Early last September, nurse Jennifer MacNab was approaching a breaking point in her fight against tuberculosis in the Nunavut hamlet of Pangnirtung.

For weeks, she had been calling and e-mailing her superiors, begging for help in controlling the spread of an infectious disease that can be fatal if left untreated. TB cases were mounting and “critical tasks” were piling up, Ms. MacNab warned.

As the only public health nurse working in the fly-in community last summer, she found there weren’t enough hours in the day to trace all the contacts of patients with contagious TB. She estimated there were, “at minimum,” 100 contacts of newly diagnosed patients who needed assessments. She didn’t have time to start everyone who needed it on preventative treatment or to chase down all those sick with active cases of TB to give them their daily pills.

“The TB program needed manpower a month ago,” Ms. MacNab wrote in an e-mail to territorial health officials on Sept. 9. “The program is failing every single day. TB continues to spread. It needs help immediately. I have been utterly clear in my repeated requests. I am at a loss where to go to have my words heard.”

Six weeks earlier, on July 29, Yves Panneton, the nurse in charge of Pangnirtung’s health centre, wrote to some of the same officials to say the community was in the midst of a tuberculosis outbreak. But Government of Nunavut health officials disagreed and held off on publicly declaring an outbreak until late November.

They also refused, until May of this year, to divulge the number of TB cases in Pangnirtung, despite the territory’s top Inuit organization and its information and privacy commissioner pressing the government to report TB cases in all 25 Nunavut communities, just as it had for COVID-19.

Ms. MacNab’s and Mr. Panneton’s e-mails are among more than 200 pages of correspondence and internal documents about the TB outbreak in Pangnirtung obtained by The Globe and Mail through an access-to-information request. The paper trail, along with interviews The Globe conducted with Pangnirtung residents, TB experts, health-care workers and government officials, reveal how the territorial government failed to curb the spread of TB last summer, when declaring an outbreak sooner and deploying more front-line staff to the Baffin Island community might have prevented tuberculosis from infecting as many people as it did.

Some Pangnirtung residents say the Government of Nunavut isn't doing enough to combat tuberculosis, a disease that has long plagued Inuit communities.

