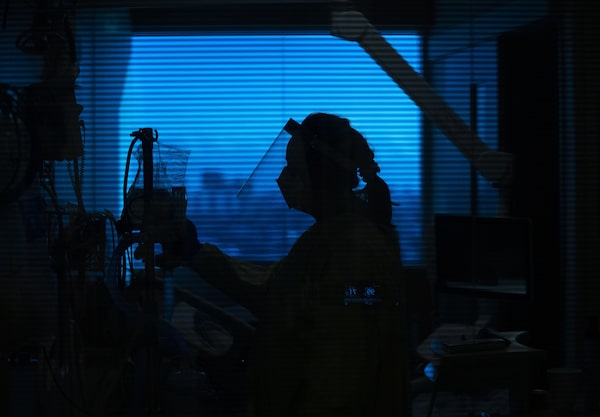

Unions and opposition politicians have charged that Bill 124 drove workers out of the health care sector and is a leading cause of the staffing shortages currently hampering hospitals.Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press

The Ontario government is expected to save $9.7-billion through its contentious wage-cap legislation that temporarily limits pay increases for public-sector workers, the province’s fiscal watchdog projects.

A report on public-sector compensation released by the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) Wednesday highlights the monetary impact Bill 124, which caps wage increases to 1 per cent annually for a three-year period, has had on the government’s finances and wages of the public service.

It also warns that inflation, a court challenge surrounding the law and an increase in job vacancies could compel the province to spend more on wages over the next few years.

Financial Accountability Officer Peter Weltman said the projected savings from Bill 124 could be significantly reduced if the ongoing court hearing brought forward by unions against the legislation is successful.

His office estimates that the province would owe $8.4-billion to make up for lost increases, including $2.1-billion retroactively in this fiscal year. (This is less than the estimated savings from the law because the FAO doesn’t expect non-unionized workers will be compensated for the reduced wages).

Bill 124, which was introduced by Premier Doug Ford’s government in 2019 as a cost-saving measure, has been a focal point throughout the pandemic. Unions and opposition politicians have charged that it drove workers out of the health care sector and is a leading cause of the staffing shortages currently hampering hospitals.

The legislation has already limited wage increases for most provincial employees, but 30 per cent will soon negotiate a new collective agreement that will be subject to the cap, including more than 100,000 hospital workers, the FAO report said. The Canadian Union of Public Employees has about 50,000 hospital staff, including nurses, who will be subject to the wage restraint when they enter into a new deal.

Michael Hurley, president of CUPE’s Ontario Council of Hospital Unions, said the wage cap predominantly hinders women who have been working on the front lines of the pandemic and called for the government to scrap the bill to avoid further worker turnover.

“No wonder we have a staffing crisis in hospitals when the very work force who have borne the brunt of pandemic risks are told they deserve wages that significantly lag behind inflation,” he said in a statement.

Job vacancies in the province’s health sector have nearly doubled since 2019, the FAO report found, with 16,020 hospital position vacancies in the second quarter of 2022.

As hospitals grapple with staffing challenges and crammed emergency rooms, interim NDP Leader Peter Tabuns said he’s concerned that the situation will only get worse, warning that health care workers will look elsewhere if their salaries are capped after working through the pandemic for more than two years.

Mr. Tabuns also took issue with the government’s decision to limit wage increases to save money rather than spend more in the health care system and increase wages for those workers. The province just recorded a $2.1-billion surplus in 2021 to 2022 after initially forecasting a $33.1-billion deficit in the 2021 budget.

Some emergency rooms were forced to temporarily close their doors throughout the summer and waiting times to be admitted to hospital reached a record-high 20.7 hours in July.

“If you’ve gone to an emergency room that’s been closed, if you’re one of the parents whose children is not getting pediatric surgery because of the backlog because hospitals are understaffed, you’re not going to see this as a good thing,” he said. “They cannot balance their budget on the backs of the people who have risked their lives in our hospitals and clinics these past few years.”

Provincial public-service salary increases were an average of 1 per cent in both 2020 and 2021 as a result of the legislation, according to the FAO data. That puts the province behind its federal and municipal government counterparts where workers received an average annual wage increase of 2 per cent and 1.6 per cent, respectively.

The province lagged behind the other jurisdictions even before Bill 124 came into effect, with an average annual increase of 1.2 per cent from 2011 to 2019.

Responding to the FAO report, provincial Treasury Board spokesman Ian Allen pointed to an increase in hospital employment by 4.9 per cent in 2021, a significant growth from an average growth of 1.2 per cent from 2011 to 2019.

“The FAO report confirms that we are protecting the long-term sustainability of Ontario’s front-line public services for years to come, which is allowing our government to make critical investments to build Ontario by strengthening critical frontline services like health care, education and infrastructure,” Mr. Allen said in a statement.

The FAO’s Mr. Weltman said that the province will need to hire an additional 138,669 employees in the private sector as well as long-term care, home care and child-care sectors in order to deliver its planned programs, including more than 28,000 staff in hospitals.

With wage growth well below inflation, he said the province may need to further increase wages to attract workers. A wage-increase projection taking inflation into account could see an additional $6.8-billion spent by the province over the next five years.

“If you aren’t filling the positions, then you aren’t offering the level of service that you’ve tried or promised to offer,” he said.

In total, the government spent $48.2-billion on wages in 2021 to 2022, which the FAO expects to climb to $56.9-billion by 2026 to 2027.