National Film Board producer Lorraine Monk on July 9, 1981.John Wood/The Globe and Mail

Lorraine Monk was the most powerful woman in the world of Canadian photography, a determined and steely presence at the National Film Board in Ottawa.

Starting in the early 1960s with a budget of $85,000 and a staff of 10, she created hundreds of circulating exhibitions, a Canadian contemporary photography gallery and dozens of glossy books such as Canada: A Year of the Land, Call Them Canadians and Canada with Love/Canada avec amour celebrating the landscapes and peoples of this country.

The endless photographic projects she dreamed up as executive producer of the NFB’s Still Photography Division gave employment to legions of photographers whom she sent across the country at government expense, enabling them to make a living while finding their own pictorial language.

She created a vast collection of photographs (some 160,000) that are now housed in the National Gallery of Canada, a part of our artistic patrimony. Her books embodied what Carol Payne of Carleton University, in her history of the Still Photography Division The Official Picture, called a “banal nationalism.”

Martha Langford, professor of art history at Concordia University and a former NFB colleague, recalls: “Lorraine had engineered many photography projects that people thought impossible. One of her great talents was identifying opportunities for the division to gain national attention and benefit financially – benefits that were passed on to the photographic community.”

She cites Between Friends/Entre Amis, Canada’s gift to the U.S. at their bicentennial in 1976, as an example. “It gave assignments to many Canadian photographers and generated income for the division’s future projects, as most of the bill was paid by what was then called External Affairs.”

Ms. Monk’s career in Ottawa coincided with a boom in photography in the 1970s as the public began to perceive that photographs were not merely vehicles of information or reportage but a means of personal expression and a collectible art form. It was an exciting period, before the introduction of digital photography and cellphone cameras took much of the mystique out of photography.

Notable Canadian photographers whom she helped and encouraged include John Reeves, Freeman Patterson, John Max, Nina Raginsky, John de Visser and Thaddeus Holownia.

“She had a great eye, great judgment,” said veteran publisher Anna Porter, editor-in-chief at McClelland & Stewart during the publication of some of Ms. Monk’s books. She recalled that Ms. Monk’s perfectionism created havoc: “There were people at M&S tearing their hair out [but] Between Friends became the gift book of the decade.”

Ms. Monk died on Dec. 17 at a Toronto nursing home of multiple infections, aged 98.

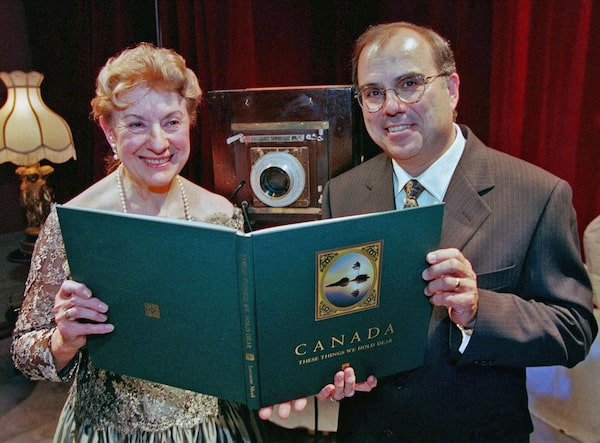

Lorraine Monk and Kodak Canada's president, Norman W. Naumoff, marked the company's 100th Anniversary at an evening gala event held on Oct. 28, 1999.Derek Oliver/Kodak Canada / Canada News Wire

Lorraine Althea Constance Spurrell was born in Montreal on May 26, 1922, the third of four children of Edwin and Eileen Spurrell, both Newfoundlanders. Her mother, orphaned as a child, was raised in the home of her uncle, the Anglican archbishop of Newfoundland, who sent her to “ladies’ college” to be educated, while Edwin was a cod fisherman who could barely read.

As a teenager, Edwin had fought in the trenches of the First World War and was gravely injured; upon recovering, he was invited to tea in Buckingham Palace with Queen Mary and King George.

Eileen taught him to read and he became something of a philosopher, while working as an executive of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

’'My mother worshipped her father,” recalled Karyn Monk, Lorraine Monk’s younger daughter.

