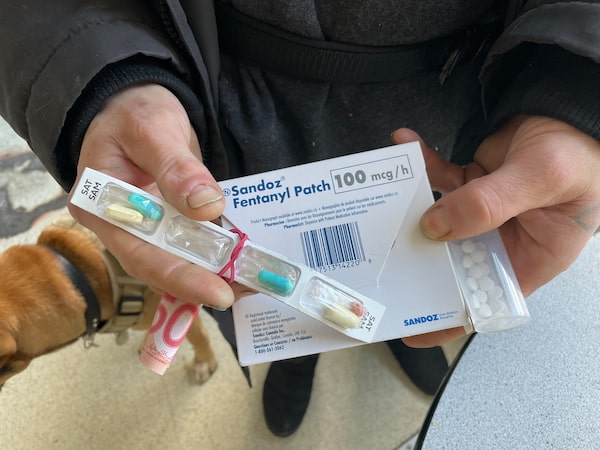

A patient displays medications and a $50 cash kickback that a pharmacy employee delivered to him, in violation of College of Pharmacists of B.C. bylaws, on Feb. 6 in Vancouver. The man told The Globe and Mail that the pharmacy pays him $50 per week and does not change his fentanyl patches, as ordered by his doctor.Andrea Woo/The Globe and Mail

A 40-year-old man leans against a windowsill in his Vancouver single-room occupancy hotel, awaiting a delivery of medication from a pharmacy. A drug user for half his life, he is now prescribed fentanyl patches that adhere to the skin, along with tablets of the opioid medication hydromorphone, to stave off withdrawal symptoms.

A man walks up and exchanges brief pleasantries as he reaches into the black delivery bag slung over his shoulder. He pulls out a box of fentanyl patches, a container of hydromorphone tablets and pain and antipsychotic medications, handing them to the SRO tenant.

Taking a quick look around, the man reaches back into the bag a second time, pulls out a rolled-up $50 bill and hands that to the tenant, too. The man then turns on his heel and leaves.

The delivery man, whose actions were observed by a Globe and Mail reporter, is part of a kickback scheme perpetrated by a number of B.C. pharmacies. Prohibited cash incentives are paid to patients to fill their prescriptions at their locations and recruit others to do the same, maximizing the amounts that the pharmacies can bill the province’s publicly funded drug plan. The pharmacies appear to target economically vulnerable patients – largely those with substance use disorders.

The Globe spoke to 28 doctors, nurses, pharmacists, patients and social-service providers to learn the scope of the practice and how such pharmacies covertly encourage patients to participate. Among them, two doctors, two pharmacists and several patients independently revealed the names of dozens of pharmacies alleged to offer kickbacks, including locations in Vancouver, Burnaby, Surrey, New Westminster and Victoria.

The Globe is not identifying many of the sources, including doctors and pharmacists who said they were worried about professional repercussions, and patients who were concerned that they would lose access to medications.

The College of Pharmacists of B.C. explicitly prohibits pharmacies from offering inducements on costs paid by PharmaCare. In 2016, the regulatory body enacted bylaws banning pharmacies from offering incentives such as cash, coupons and loyalty points on any prescription medication, prescribed medical supplies or for pharmacy services.

The Globe has reviewed correspondence from, and spoken with, complainants who have formally reported problem pharmacies to both the College of Pharmacists of B.C. and the Ministry of Health. None of those complaints resulted in the pharmacists, or pharmacies, facing penalties.

The college did not respond on Wednesday to specific questions from The Globe and declined an interview request with registrar and CEO Suzanne Solven. A statement provided by spokesperson Lesley Chang said the college “has a long-standing concern about the negative effects of incentive programs in the practise of pharmacy.” The Health Ministry did not respond to queries from The Globe.

Pharmacies charge a dispensing fee for each prescription, and these fees make up a significant portion of their overall revenue. For patients on income assistance and with First Nations health benefits, a pharmacy that is enrolled with PharmaCare can bill the publicly funded program for up to $10, for each of up to three medications, per patient, per day.

For methadone, the most commonly prescribed medication for opioid use disorder, the program also pays pharmacies an “interaction fee” of $7.70, on top of the dispensing fee, for the pharmacist to witness the patient ingesting it. This means that a single methadone patient could bring in up to $13,760 a year in pharmacy fees for multiple medications. A pharmacy with a few hundred such patients can easily bill PharmaCare for millions of dollars a year.

In an apparent effort to maximize these fees, some pharmacies pay patients cash incentives to fill their prescriptions at their locations, with amounts being kicked back to patients commonly being reported as $50 a week, according to five people receiving such payments. Additional cash is offered to those who recruit others to those pharmacies.

In one case, a pharmacist reported the kickback scheme occurring at his own location to the college. He told The Globe that college representatives acknowledged that it was a problem they had been dealing with for years, and seemed keen on working with him to take action.

However, after collecting evidence for the college and nearly a year of e-mail correspondence and conference calls, the man said the college relayed that no action would be taken, citing staffing shortages and more pressing investigations.

He described the process to The Globe as confusing, convoluted and fruitless. Another pharmacist who reported the issue to the Ministry of Health was told government was aware of the abuse, but no disciplinary action followed.

Lisa Howard, a family physician who provides primary and addictions care in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, said she and her colleagues have reported problem pharmacies to the college on several occasions.

“The College of Pharmacists doesn’t care,” she said. “They said, ‘We can’t accept your complaint unless it comes from the patient who’s directly benefiting from it.’ So the patient has to complain that they’re getting paid, essentially, which doesn’t make sense to me.”

