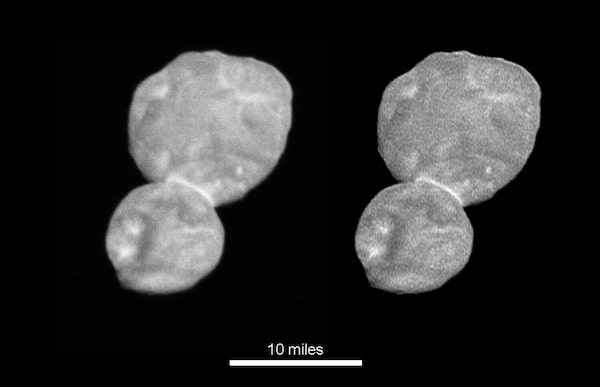

This image made available by NASA on Wednesday, Jan. 2, 2019 shows the size and shape of the object Ultima Thule, about 1 billion miles beyond Pluto. The New Horizons spacecraft encountered it on Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019. (NASA via AP)The Associated Press

NASA’s New Horizons mission has begun streaming its precious data bit by bit across more than 6.6 billion kilometres of interplanetary space to gradually reveal the frozen face and character of the most distant object a spacecraft has ever explored.

Delighted mission controllers confirmed that the robotic explorer survived its encounter with Ultima Thule early Tuesday morning and had started transmitting the images and data it gathered during the historic flyby.

Scientists said the information gleaned from the remote celestial object, thought to be an unchanged relic from the solar system’s distant past, could provide clues to how the planets formed.

The first indication that the spacecraft was safe came at 10:33 a.m. ET, exactly 10 hours after it sailed past Ultima Thule.

The transmission broke a tense moment of silence as science team leaders who have been with the New Horizons project for more than two decades waited for their first contact since the flyby. It was hardly a foregone conclusion that the probe would even be able to transmit: With a cruising speed of 14.4 kilometres per second, a collision with the smallest of pebbles would destroy it.

Scientists, engineers, their families and others who gathered to mark the event at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, erupted in cheers as mission controllers announced that New Horizons had phoned home as scheduled.

The night before, after ringing in the new year, team members had counted down and celebrated the moment they expected New Horizons would make its closest approach to its target based on their knowledge of its trajectory.

But despite the festive atmosphere — which included the release of a New Horizons song recorded by contributing scientist and rock guitarist Brian May of Queen, who was on hand for the event — the mission team had no way of knowing if their spacecraft was still in one piece and executing its reconnaissance of Ultima Thule.

The feat has been compared to photographing a flower by the side of the road from the window of a speeding car at night.

Before mission controllers could be certain New Horizons succeeded, the spacecraft had to pause its data gathering and rotate to point its main antenna back toward home. The signal then required more than six hours to cross the vast distance between Ultima Thule and Earth.

“This mission has always been about delayed gratification,” principal investigator Alan Stern joked during a news briefing on Tuesday morning.

Proposed in the early 1990s, New Horizons was launched in 2006, and in 2015 became the first spacecraft to reach Pluto. The visit to Ultima Thule means it has delivered on the second half of its mission, which is to provide the first closeup investigation of a member of the Kuiper Belt, a vast region of small, frozen bodies that ply the twilight darkness far beyond the major planets of our solar system. The challenge was all the greater because scientists did not yet have a suitable Kuiper Belt object in mind when New Horizons was launched. Ultima Thule was discovered in 2014.

Because of the extreme distance and slow transmission rate, scientists do not expect to have a good view of Ultima Thule to share until Wednesday after they have worked with the raw data.

“Ultima Thule will be turned into a real world,” team member and planetary scientist Hal Weaver said.

On Tuesday, scientists released an image that was taken before the closest point of the approach that revealed Ultima Thule is likely to be a bowling pin-shaped object about 35 kilometres long by 15 kilometres at its widest. The pixelated image does not exclude the possibility that Ultima Thule is really two objects in close proximity or in contact.

Stephen Gwyn, an astronomer and data specialist with Canada’s National Research Council who is participating in the mission, said the image has already solved one mystery: how the oblong-shaped Ultima Thule can rotate without changing its brightness.

The answer is one that scientists already suspected: Ultima Thule’s spin axis is roughly pointed toward Earth, so that it appears somewhat like a turning propeller with the illuminated side constantly facing earthbound telescopes.

“The data that we’ve got so far shows that we were right. What we’re going to get next is the stuff that we didn’t expect,” Dr. Gwyn said. “This thing is going to look cool.”

Dr. Stern added that while this week’s images should be a dramatic improvement over what is currently known about the Kuiper Belt, scientists will not have their best views downloaded until February.

By then, New Horizons will be on its way out of the solar system to roam the Milky Way galaxy for eternity, a fact that mission operations manager Alice Bowman said has stayed with her through the tension and excitement of the once-in-a-lifetime flyby.

“There’s a bit of all of us on that spacecraft that will continue after we’re long gone here on Earth,” she said.