:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/AMCF6T3IAFEAFOQ7OK7CNIZI54.jpg)

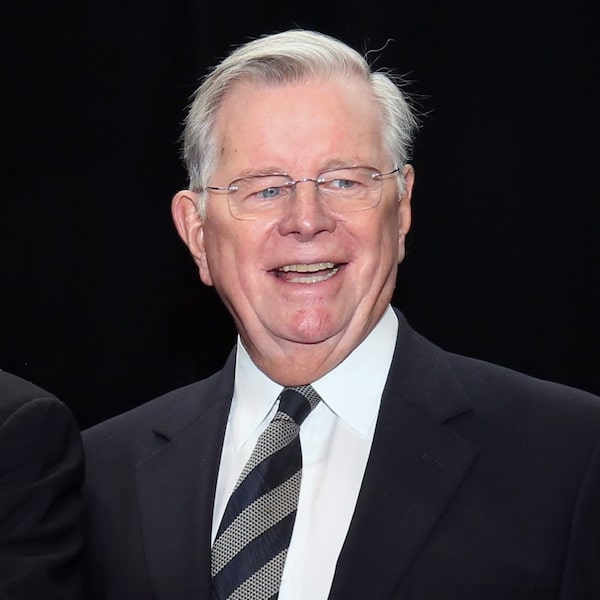

When Michael Harvey got into the access to information business, he didn’t imagine that he’d be recognized at the grocery store.

Most provincial information commissioners carry out their jobs in relative obscurity, issuing reports detailing how their respective governments fail the masses by keeping public records hidden, but which few people read and which rarely lead to change. But as Information and Privacy Commissioner of Newfoundland and Labrador, which has enacted Canada’s most modern and robust system for ensuring such documents are released to the public, Mr. Harvey has assumed an unusually large profile.

His clout stems in part from a political scandal about excessive government secrecy that gave rise to the system he now oversees, and is magnified by the province’s small size (530,000 people). He regularly goes on talk radio, makes headlines or writes opinion pieces weighing in on access and privacy issues.

“We’re very proud of our act,” Mr. Harvey says. “As far as I know, it’s the best access system in the country, and it deserves to be protected and, potentially, emulated.”

Compared with many other Canadian jurisdictions’ access systems, Newfoundland is a promised land. The vast majority of access requests it receives are completed within a month. In the 2020-21 fiscal year, no fees for access requests were charged. And the number of requests has soared since 2015 – a sign, Mr. Harvey says, that getting information has never been easier and that the public is engaging with its government.

The province also sits atop a ranking of federal, provincial and territorial access laws, according to the Centre for Law and Democracy.

Access laws, also known as freedom of information laws, exist in jurisdictions across the country, and require public institutions to disclose information in response to formal requests, with limited exceptions. When these laws were implemented, they were considered an essential underpinning of democracy – ensuring that the public was fully apprised of what and why the government takes certain courses of action.

The Globe and Mail recently launched Secret Canada, an investigation into the country’s broken access systems. The probe revealed that public institutions are routinely breaking these laws by overusing redactions and failing to meet statutory timelines, and that they face few – if any – consequences for ignoring precedents set by courts and appeal bodies.

The story of Newfoundland and Labrador serves as a powerful example that access systems do not have to embrace the entropy and culture of secrecy that seems to pervade virtually every other province, territory and the federal government. In most jurisdictions, access only ever moves inexorably in one direction: toward greater delays, more redactions and less transparency for the public.

Instead, a confluence of events – a scandal, a troubled and infamous infrastructure project and a lame-duck government – allowed the province to break from the same downward spiral traced by Canada’s other access systems.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/UMYIYRF4D5C3RD3SEMWOPWE6ZE.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/CYKXFECHRZAA5LB2ZDRTMFM2ZA.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/HLKCRLUFZFB4JDHZXK67FQ3E6U.JPG)

A decade ago, the government of Newfoundland and Labrador was at a crossroads.

In 2012, the Progressive Conservative government of the day unveiled Bill 29, which significantly restricted the public’s ability to access government records.

The new legislation limited the kinds of documents people could ask for, allowed the government to reject requests as frivolous or vexatious and hiked the hourly cost for processing a request.

