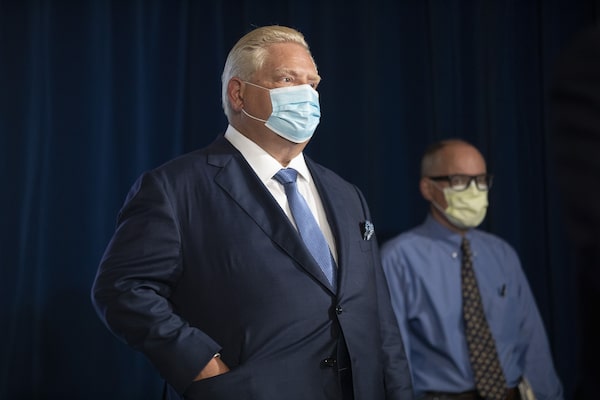

Ontario Premier Doug Ford (left) stands alongside Dr. Kieran Moore, the Chief Medical Officer of Health of Ontario, during a press briefing at the Queens Park Legislature in Toronto, on Oct. 15.Chris Young/The Canadian Press

The Ontario government is not equipping Long-Term Care Ministry inspectors with powers to prosecute nursing homes under proposed legislation, making it highly unlikely that any operator of a facility will face hefty fines, critics say.

A new long-term care act unveiled by the government last week would double fines for those who operate homes. But the new act stops short of appointing ministry inspectors as provincial offences officers, which would give them the authority to prosecute cases and lay charges in court.

Without that authority, the only recourse for inspectors is to go through the cumbersome process of asking police to prosecute the most egregious offences, including a home’s failure to report abuse, the critics say.

Under the existing legislation governing long-term care – the tightly regulated and publicly subsidized spaces most people know as nursing homes – no home or individual has ever been convicted under the quasi-criminal Provincial Offences Act. When inspectors find violations of Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes Act, punishments have been limited to compliance orders asking the facilities to shape up.

The government announced last week that it is strengthening enforcement of the sector by doubling fines to up to $200,000 plus 12 months in prison for an individual convicted of a first offence under the Provincial Offences Act. The fine for a home would jump to $500,000 from $200,000.

To prevent another pandemic catastrophe, long-term care needs a long-term fix

Jane Meadus, a lawyer at the Advocacy Centre for the Elderly in Toronto, said the stiffer fines are “toothless,” because the government has never used legislation already on the books to successfully prosecute any home or individual.

“If they’re not actually laying charges, does it matter what the fine is?” Ms. Meadus said in an interview.

Despite numerous examples of abuse and neglect exposed in many nursing homes during the coronavirus pandemic, no one lost their operating licence or faced other penalties. COVID-19 tore through the sector, killing 3,824 residents. Many of them died alone in virus-stricken, understaffed homes.

“If nothing that we’ve seen so far in countless cases of elder abuse have been reasons to lay any fines, I don’t know what will,” Samir Sinha, director of geriatrics at the University Health Network and Sinai Health System in Toronto, said in an interview. “So why bother doubling something that you’re probably not even willing to use?”

The higher fines are part of Premier Doug Ford’s pledge to overhaul the province’s rules governing long-term care. His government is promising to spend billions of dollars on hiring more workers for the chronically understaffed sector, to double the number of inspectors and to build new facilities to replace the aging stock of homes with multibed wards.

For the first time, the proposed legislation would allow ministry inspectors to levy administrative fines of up to $250,000 against homes. Such penalties – which are separate from those under the Provincial Offences Act – would be a “big step,” Ms. Meadus said, because they would give inspectors more clout to enforce compliance orders issued to a home.

But Ms. Meadus said the proposed long-term care legislation fails to put inspectors on par with their counterparts in the labour and environment ministries, who are appointed as provincial offences officers with the authority to prosecute cases.

Just last week, the Ministry of Labour charged a nursing home with workplace safety violations, after a COVID-19 outbreak left eight residents and one staff member dead. The charges, laid under the Occupational Health and Safety Act against Kensington Village in London, Ont., mark the first time the Labour Ministry has taken enforcement action against any home since the onset of the pandemic.

According to a copy of the charges filed in Ontario Court of Justice, the home is accused of “knowingly furnishing an inspector with false information,” in connection with cleaning records, and of failing to provide adequate information on proper hand hygiene and the donning and doffing of personal protective equipment.

Tracie Klisht, executive director of the for-profit home, said in a statement that its owner, Sharon Village Care Homes, “has always strived to provide, and maintain, a safe workplace for all our employees.”

Amber Irwin, a spokeswoman for Long-Term Care Minister Rod Phillips, said in an e-mail on Sunday that the ministry plans to hire some inspectors with an investigative background who “have the skills and certification needed to investigate and lay provincial offence charges when warranted.”

Dr. Sinha questioned the government’s resolve to strengthen its enforcement measures, noting that it all but dismantled wide-ranging annual inspections of homes and also introduced legislation that makes it more difficult, if not impossible, for families who lost loved ones to sue facilities and hold accountable those who run them.

“This new act makes it sound like they are doing a heck of a lot when they actually aren’t,” he said.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.