The Globe and Mail

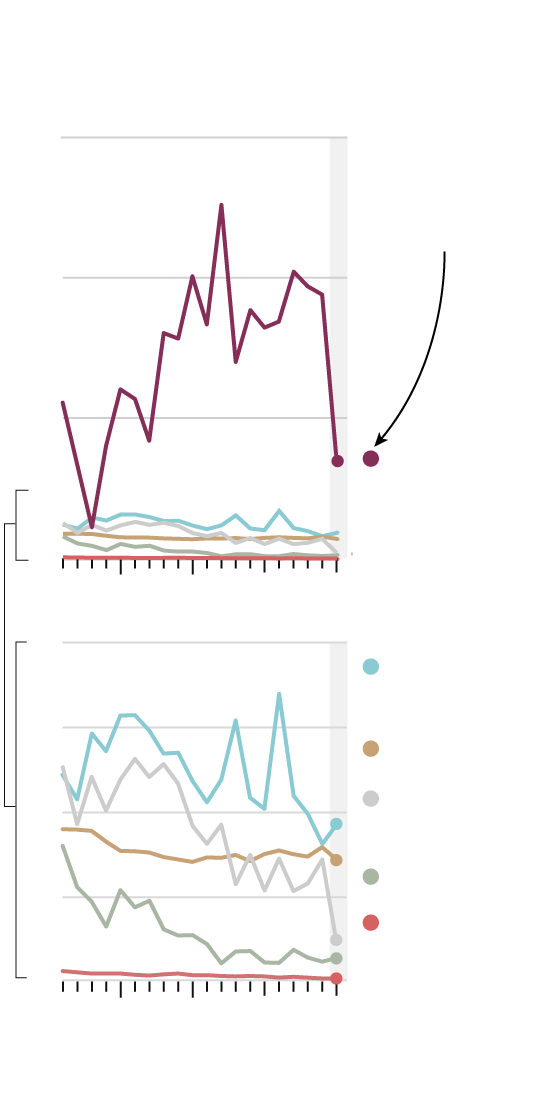

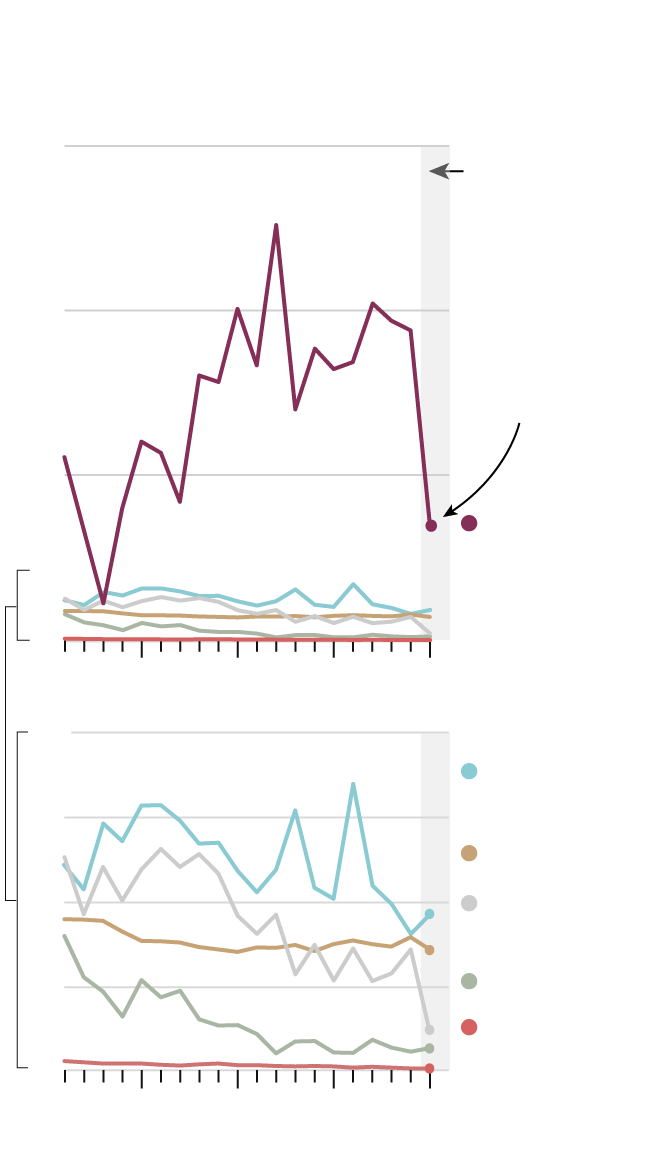

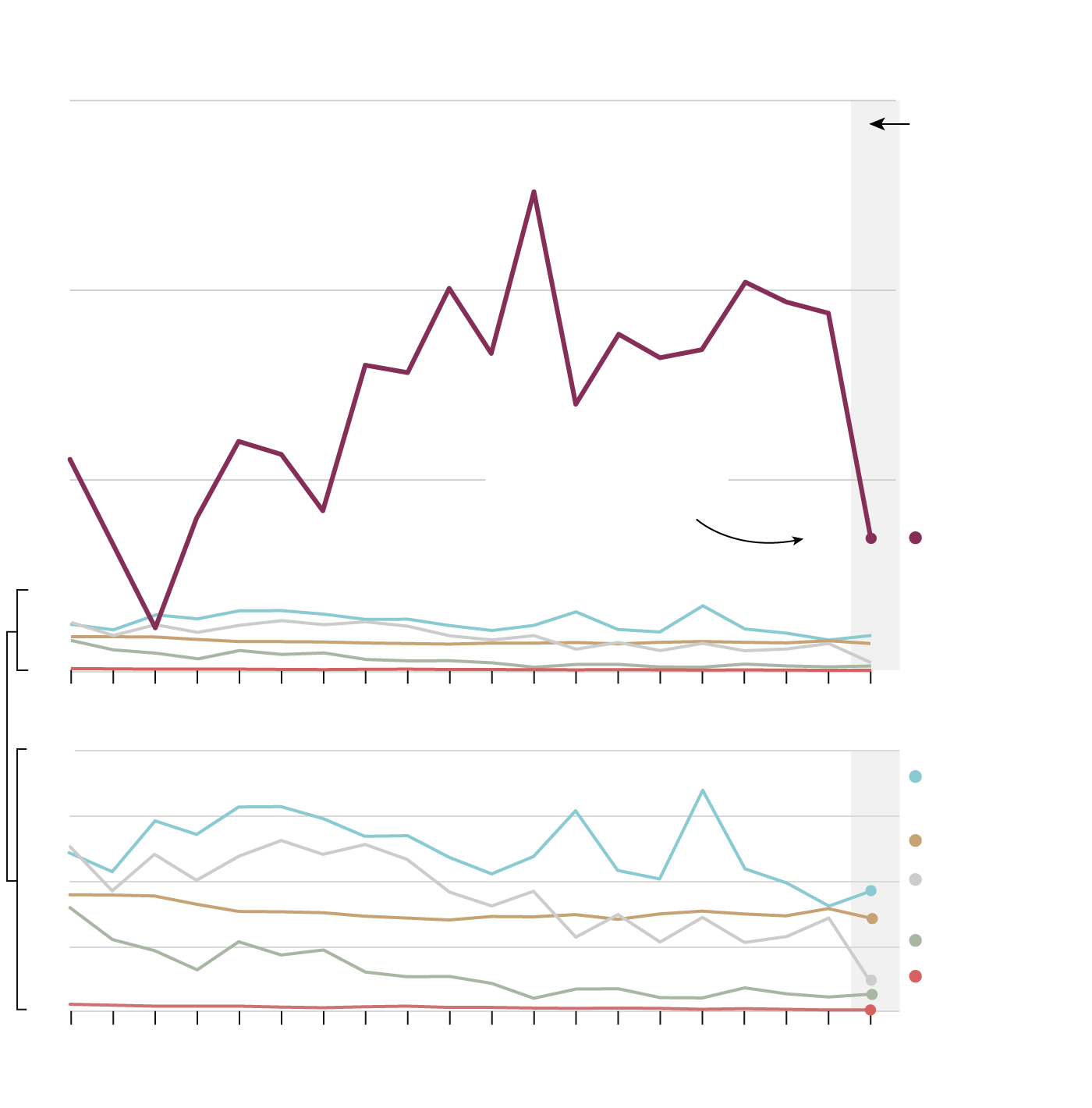

Thirty-one active cases and 108 latent cases of tuberculosis were identified in Pangnirtung between January 2021 and May 2022, making the outbreak the largest to be publicly disclosed in Nunavut since 2017, when 15-year-old Ileen Kooneeliusie died of TB during an outbreak in Qikiqtarjuaq.

Given its population of only about 1,500 people, Pangnirtung’s TB incidence rate in 2021 ranks among the highest in the world, exceeding rates regularly seen in the least developed countries in Africa.

Most Canadians think of tuberculosis as a scourge of the past, if they think about it all. Inuit don’t have that luxury. In one recent year, Inuit tuberculosis rates were nearly 300 times higher than the rates among non-Indigenous people born in Canada.

That disparity prompted Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government to make a bold promise in 2018: it vowed to eliminate tuberculosis in Inuit communities by 2030.

The Liberals’ pledge was audacious because most experts agree that eliminating tuberculosis requires resolving the social and health disparities that make residents of isolated northern communities like Pangnirtung vulnerable to the disease in the first place. TB thrives in substandard, overcrowded housing, and is much likelier to make infected people severely ill if they are undernourished, smoke cigarettes, have chronic diseases and lack consistent access to medical care.

Although the federal government made the elimination pledge, Nunavut, like all provinces and territories, is responsible for providing health care, and that includes responding to infectious disease outbreaks. In 2018, the federal government allocated $13-million in funding for TB countermeasures to Nunavut, but much of that money went unspent as TB spread in Pangnirtung because the territorial government has yet to agree on a regional TB action plan with Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the territory’s lead Inuit organization and the recipient of the federal funds.

Tuberculosis, “is a preventable, treatable infectious disease,” said Jane Philpott, the former health and Indigenous services minister who made the commitment on behalf of the federal government alongside leaders of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, a national organization representing 65,000 Inuit.

“Affluent, non-Indigenous people in Toronto don’t die of tuberculosis, but young people from Inuit regions have died of tuberculosis in this decade. It’s a blatant demonstration of the disparities that we continue to allow and perpetuate and turn a blind eye to.”