Bill 29 was not well received. People protested, opposition members filibustered the bill for 70 hours – a record – and a transparency group said the new law would worsen the province’s global access ranking.

Over the next two years, Bill 29 became an albatross around the government’s neck, synonymous with secrecy, paternalism and mismanagement.

“Bill 29 was such a political fiasco,” Mr. Harvey recalls. “Many of us would point back and say that Bill 29 was the beginning of the end for the administration of the day.”

Kathy Dunderdale announces her resignation as premier in 2014 as her interim replacement, Tom Marshall, looks on at left.The Canadian Press

By 2014, public opinion had turned against the government. The Progressive Conservatives were polling at 33 per cent, compared with the Liberal opposition’s 53 per cent. The province’s premier, Kathy Dunderdale, had resigned, and finance minister Tom Marshall was tapped as an interim replacement. One of his first moves was to announce a full review of the controversial law, to be conducted by an independent civilian committee.

Three people were selected for the job: Clyde Wells, who had served as Newfoundland’s premier from 1989 to 1996; Jennifer Stoddart, a two-time former privacy commissioner, first in Quebec and then federally; and Doug Letto, a retired journalist who had spent three decades at CBC News, most recently as senior producer for the province’s popular dinner-hour newscast, Here & Now.

Mr. Wells and Ms. Stoddart declined interview requests, but Mr. Letto agreed to speak with The Globe about the process.

“A big reason that the committee was struck was that the public had lost confidence in the act and their ability to access public information,” he says. “It had become an access to information act in name only at that point.”

According to Mr. Letto, the controversy over Bill 29 was tied directly to another political debacle: the continuing delays and cost overruns for the hydroelectric project at Muskrat Falls, a complex infrastructure development in the Labrador region. Originally approved in 2012 at a $7.4-billion price tag, it was completed this past April – years behind schedule – and ultimately cost more than $13-billion. A 2020 public inquiry called the undertaking a “misguided project.”

“There was a sense that the public didn’t have access to all the information,” Mr. Letto says, “and probably a suspicion that things were being held from the public because costs were going to be much higher, or the project wasn’t as sound and viable as the government had professed in public that it would be.”

Retired journalist Doug Letto was part of the committee set up to review Bill 29.Alex Spracklin/The Globe and Mail

From the start, the committee knew it had to hold public hearings, Mr. Letto recalls. Bill 29′s changes had been government-driven; this review had to be the opposite. Over the summer of 2014, the trio received more than 60 written submissions and held 10 days of public hearings, in which it primarily heard from the two groups that most use access laws in Canada: the public and businesses.

During one hearing, the committee heard from Barry Tilley, then-president of office supplies business Dicks and Company Basics. In 2011, Dicks had bid – and lost – a contract to provide Memorial University’s office supplies. The company later learned that a Staples subsidiary had underbid the next cheapest offer by a whopping 42 per cent. (In fact, Staples had been Memorial University’s sole supplier for 28 years straight, according to Dicks’ submission to the committee.) Curious about how Staples could possibly afford this, Dicks filed access requests, but Staples didn’t allow Memorial University to disclose some of the information.

“Heightened competition is not a harm that should be protected” by access law, Mr. Tilley wrote to the committee.

(Memorial subsequently decided to release the documents. Staples took the university to court, lost, appealed and lost again. Kathleen Stelmach, a Staples spokesperson, said that the information was ultimately provided to Dicks.)

In another case, a journalist testified that municipalities were redacting information from documents tabled at council meetings, making it “impossible to know who was promoting land developments or other projects,” the committee later wrote in its report.

“To me, the act was being applied in a perverse way,” Mr. Letto says in his interview with The Globe. “Citizens should be able to get basic information about what happens in their community.”

As the hearings went on, Mr. Letto came to see a pattern appearing repeatedly: the government’s ingrained risk-aversion, and the intrinsic secretiveness that follows.

“Politicians and bureaucrats are not really interested in the public knowing what’s really happening inside the government,” he says. “That just adds to a really risk-averse environment. There’s always tremendous pressure inside the government to tweak the rules so that there’s less of a chance that what they would see as damaging material is released.”

Ex-premier Clyde Wells, shown in 2018, was instrumental in pressing for new access legislation, Mr. Letto says.Paul Daly/The Canadian Press

The committee’s final report in March, 2015 – a 491-page tome with 90 recommendations – called for the dismantling of the changes made by Bill 29. But it also went further, drafting an entirely new access law for Newfoundland.

