S. Supreme Court judge, has been used to explain how the Crown continues to hold underlying interest in all lands within Canada.

As Pope Francis prepares for his arrival in Canada next week, he faces mounting pressure from the Assembly of First Nations and others to revoke the Doctrine of Discovery. Such a task is well beyond the powers of the Vatican, but the strange history of the doctrine could be said to serve as a warning against underestimating the pope’s influence.

“The story of the doctrine is the story of how you can obtain other people’s land by magic,” said Harry LaForme, who was Canada’s first Indigenous appellate judge before his retirement in 2018. “You just sprinkle these papal bulls and you get it.”

Harry LaForme in October 2018.Mark Blinch/The Globe and Mail

The 15th-century world, according to Pope Alexander VI

Rodrigo Borgia became Alexander VI the same year Christopher Columbus happened upon the Bahamas and returned to Spain bearing parrots, gold, Indigenous prisoners and syphilis. The discovery, as it was then called, raised the prospect of untold riches, but also of war with Portugal, which had developed its own plunderous ambitions.

Previous popes had granted Portugal exclusive right to trade with, and enslave, the people of West Africa. The Spanish Crown wanted assurances from the Vatican that it would not grant the Portuguese the New World as well.

Spain needn’t have worried. Pope Alexander VI was a Spaniard through and through.

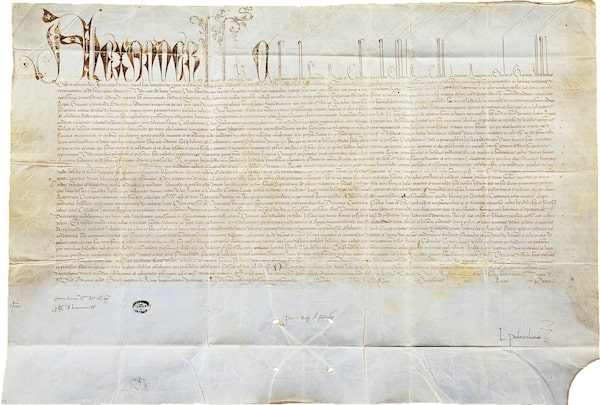

Like a parent dividing cake between petulant children, Alexander VI issued Inter Caetera, a series of papal bulls that drew a vertical line down the middle of the Atlantic, granting Portugal and Spain a hemisphere, or half a cake, each.

Under these Papal Bulls of Donation, any non-Christian lands discovered west of the line went to Spain. Portugal got non-Christian lands east of the line. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas would clarify the boundaries. In practical terms, Spain got the Americas and Portugal got Africa, plus the eastern protuberance of South America, known today as Brazil.

The blue vertical line on the left of this 1502 map marks the boundary agreed to in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.Biblioteca Estense Universitaria

The bulls stated that Portugal and Spain were entitled to the “free power, authority and jurisdiction of every kind” over all non-Christian lands, terra infidelibus, discovered in their respective hemispheres. While the stated intent of the bulls was mass Catholic conversion of Indigenous peoples, conquest and domination were at their core, according to Steven Newcomb, a Lenape-Shawnee scholar and author of Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Christian Doctrine of Discovery.

During a 2013 visit to the General Archives of the Indies in Seville, Spain, Mr. Newcomb convinced an archivist to show him one of the remaining versions of Inter Caetera, written on sheepskin parchment with indelible octopus ink.

Inter caetera Divinae Bull, 1493.M. Seemuller/De Agostini via Getty Images

Beneath glowering portraits of Balboa, Cortez and other Spanish conquistadors, Mr. Newcomb pored over the familiar Latin phrases, many of which he’d memorized over 40 years of researching the doctrine. The archivist flipped over the document. It was mostly blank, but one phrase gave Mr. Newcomb a jolt: “To Win and Conquer the Indies.” The Vatican’s ambitions were revealed.

“There was that domination pattern right from the beginning,” he said. “The entire world order is still premised on this claim of domination.”