In many ways, the handling of the tuberculosis outbreak in Pangnirtung lays bare all that plagues the delivery of health services in Nunavut, a subject The Globe has been investigating as part of an ongoing series this year. The Nunavut Department of Health and its local health centres – the only sources of medical care in fly-in hamlets outside the capital of Iqaluit – are chronically short-staffed.

While TB was spreading in Pangnirtung last summer, health centres in other Nunavut communities were closing their doors to all but emergency care provided by paramedics because few nurses could be enticed to work in the territory during a national nursing shortage.

Most of the well-meaning but overworked southern nurses who serve Nunavut’s hamlets do so temporarily, making it difficult for them to build trust with communities whose high health needs are complicated by mental illness, addiction and intergenerational trauma caused by residential schools in some cases and forced resettlements in others.

With too few health-care workers and too little trust, effective tuberculosis control programs are difficult to deliver. Such programs require not just consistent staffing, but money and political will, all of which have been in short supply for tuberculosis during the pandemic.

Still, the Government of Nunavut could have handled the situation differently. Its public health leaders could have declared an outbreak and disclosed case numbers earlier, according to several tuberculosis experts The Globe interviewed, empowering Pangnirtung residents to take precautions. They could have ordered community-wide screening for TB, as they did during the Qikiqtarjuaq outbreak. They could have asked other levels of government for backup sooner, something Mr. Panneton told The Globe might have mitigated the outbreak.

“The help that I asked for,” he said in an interview, “was always given to me when it was too late.”

The community of Pangnirtung is one of the natural beauties of the far north. Located just below the Arctic Circle at the head of a dramatic fjord on Cumberland Sound, it is surrounded by craggy, snow-capped mountains and glaciers.

In the shadow of this grandeur sits the hamlet itself, a collection of mostly single-storey homes and multiplexes built on pilings above the permafrost. A Department of Health regional office is headquartered in Pangnirtung, a callback to the period between 1930 and 1972 when the community hosted the only hospital in the eastern Arctic, St. Luke’s Mission.

In the spring, ice-fishing at cabins on the land is popular. On one blue-sky day in mid-May, second and third graders from Alookie School piled into wooden sleds pulled by Ski-Doos for the two-hour ride to a camp Pangnirtung’s schools have been running for decades. Children, teachers and elders bobbed for fish using wooden sticks and string, shedding their coats because the bright sun on the snow made it fell balmier than the real temperature of -5 C.

While the schoolchildren were fishing and hunting geese, Nancy Anilniliak was doing administrative work in the hamlet office, a low-slung blue building on the community’s coast. She sported a disposable mask covered in blue and gold snowflakes. “I’m wearing my mask for two reasons,” she explained. “COVID is still here. But my main concern at this time would be TB.”

For Ms. Anilniliak, it was hard to figure out just how concerned to be. As of that day in May, the Government of Nunavut hadn’t released any official statistics yet about the tuberculosis outbreak.

“It would be helpful to know what the number is,” Ms. Anilniliak said. “Is it declining? Is it increasing? We don’t know any of that.”

The situation was particularly baffling to Ms. Anilniliak because of what was happening – or rather, not happening – in the hamlet’s community hall, one of its few public spaces.

The Nunavut Department of Health rented the hall for $10,000 a month beginning March 1 to operate a satellite TB clinic, a signal of the outbreak’s severity. Two-and-half months later, the hall sat empty, its pool tables covered in black cloth, its foosball tables pushed to the side of the room. A spokeswoman for the Nunavut Department of Health blamed the delay on a shortage of skilled technicians to install the appropriate wiring and internet network connections for workstations in the hall.

The satellite clinic, which finally opened in June, will serve as an overflow workspace because Pangnirtung’s health centre is too cramped to accommodate extra public health staff needed to screen and treat people for TB. TB outbreaks often last years. Managing one is a major undertaking.

Tuberculosis is caused by airborne bacteria that usually lodge in the lungs, where they can cause fever, drenching sweats, weight loss, muscle aches, deep fatigue and a nagging, sometimes bloody cough. When the germs first find their way into the human body, they usually cause a latent or “sleeping” infection that doesn’t make people sick and isn’t contagious but can later turn into potentially fatal active TB disease.

