Tim Coochey indicates the height of the floodwaters that damaged the basement of his Montreal-area home. Mr. Coochey's was one of the many homes damaged during the flooding of May, 2017.Dario Ayala/The Globe and Mail

Tim Coochey had no idea how much water was coming his way. As the St. Lawrence River swelled in May, 2017, the resident of the Montreal borough of Pierrefonds-Roxboro assumed the home he’d bought a quarter-century earlier was safe; after all, the river was more than 250 metres away, and the neighbourhood’s drainage infrastructure had been upgraded considerably since the last notable flooding, in the 1970s.

But as the river rose, storm sewers began working in reverse. His street flooded. Mr. Coochey watched in shock as his driveway, which slopes toward his house, filled with water in a matter of minutes and spilled over the makeshift barricade in front of the garage door. He told his family to abandon the house.

“I didn’t even know it was a flood zone,” Mr. Coochey said. “Only now am I finding out that my particular street was basically swamp, which they backfilled. And then they built houses on it.”

Those floods could have played out differently had Mr. Coochey, his neighbours and their civic officials better understood the situation with the help of flood-risk maps.

Tim Coochey in the driveway of his home in Pierrefonds.Dario Ayala/The Globe and Mail

Flood maps – cartographic depictions of areas that are likely to flood under certain conditions – are invaluable sources of information for homeowners and civic officials. In the United States, England and France, one can enter a postal code into a government website and quickly assess a property’s susceptibility to flooding. Had Mr. Coochey possessed such information, he could have taken steps to protect his property – or never purchased the home in the first place. Various studies have determined that every dollar spent on flood prevention is worth many times that amount in property replacement costs.

Yet the vast majority of Canadians do not have easy access to such maps. Partly due to government cutbacks – and the reluctance of municipalities to discourage development – all too often the best many homeowners can do is visit a local government office and dust off a decades-old relic intended for engineers or hydrologists.

Professor Jason Thistlethwaite and colleagues at the University of Waterloo recently completed a study of almost 700 Canadian flood maps. “The results are not impressive,” he said. Many were old, few had been digitized and most were not publicly accessible.

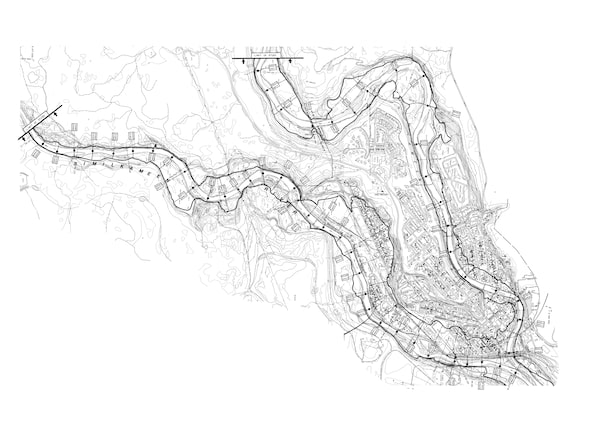

Detail of a flood-risk map for a neighbourhood in Fredericton, N.B., currently available on a provincial website. It was prepared in the late 1970s using data available at the time. New Brunswick is currently creating new flood-hazard maps for inland areas, a process expected to be completed by mid-2020.Environment Canada/New Brunswick Department of the Environment

And for as many as a third of Canadians living in flood-prone areas, there are no flood maps to consult. Mr. Coochey is one of them. The Globe and Mail asked his municipal government for flood maps of his neighbourhood. The municipality said such a request would “disrupt the flow of work of the borough office,” but promised to respond within a month. When it did respond, two months later, it said it didn’t have any such maps.

Little wonder, then, that rising floodwaters catch so many Canadians off guard. According to a 2016 estimate by analytics firm LexisNexis Risk Solutions, there are 8.6 million residential addresses in Canada. More than a fifth of those – 1.8 million – are susceptible to flooding. By another estimate, as much as 10 per cent of Canada’s population lives in high-risk flood zones. However alarming that may seem, the bigger problem is that nearly all of those at risk don’t know it. A 2017 survey of 2,300 homeowners by the University of Waterloo found that just 6 per cent of respondents realized they lived in designated flood-risk areas.