Mr. Wells, the committee’s chair, was “determined from the beginning that we actually create a piece of draft legislation,” Mr. Letto recalls. “His long experience in government had told him that if you give a recommendation to somebody and you’re not specific about what it is, it can be interpreted a dozen ways to Sunday, and how it shows up in the end may not be at all how you planned to do it.”

That draft bill made various innovative changes.

The filing fee for an access request, which had been $5, was eliminated entirely. Processing fees were also drastically overhauled. Under the old regime, the first four hours spent processing a request were free; after that, public bodies could charge $25 an hour. Instead, the committee said the first 10 to 15 hours should be free, covering off the vast majority of requests. Only highly complex requests would incur any kind of fee at all.

Timelines were also tightened: Institutions now had 20 business days to respond to a request instead of 30 calendar days. More importantly, however, institutions could no longer claim time extensions on requests unilaterally, as is the case in every other Canadian jurisdiction. Instead, they would have to ask the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner – the office now overseen by Mr. Harvey – to approve time extensions.

Under Newfoundland’s law, information commissioners like Mr. Harvey have an array of powers to help them challenge public bodies.Alex Spracklin/The Globe and Mail

The commissioner’s position was also reimagined.

For one, their term of office was changed. Previously, commissioners had two-year terms, a short time frame that encouraged them to find favour with the government if they wanted to be reappointed, Mr. Letto says. The committee recommended a six-year term instead.

Before the committee’s reforms, commissioners had 120 calendar days to close out an access complaint, but only hit that deadline about 10 per cent of the time. This deadline was shortened to 65 business days, or 13 weeks.

But the commissioner was also given new powers. Equivalent offices in many other Canadian jurisdictions have the court-like ability to order a public body to conduct a search, modify a fee or release documents. In Newfoundland, however, the commissioner did not have these “order-making” powers; they could only recommend that the institutions take certain actions.

The committee proposed giving the office a novel “hybrid” power. The commissioner would still issue recommendations, but if an institution wanted to disregard them, it would need to go to court and make its case. In practice, this meant recommendations would effectively become binding orders, since most public bodies wouldn’t want to invest the money and time necessary to take an access dispute to court.

This was a small tweak with enormous impact. During most access disputes in other Canadian jurisdictions, the person appealing has to prove to an appeals body – and perhaps, eventually, a court – that they are correct. The committee reversed that burden, saying that public bodies were the ones that had to prove they’d made the right call.

“It was a shifting of the onus from the applicant,” Mr. Letto says, “to the organization that holds the information, or is in a position to block it being released.”

Combined, these changes transformed the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner into a much more efficient operation, employing what the commissioner, Mr. Harvey, calls the “quick-and-dirty approach.”

Because the office had strict deadlines, it could not ponderously consider complaints for years on end. And, because it wasn’t issuing orders, it didn’t need to spend time writing ironclad, inscrutable legalistic decisions several thousand words long – in stark contrast to the timelines and decisions from commissioners in places such as Ontario and British Columbia.

The government responded on the same day the committee made its final report public. Paul Davis, then-Progressive Conservative premier, said he would accept all recommendations. In fact, he said he would introduce the committee’s draft bill at the House of Assembly. “I am confident this will become an innovative model for the rest of the country,” Mr. Davis said in a statement at the time.

Bill 1, unchanged aside from a typo and a small clarification, became Newfoundland and Labrador’s new access law that summer.

“If you were to create the perfect situation for this sort of thing to get under way – with an independent committee, draft legislation, and then the government saying, ‘We’re going to implement it’ – I mean, you couldn’t ask for a better alignment of the circumstances for that to take place,” Mr. Letto says.

Investigative journalist Robyn Doolittle has filed many freedom of information requests in her work. Here’s what you need to know about the process.

The Globe and Mail

Toby Mendel, executive director of the Centre for Law and Democracy, a Halifax-based human-rights organization that scores and ranks the world’s access laws, says that Newfoundland’s sweeping reforms were only possible because access to information had “political traction” – and because the government knew the law could benefit it, too.