Today, latent TB infection can be cured with antibiotics taken once a week for three months. Active TB can also be cured, using antibiotics taken daily for six months.

Depending on the circumstances, latent TB infection can be identified using a blood test or a tuberculin skin test, a procedure that involves injecting a tiny amount of liquid under the skin of the forearm to see if, two or three days later, a hard, raised area of swelling appears around the injection site. Diagnosing active TB disease can require a physical exam, chest X-ray and a sample of mucus coughed up from the respiratory tract.

With every confirmed case, the workload swells. More contacts to trace, more people to screen, more patients to treat.

Ms. Anilniliak, whose office is located just down the hall from the community space now used for the TB clinic, understands the history of tuberculosis as well as anyone in Pangnirtung. As a child, she was diagnosed with TB and taken away on the C.D. Howe, an Arctic patrol vessel and medical ship. Her voyage ended at the Hamilton Mountain sanatorium, a facility that cared for more than 1,200 Inuit with tuberculosis between 1958 and 1962.

In 2019, Justin Trudeau apologized for how the federal government managed TB in the Arctic in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, calling it a “colonial” and “misguided” policy that ripped patients away from their communities, sometimes without their consent.

That history was a factor in how physicians and government officials responded in the early days of Pangnirtung’s outbreak last summer, when the vast majority of new cases were linked to one contagious patient who was couch surfing and refusing to isolate, according to Mr. Panneton, who ran Pangnirtung’s health centre from March to September of 2021.

From top left: Inuit board the C.D. Howe, a medical ship that transported tuberculosis patients to the south; Colatah, 2, is examined aboard the C.D. Howe in 1951; Dr. James Osborne sees a patient before heading to Pangnirtung to assume medical duties at the hospital; and the Mountain Sanatorium, a Hamilton facility where more than 1,200 Inuit received tuberculosis care between 1958 and 1962. Library and Archives Canada; Black Mountain Collection / Hamilton Public Library

At the time, Mr. Panneton said, he and his colleagues needed two things: more public-health workers and a way to convince the contagious patient to isolate or leave the community. “The two are really key and critical,” he told The Globe, “because even if I had more resources, I had a super spreader in town. It’s like you’re trying to put a fire out and someone’s throwing gas on it.”

Mr. Panneton, who now works overseas for an NGO, said Michael Patterson, Nunavut’s chief public health officer, and other senior health officials were reluctant to force the patient to leave the community and isolate at the hospital in Iqaluit, something Mr. Panneton felt made the outbreak worse.

Public health leaders working in Inuit communities have spent decades emphasizing that TB can now be treated with a long course of antibiotics at home. Removing a patient, even for the safety of the community, could undermine those efforts, leading other Inuit to refuse TB testing out of a fear of being sent away.

The contagious patient eventually left Pangnirtung voluntarily on a medevac bound for the hospital in Iqaluit, according to e-mails exchanged among health officials, nurses and doctors.

Jamie Evic, Pangnirtung’s senior administrative officer, said finding places for TB patients to isolate in the community is a huge obstacle to controlling spread of the disease. Sprawling extended families often live together. There were 120 individuals and families in the hamlet on the waiting list for a home as of the end of March, according to the Nunavut Housing Corp. A new public housing unit hasn’t been built in Pangnirtung in more than a decade.

The Nunavut Department of Health was able to find more southern nurses and local TB assistants willing to work at the Pangnirtung health centre in the fall, but the vast majority of the nurses were temporary. In most cases, the Department of Health isn’t permitted to advertise for permanent jobs until a different government department confirms a staff housing unit is available, which can take years.

“We have hemorrhaged full-time staff over the last year, and have been unable to post any positions due to no housing approvals,” Chris Nolan, the executive director of health for the Qikiqtaaluk region of Nunavut, wrote in an Oct. 25 e-mail to Dr. Patterson and another senior health official. “Our casual and agency [Public Health Nurses] are not wanting to return due to the high workload (working 12-14 hrs/day 7 days/week) so we are going to be in a situation where we have new staff every few weeks, if we can locate staff at all.”