That ignorance often leads to bad decisions. Without flood maps, prospective home buyers may unwittingly purchase at-risk homes. And they may fail to take protective measures, such as installing sump pumps, regrading their properties or purchasing the right kind of insurance.

This week’s floods in Quebec and New Brunswick are the latest reminder of what happens when communities fail to account for the risks as they grow. Entire neighbourhoods may be developed in harm’s way, resulting in extensive damage and financial loss for homeowners, insurers and government disaster-assistance programs.

Related: Residents urged to stay alert as flooding affects homes across Quebec

The federal government is well aware of the situation. “Canada lacks effective flood hazard maps, which are considered essential risk assessment tools,” according to a 2017 report published by Public Safety Canada. But remedying the situation would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and might take a decade. And few governments in Canada seem willing to accept the challenge.

A flood of forgetfulness

While maps cannot guarantee better flood management, they are a crucial start. Canada has largely forgotten how to draft them. The irony is that we were once considered a world leader.

In 1975, Environment Canada introduced the Flood Damage Reduction Program (FDRP). Organized as a series of deals between Ottawa and provincial and territorial governments, its cornerstone was producing flood-risk maps for urban areas. All provinces and territories participated except Prince Edward Island and Yukon.

Ottawa’s motives were not entirely altruistic. A few years earlier it had introduced the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements, a cost-sharing program with provinces for mopping up after natural disasters. The scheme had been stung by a series of costly flood claims. Ottawa’s goal with the new program was to wash its hands of people who insisted on building in high-risk areas. In the hopes that they would inform better land-use planning, the new maps were to be widely disseminated.

By most accounts, the effort paid off. A report by the Government of Saskatchewan found that participating communities such as Regina and the town of Lumsden, in the Qu’Appelle River valley, had used that information to take a variety of flood-prevention measures, from diking to regulating land use in floodplains, that “greatly aided” them later. Had Lumsden not constructed its dikes in the late 1970s, the report estimated, it would have suffered $140-million in property damage during the serious floods of 2011; instead, it suffered “minimum” damage.

The FDRP wasn’t an unqualified success. Some communities continued making bad decisions; one study found that development continued in defined floodplain areas in Montreal, for instance. “The information may have been there, but there was no teeth or enforcement,” Prof. Thistlethwaite said.

Nonetheless, almost 1,000 communities were mapped and their floodplains identified. One 1995 assessment published in the Canadian Water Resources Journal concluded the FDRP had been “extremely successful in identifying urban flood risk areas across Canada and in redirecting damage-prone development away from flood risk areas.”

So highly regarded was the program, University of Western Ontario geography professor Dan Shrubsole said, that countries in Europe and the Caribbean requested Environment Canada’s assistance in mapping their own floodplains.

But then the FDRP fell victim to budget cuts, and the federal government eventually cancelled it in 1996. Provinces were left to their own devices. Wealthier provinces, including Alberta and Ontario, continued mapping, albeit no longer to common standards. Activity in the Maritimes, meanwhile, ceased almost completely.

Today, Canada is among a minority of members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that lack a national floodplain mapping program. Many communities continue to rely on FDRP-era maps. MMM Group, a consultancy hired a few years ago to assess the situation, found that half the maps still in use are between 18 and 40 years old.

Considered cutting-edge in their day, the FDRP maps have not aged well. Most of them feature a single line delineating the area affected by a specified regulatory flood level. (Actual flooding risk is, of course, more nuanced.) And many maps were of such coarse resolution that they are of little use to property owners seeking to understand the risk of flooding on their properties.

An even bigger problem is that many of Canada’s flood maps have outlived their usefulness. With a changing climate, relying on decades-old data and assumptions about rainfall and storm surge is a dangerous proposition. Changing landscapes must also be taken into account. When loggers, wildfires or pine beetles destroy large swaths of forest, more water tends to run off into rivers more quickly. Meanwhile, far away from watercourses, increased development and the destruction of wetlands can fundamentally alter where water goes after heavy rainfalls.