Prescription medications play an integral role in B.C.’s response to the drug crisis. More than 24,000 people in the province receive conventional medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine while, as of December, roughly 4,200 received prescribed alternatives to illicit opioids, an intervention commonly called “safer supply.”

The province has long grappled with the issue of problem pharmacies, having investigated many over the years for offering inducements as well as other improprieties including billing issues and problematic record-keeping. A 2015 crackdown focused on methadone claims led to dozens of Lower Mainland pharmacies either shuttering or being forced to withdraw as PharmaCare providers, meaning they could no longer bill the province for various services.

Duncan Higgon, the interim housing director at PHS Community Services Society in Vancouver, has dealt with pharmacists aggressively pursuing patients within the non-profit’s supportive housing buildings. He said behaviour that was once a “pernicious undercurrent” is not only back, but more brazen than ever before.

“What we’re observing is a predatory shift toward bottom line over patient care,” he said. “And it’s not just that the patients themselves are suffering from a lack of patient-driven care, it’s that there is a huge public cost associated with it.”

The scheme extends beyond offering cash payments to patients for prescriptions they normally would have received. Some patients have reported that pharmacists will counsel them on which medications to ask for, to maximize the number dispensed daily and the resulting billable fees. Several patients told The Globe that their pharmacies would only pay the maximum $50 weekly kickback if they were dispensed at least three medications daily.

Dr. Howard has heard such reports from patients as well. Some pharmacy staff, she cited as an example, will tell patients to request medications for pain or insomnia – self-reported issues that don’t require corroborative objective evidence.

Dr. Howard said patients who have disclosed the scheme to her have felt conflicted about it.

“I find it really challenging, because if you don’t really need this stomach medication, it changes how I provide care for other medical issues,” she said. “It speaks to the fact that people living on the margins of society don’t actually have enough money to live. I would rather be able to prescribe them money.”

Before the pandemic, prescribers had to authorize pharmacy delivery of these controlled substances, which also include methadone, buprenorphine-naloxone and slow-release oral morphine. In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Health Canada issued exemptions under the federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to permit pharmacists themselves to authorize the deliveries and for pharmacy employees, such as assistants, to deliver them on the pharmacist’s behalf.

Health care providers say this expanded delivery service, which was intended to be a temporary measure and used only in exceptional circumstances, has been invaluable to many patients, such as those with mobility issues. But some pharmacies have also exploited it to bolster delivery and witness fees while failing to meet professional standards.

The delivery man at the Vancouver SRO, for example, was supposed to remove the patient’s old fentanyl patches and apply the new ones, as per the patient’s prescription. The patient later told The Globe that while the opioid medications do work for him, the current arrangement allows him to sell some if he needs the money. He tosses the pain and antipsychotic medications, which he only asks for because of the pharmacy kickbacks, he said.

Mat Savage, 50, had been taking methadone to treat his opioid use disorder before recently switching to fentanyl patches. Prior to switching, a Mount Pleasant pharmacy paid him between $15 and $20 a week for his methadone prescription and $5 a week per pill prescription, he said.

“Usually, you give them your scripts and then they meet you around back to give you the money,” he said, adding that the cash would either be in an envelope or rolled up with a rubber band. “Sometimes, they’ll give you the money over the counter, [concealed] in something.”

He recalled travelling to Ontario a few years ago, returning to Vancouver, and learning from a pharmacist that PharmaNet – the province’s database of every prescription dispensed in community pharmacies – showed his methadone was dispensed to him at his previous pharmacy every day, despite his absence.

“I said, ‘I missed all my days,’ and they said, ‘You didn’t miss any days,’ ” Mr. Savage said. “I hadn’t gone there for three weeks, and all those days had been written down that I’d gone there.”

Evan Mellish, 26, says he was prescribed a methadone formulation, an antipsychotic medication and hydromorphone in the spring of 2023, and he brought his prescription to a Downtown Eastside pharmacy that paid him $50 a week. In return, the pharmacy was supposed to either deliver the medications to Mr. Mellish’s residence, or dispense them daily at the pharmacy – neither of which he says happened consistently.

Mr. Mellish said he would be able to obtain his medications if he showed up to the pharmacy early in the morning, but that if he arrived near closing time they would sometimes tell him he had already taken it.

“It would make me feel like I’m crazy, and I would second-guess myself,” he said.

Mr. Mellish said he began keeping track after the first several times it happened, and estimates that the pharmacy failed to dispense his medications to him between five and 10 times over several months. He gave up on trying to adhere to his prescribed medications and went back to using illicit drugs.

“I pretty much just quit altogether, like I didn’t even bother going to see the doctor I was going to,” he said. “I’m just using [fentanyl] regularly now, but cutting down a lot.”

When patients fail to receive their prescriptions, pharmacists are required to reverse their claims in PharmaNet – a process that automatically triggers a billing correction. Instead of making this change, some pharmacies leave powerful medications on doorsteps, or with neighbours, in congregate housing, a practice that violates protocols and risks theft, diversion and the health care and privacy of the patient. In other instances, they’re never dispensed at all.

Dr. Howard has had patients report not having received their medications despite them having been marked as dispensed in PharmaNet. Resulting issues include improper documentation and patient safety issues, particularly around dosing, she said. Some medications are marked as filled despite patients being out of town, or dead – reversed only when she phones the pharmacy to inform them.

Mr. Higgon said patients who try to report to a hospital or clinic that they have not received their medication, despite it having been marked as dispensed, are often disbelieved and labelled as having drug-seeking behaviour. Those who relapse as a result risk overdose and death.

“At the end of the day, that’s what we’re talking about here,” he said. “There are a whole collection of concerns here. People will die.”