In an interview in October, Mr. Nolan, a Pangnirtung resident, described his hunt for places for extra nurses to stay. He had blocked off rooms at Pangnirtung’s one hotel and its only bed-and-breakfast. When The Globe interviewed him again in April, Mr. Nolan had temporarily moved in with his partner in Iqaluit so transient health staff could use his apartment.

As they scrambled to find and house staff last fall, health officials in Iqaluit and Pangnirtung also discussed publicly declaring an outbreak. Dr. Patterson resisted making the call for months, writing that Pangnirtung’s situation constituted a “cluster,” not an outbreak, because all the known cases were linked. Until there was a stand-alone case whose origins couldn’t be traced, he wouldn’t deem it an outbreak.

Nunavut’s tuberculosis manual, however, actually cites the importance of links between cases in its definition of an outbreak, as, “when there are more TB cases than expected within a geographic area or population during a particular time period, and there is evidence of recent transmission of TB bacteria among those cases.”

Krystie Hall, the assistant director of health programs for the Baffin Region, worried that failing to declare an outbreak hampered the response. “My concern is that classifying this as a cluster rather than an outbreak means that it may get overlooked in the provision of resources,” Ms. Hall wrote to Dr. Patterson and others on Oct. 21.

Dr. Patterson replied that a public pronouncement wouldn’t be warranted until “much of the community, if not the entire community is at risk of TB,” although he conceded the time had come to ask other governments for backup staff.

In early November, Dr. Patterson requested additional public health nurses through a process known as OFMAR, the Operational Framework for Mutual Aid Requests. The Public Health Agency of Canada manages the process, but the nurses are generally supplied by other provinces and territories. Three public health nurses were deployed to Pangnirtung through OFMAR between December 2021 and March of 2022, each of them for a stint of between three and six weeks, according to a spokeswoman for federal Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu.

A few weeks after Dr. Patterson made the OFMAR request, a Nunavut public health physician advised Dr. Patterson and others that some Pangnirtung teenagers with no known link to other cases tested positive on TB skin tests. The outbreak notice and public health advisory were issued a week later.

The Nunavut Department of Health declined to make Dr. Patterson available for an interview after The Globe visited Pangnirtung to report this story in May, but a spokesman said that, prior to the outbreak declaration, there was no increased risk of TB exposure for the majority of people in Pangnirtung. Nunavut Health Minister John Main, who also declined to comment, told the Nunavut legislature on June 7 he was confident the Department of Health made the “right choice” in declaring an outbreak when it did.

The Nunavut government also declined to reveal TB case counts for each community, despite a non-binding ruling by the territory’s privacy commissioner that numbers be released to The Globe. Every reference to the number of TB cases in Pangnirtung was redacted in the access-to-information documents released to The Globe this spring.

In May, however, after receiving a list of e-mailed questions for this story and a request for public transparency from Pangnirtung Mayor Eric Lawlor, the Nunavut Department of Health issued a news release disclosing the diagnosis of 139 cases in the community in 18 months, 31 of them active. The department promised to provide an update every three months and said the outbreak’s curve was flattening, a hopeful sign.

Still, Deputy Mayor Markus Wilcke said letting TB bacteria spread to 139 people in Pangnirtung amounts to “negligence.” A long-time northern nurse who moved to Pangnirtung to work at the health centre in 2000, he remembers how comparatively well-controlled tuberculosis was in the Canadian Arctic in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s. In that era, experienced, permanent nurses were trained to “Think TB” at all times and to screen residents annually for TB, nipping potential outbreaks in the bud.

If TB is spreading in other Nunavut communities, the public still has no way of knowing. Mr. Main and the health department continue to argue that releasing case tallies in tiny hamlets would risk identifying patients and stigmatizing entire Inuit communities.

For his part, Dr. Patterson told The Globe during an October interview in Iqaluit that he had some regrets about releasing TB data during the 2017-2018 outbreak in Qikiqtarjuaq.

Publicizing the toll, “created a lot of difficulty for residents of Qikiqtarjuaq,” Dr. Patterson said. “They felt almost shunned when they were in other communities. We have to find that balance with tuberculosis, and not create that kind of stigma.”

But Inuit leaders want the information made public. In fact, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the territory’s lead land claims organization, says the government’s refusal to share TB case counts by community – as it did with COVID-19 – is the main stumbling block to the two sides signing a regional TB action plan that should have been in place before the pandemic.