A 1995 flood map of the Similkameen River at Princeton, B.C.Environment Canada, B.C. Ministry of the Environment

Blind in British Columbia

Neil Peters, a water resource engineer, witnessed Canada’s increasing blindness to flood risks. When he was hired by the B.C. government in 1987, the province had already paid for dozens of flood maps out of pocket and had about 45 people working full time on flood management. It joined the FDRP and mapped a total of 89 areas prior to its cancellation.

But British Columbia’s flood-mapping expertise was already in gradual decline. After the FDRP’s demise, the province downloaded most of the responsibility for flood mapping and management to municipalities, including decisions regarding development on floodplains. Tamsin Lyle, principal at Ebbwater Consulting, said the province henceforth contributed very little funding or expertise to flood-mapping efforts. “The municipal governments were pretty much left on their own,” she said.

The problem is that municipalities have powerful disincentives for regulating floodplain development. After all, they rely on property taxes for revenue and face “a lot of pressure from developers and others to promote development of the city,” said John Pomeroy, a geography professor at the University of Saskatchewan. “And where do people want to live? Humans want to be on the water.”

What’s more, floodplain maps are costly to produce; according to a 2017 report by the B.C. Real Estate Association, communities in the province struggled “to find funding sources for floodplain mapping projects.”

The result of B.C.'s decision was predictable. “There was very little mapping done” by B.C.'s municipalities after the FDRP’s cancellation, Ms. Lyle said. Surveying the state of the province’s flood maps in 2015, Ebbwater found that the median age was 26 years.

More alarmingly, much of the populous Lower Fraser Valley still hadn’t been mapped or was served by maps dating from the 1960s. Ebbwater estimated that more than 300,000 people live on the floodplain in Delta, Coquitlam and particularly Richmond. According to a report published this year by the province’s Auditor-General, the Lower Mainland is expected to flood more often; owing partly to the changing climate, flood levels previously expected just once every 500 years may now be expected every 50 years.

By the time Mr. Peters retired in 2016, B.C. had just eight full-time-equivalent professionals working in flood management, down from 45 three decades earlier. Asked how much development had taken place on B.C.'s floodplains, he said it had clearly happened but he couldn’t quantify it. “I really don’t have a good handle on that. I don’t think anybody does.”

The price of ignorance

While Ottawa successfully downloaded responsibility for flood mapping to lower levels of government, it still had to pay for much of the resulting bad decisions.

Payments from the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements, now administered by Public Safety Canada, are triggered when damages exceed certain thresholds per capita of population, rising to as much as 90 per cent of costs. The more expensive the disaster, the more Ottawa pays. Canada’s flood-mapping dark age coincided with skyrocketing payments for flood damage – of a magnitude far greater than what prompted the FDRP in the first place.

There’s every reason to believe damages will continue to escalate. In 2016 the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated that the DFAA could expect to pay out an average of $673-million for flooding alone during each of the following five years.

It’s difficult to quantify how much of the mounting costs can be attributed to bad planning decisions, because the evidence is mostly anecdotal. Prof. Thistlethwaite points to a 2013 storm in Toronto that caused widespread power outages “mainly because they had transformers in low-lying areas that flood.” But other factors are also driving up the damage costs, including a changing climate and the fact Canadians have more valuable belongings – everything from big-screen TVs to luxury cars – than in the past.

Asked to hazard a guess, Mr. Pomeroy estimated the federal government saved between $40-million and $60-million by cancelling the FDRP. “But I think it’s cost us billions since then,” he said.

Stung by these rising costs, governments are once again seeking to download responsibility – this time directly to homeowners. In 2015, insurance for overland flooding became available to Canadian homeowners. Daniel Henstra, an associate professor in the University of Waterloo’s political science department, said both Ottawa and some provinces are eager to withdraw eligibility for disaster assistance from areas where that insurance is now offered. Indeed, this week Quebec Premier François Legault proposed capping assistance to homes that flood repeatedly.