By the time the bill was passed, an election was less than six months away, and the current government’s odds were bleak. In a poll conducted in June, 2015 by Abacus Data, the provincial Liberals held 42 per cent of voter support. The Progressive Conservatives trailed 25 points behind, at 17 per cent.

“Governments which have a little bit more foresight understand that they’re only going to be in government for a while, and then they’re going to be in opposition,” Mr. Mendel says.

Opposition parties are frequent users of access systems, which they use to hold governments accountable; in this case, he says, the government knew enhanced access could be useful if it lost the election.

The impact of Newfoundland’s new law is remarkable.

According to Mr. Mendel, the new law rocketed Newfoundland and Labrador into 23rd place globally on the Centre for Law and Democracy’s Global Right To Information rating scale, ahead of Sweden, Britain and New Zealand, and well ahead of any other Canadian jurisdiction. (The federal government’s law ranks 51st.)

“That’s an impressive gap,” Mr. Mendel says, “and you see that reflected in the way that the act delivers information for Newfoundlanders.”

According to annual reports, in the 2014-15 fiscal year the government gave itself more time to process access requests in 27 per cent of cases. In 2020-21, a few years after the system was overhauled, that happened just 8 per cent of the time, meaning almost all requests were completed within 20 business days.

In 2014-15, the access system charged $3,861.25 in filing and processing fees and received 628 access requests. In 2020-21, no fees were charged. The Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner closes all its access complaints within its legislated timeline of 13 weeks, and has no backlog.

Crucially, the public is also now engaging more with access to information. Since 2015, the number of access requests has seen explosive growth: In 2022, institutions received 3,341 requests, 432 per cent more than in 2015.

Many of those new requests are coming from individuals – not the media, businesses or political parties – who accounted for 61 per cent of all requesters in 2021. In 2015, they accounted for just 31 per cent of the total.

Newfoundland’s access reform is not a panacea. Now that the law has been enhanced and modernized, the pendulum of transparency may once again begin swinging back toward opacity, warns Mr. Harvey, the province’s Information Commissioner.

“I think it’s reasonable to expect that you can’t rely on those things to hold forever, and that you need periodic reinvigoration,” he says. “You need to be vigilant.”

At the province’s first review of the law since 2015, various government institutions told the reviewing committee that they were now overloaded with access requests.

“This is a good problem to have, that your citizenship is engaged,” Mr. Harvey says.

The final report contains more than 100 recommendations, including reintroducing the concept of “vexatious requesters,” altering how third-party business information is handled, new exemptions for certain kinds of legal information and changing fees for complex requests. The government has yet to bring amendments to the House of Assembly for consideration.

The saga of access to information reform in Newfoundland goes beyond a committee and a new law. Becoming a world-class access jurisdiction required cultural change, too. After all, other Canadian jurisdictions have similar laws – and public bodies break them all the time.

“If your question was, ‘What changed to improve legislative compliance after 2015?,’ I think the answer would be: Leadership comes from the top,” Mr. Harvey says. “And at that time, under both the senior bureaucratic leadership and the political leadership, that’s a message that was sent.”

When an institution runs afoul of the law, Mr. Harvey is willing to wield the power of his office through media appearances, an arena the government pays close attention to. Access laws are “politically operating statutes,” he says. Thus, the penalties themselves must be political – through embarrassment, for instance.

“I am under no illusions that I don’t operate in a political milieu,” Mr. Harvey continues. “There is no question that, while I am not a politician, I am a political actor, whether I want to be or not. If I thought that this was a purely bureaucratic situation that operated entirely impartially, that would be naive.”

For the time being, Mr. Harvey may be the only commissioner in the country that is satisfied with the tools at his disposal.

“It’s marvelous to be in a job where I feel like I have the resources to do my job,” Mr. Harvey says. “I’ve never felt like that before.”

Secret Canada: More from The Globe and Mail

Podcast: Tom Cardoso on The Decibel

The lion’s share of federal access-to-information request are from immigration applicants left in the dark about the status of their cases. Tom Cardoso explains how that happened and why things will likely get worse. Subscribe for more episodes.

Reader callout: Share your FOI stories

Have you ever filed a freedom of information request in Canada? What was the process like for you? The Globe wants to hear from Canadians about what they've encountered. Share your story below or e-mail secretcanada@globeandmail.com