Nunavut is the only Inuit region that has failed to do so. The Nunavut department of health declined to explain the holdup, except to say through a spokeswoman that talks with Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. continue and an agreement is close.

But Jesse Mike, the director of NTI’s social and cultural development department, said the sticking point is information sharing. Her organization can’t assess progress toward TB elimination or send aid to the right communities if the government won’t say where tuberculosis is spreading.

“It’s frustrating,” Ms. Mike said, “because who’s losing at the end of the day? Who’s losing out on extra help and support? The people that need it.”

The impasse means that only $2-million of $13-million in federal TB funding earmarked for Nunavut has found its way to the territorial government, the Nunavut health department said. (Ms. Mike said the number is closer to $1.5-million.) The rest of the money remains with NTI, which has spent some on its own TB initiatives, including paying the salary of a TB program manager and distributing food-and-supply hampers to Pangnirtung residents.

Despite COVID-19 siphoning attention and resources away from TB for two years, Ms. Hadju and ITK president Natan Obed say they remain committed to elimination of the disease by 2030. The outbreak in Pangnirtung is “devastating,” Ms. Hajdu said. “It’s a call to action for all of us.”

One of the Pangnirtung residents who has questions about how the territorial government handled the outbreak is Robert Joamie.

A 44-year-old full-time garbage worker for the hamlet, he fell ill with an active case of tuberculosis in October 2021, about a month after nurse Jennifer MacNab ended her contract as a casual nurse early and left the community. (She declined an interview request.)

Mr. Joamie’s girlfriend and three of their children also developed active cases of TB. The family had to isolate in their two-bedroom home for two months.

Around Christmas, Mr. Joamie felt dangerously short of breath and had to be flown on a medevac to a hospital in Iqaluit where a tube was placed in his chest to drain fluid from his lungs. “It was really, really hard to breathe,” Mr. Joamie recalled in an interview in May. “I was getting tired easily every day, like I couldn’t stand up.”

Until he was caught up in a real-life outbreak, Mr. Joamie’s experience with tuberculosis had been confined to the movies. As a teenager, he starred in an acclaimed 1993 Hollywood movie called Map of the Human Heart. He played the young version of Avik, an Inuit boy who contracts tuberculosis in the early 1930s and is taken by a white man to a sanatorium in Montreal to be cured.

Canadians of a certain age may recognize Mr. Joamie from another of his childhood acting jobs. In a Heritage Minute, he played the Inuit boy who tells an RCMP officer why his family is building an Inukshuk. “Now the people will know we were here,” he says.

As Mr. Joamie worked outside on the hamlet’s sewage truck, long-time Pangnirtung resident Looee Mike sat at her kitchen table, slicing frozen caribou marrow on to crackers and reflecting on how TB has affected her community.

Ms. Mike, an Anglican minister born on the land in a seasonal camp outside Pangnirtung, recalled how Mr. Joamie called in to the Inuktitut radio program she hosts to beg for food. He couldn’t go to work; his children missed two months of school. His extended family and other members of the community answered his call, dropping meals at this house.

Ms. Mike sees government transparency about TB outbreaks as a way to get past whatever stigma clings to the disease. She also hopes publicizing the case numbers will bring more attention and medical help to Pangnirtung.

As it stands, Ms. Mike likens her community’s plight to being alone on an unstable floe edge, where open water meets the ice attached to the shoreline. The ice can tip over, “and you’re lost,” Ms. Mike said. “That’s how we feel. Because there’s no support, there’s no knowledge given.”

The Globe and Mail’s health reporter Kelly Grant is taking an in-depth look at health care in Nunavut and the challenges its residents face accessing it. Over the course of 2022, she’ll examine why the territory’s residents have some of the worst health outcomes in the country and what changes are needed to deliver better care.

Ms. Grant is working with photographer Pat Kane. Based in Yellowknife, Mr. Kane takes a documentary approach to his stories that focus on Northern Canada. Mr. Kane identifies as mixed Indigenous/settler and is a proud Algonquin Anishinaabe member of Timiskaming First Nation in Quebec.

If you have information to help inform The Globe’s reporting on Nunavut, please e-mail kgrant@globeandmail.com