Word spread throughout Europe. Soon, other countries wanted in on the rush for spoils. In 1496, King Henry VII of England endorsed John Cabot’s transatlantic voyage “to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.”

In other words, Cabot could claim for the Crown any land Spain hadn’t reached first. “If you go back and look at any of those colonial charters, so-called Crown charters, they are imitating the formula of the Vatican papal documents,” Mr. Newcomb said.

The next few hundred years, highly abridged

The Vatican would eventually clarify that the 1493 allocation of territory to Portugal and Spain only applied to lands known to exist at the time. Anything discovered after was finders-keepers. The ruling prompted France to send Jacques Cartier abroad.

Explorers employed various rites when taking possession of unfamiliar land. Cartier’s crew erected a nine-metre cross on the Gaspé Peninsula.

Jacques Cartier with Cross at Gaspe, Quebec, 1534. Drawing dated ca. 1880-1908.Henri Julien/Library and Archives Canada

Others piled up a few stones. In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert grasped a stick and piece of sod to symbolize the Crown’s possession of Newfoundland.

“That’s the ridiculous, bizarre nature of this whole exercise,” Mr. Newcomb said. “They’ve been able to get away with it because it was just European nations agreeing amongst themselves to abide by those rules – honour among thieves – and the original nations and peoples have not been given an opportunity to respond and point out how utterly ridiculous it is.”

By the 1530s, the Protestant Reformation was in full swing. Rulers and scholars began questioning the legitimacy of Europe’s overseas claims and their papal foundation. In 1533, Charles V of Spain convened a group of scholars to debate the issue. One of them, Francisco de Vitoria, concluded that any claim to the Americas based on papal or monarchical authority was illegitimate.

“He stated that Indigenous peoples have rights and ownership over their land,” said Douglas Lind, a Virginia Tech professor whose research focuses on the philosophy of law. “The people might have universal power to try and convert people everywhere to Christianity, but that doesn’t give the pope the right to designate lands on the basis of discovery.”

Vitoria conceded that unoccupied lands belonging to no one (terra nullius) could be claimed by the first to discover them, but argued that Indigenous people “undoubtedly possessed [their lands] as true dominion, both public and private, as any Christians.”

He reasoned that Europeans in the Americas held a natural right to travel, trade, spread Christianity and partake in communal resources, such as water, but that those rights fell short of any ownership or dominion.

Later philosophers and legal theorists, such as John Locke and Emer de Vattel, would expand on the idea, warping it to suggest that legal possession of land must be accompanied by settlement and cultivation. Vattel, an influential 18th-century jurist, reasoned that Europeans were entitled to take possession of the Americas because the land was vast, with a largely nomadic Indigenous population.

The 1502 map again, showing how the Western Hemisphere was viewed by Europeans.Biblioteca Estense Universitaria

A 1707 map of the Western Hemisphere by Johann Baptist Homann. Nuremburg.Library of Congress

A 1777 map of the Western Hemisphere titled, 'A new map of the whole continent of America: divided into north and south and West Indies with a descriptive account of the European possessions, as settled by the definitive treaty of peace, concluded at Paris February 10th, 1763.'Library of Congress

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 imposed yet another interpretation. It assumed Crown ownership over much of North America and reserved a vast swath for Indigenous groups that could only be acquired by treaty with the Crown. The document offers up a vexing contradiction, simultaneously asserting Crown sovereignty over North America and safeguarding Indigenous land ownership.

By the 19th century, the United States had begun grappling with the question of how it came to possess such broad territory in a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings. In the landmark 1823 Johnson v. M’Intosh case, two people claimed ownership of the same piece of land. One said he had acquired it from an Indigenous tribe, and the other said he had obtained it from the federal government.

It was up to the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall to decide who owned underlying title to the land – the tribe or the feds.

Marshall laid out the principle of discovery. He wrote that the papal bulls and agreements with neighbouring European nations had granted Spain authority to extinguish Indigenous title in the Americas, that European discovery amounted to European title and that only the federal government, not the tribe, had the authority to cede the land in question.