Local resident Lyne Lamarche walks through floodwaters near her home in Gatineau, Que., on April 23, 2019.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

The problem, according to Prof. Henstra, is that most Canadians can’t assess the likelihood their property will wind up under water. “If governments are going to start cutting off people’s eligibility for disaster assistance, they’d better make that risk knowable,” he said. "And right now, it’s not.”

The insurance industry, on the other hand, is quickly amassing property-level risk data. A few years ago, the Insurance Bureau of Canada hired LexisNexis Risk Solutions and JBA Risk Management to create a national flood-risk model. JBA collected data on snow cover, rainfall, historical river levels, land cover, terrain and flooding across Canada to produce its own flood models and maps. LexisNexis used that to build a software product underwriters can use to decide whether to offer flooding insurance to homeowners and at what price. While imperfect, the insurance industry’s data are far superior to what’s available to the Canadian public – and the quality continues to improve.

Moving toward renewed national flood mapping

Ottawa has in recent years made tentative steps toward addressing the problem. Public Safety Canada took a hesitant early step by introducing its new guidelines for floodplain mapping. And in 2015 it introduced the National Disaster Mitigation Program, a $200-million five-year initiative intended to fund some flood mapping and flood-risk assessments.

Ms. Lyle of Ebbwater said the federal program prompted a recent uptick in flood mapping activity in B.C. But the maps she’s seen often don’t meet existing guidelines, which she already regards as weak. And one legacy of the FDRP’s dissolution is a dearth of professionals with adequate experience and training. She’s afraid much of the new funding will be wasted. "There’s a lot of very poor mapping being done,” she said.

Prof. Henstra and Prof. Thistlethwaite recently published a paper urging the federal government to follow Australia’s example by creating a national repository of Canada’s existing flood maps. But that’s just a stopgap measure: Canada’s longer-term objective, they argue, should be to map all of Canada using modern techniques and uniform standards – all with a view to reducing risk.

Thanks to technological advances, modern flood maps can accomplish much more than their predecessors. Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) can produce high-resolution elevation data that can be used to simulate a multitude of different flooding scenarios. Using modern geographical information systems (GIS), it’s now relatively straightforward to combine flood-hazard information with inventories of buildings and other infrastructure, allowing users to understand what’s at risk.

Digital maps can be published online as interactive tools, maximizing their reach and usefulness. Residents of England, for example, can obtain detailed information about their flood risk on this national website.

Screen capture of an interactive map showing flood risk in Bristol, England.

Catching up to Canada’s peers would not be cheap. A 2014 estimate by the MMM Group estimated each square kilometre of floodplain mapped to modern standards would cost between $7,500 (for rural areas) and $10,500 (for cities). After mapping additional floodplains for which maps are not available, the national tab would come to $365-million. It could take as long as a decade.

But that should be weighed against the costs Canadians have already paid – and will continue to pay – for not knowing where floodwaters will go.

It’s a price Mr. Coochey knows all too well. He spent almost two years and tens of thousands of dollars repairing his basement on evenings and weekends. With Pierrefonds at risk of flooding again, he and his neighbours hauled truckload after truckload of sandbags over the weekend to his street to erect new barriers. He’s watching river-level data and video footage of upstream dams nervously.

There still aren’t any flood maps for his neighbourhood, although he believes new ones are being drawn up. But they didn’t arrive soon enough for the neighbours who moved into a townhouse across the street a few months ago.

“When we started fixing up for the floods, they come up and they say, ‘What the hell is going on?’ We’re going, ‘Well, we’re preparing for another flood,’ ” he said.

"They go, ‘Another flood. What flood?’ ”

How you can help fill the data gaps

The gaps so far

The Globe and Mail has uncovered myriad data deficits, culled from dozens of interviews, research reports, government documents, international searches and feedback from our own newsroom. Here's a list of what we found, which we'll be adding to as the investigation continues.

Globe and Mail reporters will continue to collect and report on data gaps that affect Canadians. If you have one in mind, please submit a description of it. Data gaps will be investigated by our reporters before they are published.