Any other conclusion, Marshall reasoned, would undermine U.S. title to all lands in America and the government’s validity.

“The right derived from discovery and conquest, can rest on no other basis,” he wrote, “all existing titles depend on the fundamental title of the crown by discovery.”

Indigenous people had a right to occupation and possession, he continued, but their rights to complete sovereignty had disappeared.

That old papal magic had re-emerged.

“The court relied on a principle, established through the papal bulls, that European countries had agreed between themselves that they could basically show up, usurp Indigenous sovereignty, assert sovereignty over Indigenous lands and claim ownership,” said Bruce McIvor, who is a lawyer, Manitoba Métis Federation member and the author of Standoff: Why Reconciliation Fails Indigenous People and How to Fix It.

So what does all this have to do with Canada?

The Canadian courts began citing Johnson v. M’Intosh as they developed theories of Indigenous rights that have endured to the present day.

The Supreme Court of Canada’s 1887 St. Catharines Milling and Lumber decision leaned heavily on Johnson v. M’Intosh in arguing that Indigenous land rights were “personal and usufructuary.” That is, they could use it, but the Crown owned it.

That view lasted in Canada until a series of Supreme Court decisions established and clarified aboriginal title, starting with the 1973 Calder decision and ending most recently in the 2014 Tsilhqot’in ruling. Aboriginal title has come to mean the occupation, use and control of ancestral lands. But Chief Justice Marshall’s imprint remains.

Frank Calder, Chief of Chiefs of the Nisga'a Nation and British Columbia's first Indigenous cabinet minister, talks to media in Ottawa in February 1973 after meeting with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chretien.CHUCK MITCHELL/The Canadian Press

Chief Roger William, right, of the Xeni Gwet'in First Nation. He is flanked by chiefs and other officials as he pauses while speaking during a news conference in June 2014, after the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in favour of the Tsilhqot'in First Nation.DARRYL DYCK/The Canadian Press

The Tsilhquot’in decision says that the Tsilhquot’in people lost “radical or underlying title” to their land when European sovereignty was asserted. The statement cites an earlier Canadian Supreme Court decision that, in turn, cites Johnson v. M’Intosh and Marshall’s discovery principle.

“It’s the same move as the papal bull 500 years earlier,” said Senwung Luk, a partner at Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP, a firm focused on Indigenous law. “It’s not saying the land belongs to the pope, but it is saying that sovereignty is rooted in European power.”

The United Nations, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission have all denounced the doctrine and called on governments to remove the concept from laws and policies.

But how?

In recent years, scholars and jurists have labelled the Doctrine of Discovery a legal fiction, a conjuring, a story – but not a law. History shows it has morphed several times under the auspices of popes, monarchs, philosophers and judges. It is ephemeral, not explicit, yet it remains baked into Canadian property law and answers the question of why the Crown owns Canada.

“The very legitimacy of Canada is based on this principle,” Dr. McIvor said. “Every time someone in Canada sells property and wrings their hands in glee over all the money they’ve made, they are participating in the Doctrine of Discovery. Every resource development, every pipeline – that’s all based on the Doctrine of Discovery.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has said Canada’s reliance on the Doctrine of Discovery should be replaced with a duty to renew or establish treaties in way that would recognize Indigenous laws and traditions. The Supreme Court has said much the same.

Felix Hoehn, a professor of property law and administrative law at the University of Saskatchewan, has written that the Supreme Court could disavow the idea of limited aboriginal title grounded in the Doctrine of Discovery and direct Ottawa to fulfill a legal and moral duty to reconcile sovereignty through negotiation. “Crown sovereignty is constitutionally flawed until there’s a treaty,” Dr. Hoehn said in an interview.

Mr. LaForme, the retired appellate judge, has compared Indigenous law to an ailing tree that will rot unless the “false discovery doctrine and all that grew out of it” are discarded.

And it can’t hurt to enlist Pope Francis in the effort.

“Let’s see what kind of magic he has left,” Mr. LaForme said.

Harry LaForme.Mark Blinch/The Globe and Mail

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.