The only boy in the Spurrell family was a little brother, Grant, who died of meningitis at age 5. “His death devastated the family,” according to Karyn. “My mother remembered that my grandfather used to sing Danny Boy and always ended by crying. She knew that he was thinking then of Grant. She told us, ‘I always tried to please my father and make him proud. And I told him: “I will be your son.” ’ ”

She was the first in the family to go to university when she enrolled at McGill to study art history and sociology, obtaining a BA in 1944 and an MA in 1946. She embarked on a doctorate, but had to drop out when she fell ill with tuberculosis a year later.

After recovering, she married her childhood sweetheart, Lloyd Hackwell, whose movie-star looks attracted many women. At the age of 27, she gave birth to a baby girl, Leslie, but soon after, the couple divorced. A single mother needed to work, but only secretaries were wanted so Lorraine faked shorthand and typing skills. She moved in with her parents, who looked after the baby while she worked.

The search for work opportunities eventually took her to Ottawa, where she landed a government job writing the history of the Canadian Navy during the Second World War.

In 1957, she was hired by the NFB to write captions for photo stories about Canada. These stories were placed with local magazines and newspapers by Canadian embassies and consulates around the world and reached more than 30 countries, including some behind the Iron Curtain.

Three years later, she was appointed executive producer of what was then called Photo Services, which had a mandate to provide photographs to government departments on request. Gradually, she altered the mandate and unilaterally changed the name to the Still Photography Division of the NFB. She fired all but two of the staff photographers and developed ties to Canada’s growing number of freelance photographers, whose commissioned photographs she purchased, including the copyright.

During her early Ottawa days, she reconnected with John Monk, whom she had first met at McGill University. “My father was injured in the Second World War, and had shrapnel in his body; he walked with a cane,” daughter Karyn explained. “He was brilliant, loved to read and was a great storyteller. He had stayed in Europe after the war and reported on the radio from Amsterdam; he ended up briefly marrying a Dutch woman, who would not give him a divorce. He and my mother had to wait a long time before they could marry.”

Once married, they wasted no time. Three children arrived: John in 1958, David in ’59 and Karyn in ’60. Maternity leave was unknown then, and Lorraine Monk went back to work two weeks after each birth. With her husband studying to become a lawyer, she couldn’t afford to lose her job.

But that marriage, too, ran aground. After a long separation, John Monk died about a year before Ms. Monk left Ottawa in 1980.

She next devoted her energies to creating a Canadian photography museum in Toronto, with satellite museums in other cities. In the early ’80s, she lost a chunk of the funds she had raised to Albert Rosenberg, dubbed “the Yorkville Swindler,” who drew her into a scheme to buy a Picasso and resell it at a profit. At his trial, Ms. Monk reportedly testified that she was so distraught by this loss, she had considered suicide.

She mounted an exhibition in 1987 of the work of Richard Harrington, which revived interest in his tragic pictures of the caribou famine that afflicted the Inuit from 1947 to 1952. The exhibition was billed as the first show of the Canadian Museum of Photography, but the museum did not exist; the show was held at the Royal Ontario Museum.

In Ottawa, the similarly named Museum of Contemporary Canadian Photography (affiliated with the National Gallery of Canada) already existed but she believed her museum had to be in Toronto. “The Ottawa museum was not her vision,” her daughter recalled.

In 1998, she joined the board of the Roloff Beny Foundation (Mr. Beny, her close friend, had died in Rome in 1984) and used her position to support the photographic community. She created a lavish prize for best photo book of the year, which continued till 2004.

She went on devising photo books that won awards for their production values including Photographs that Changed the World (1989) and Canada: These Things We Hold Dear (1999). She was invested as an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1983, and had honorary degrees from York University and Carleton, as well as an Order of Ontario (2007) and the Queen’s Golden Jubilee medal (2002).

She remained a romantic, marrying for the last time in 2010 when she was in her 80s. Her husband Daniel Fernandez, a musician and composer, remained devoted to her till the end, visiting her regularly at the nursing home where she spent the past seven years after a broken hip three years after their wedding.

She was an inspiration for women in the arts, such as Vancouver artist Althea Thauberger who in 2015 created a video installation for the Musée d’art contemporain in Montreal in which she re-enacts the young Lorraine Monk of the 1960s at her desk surrounded by photographs.

Lorraine Monk was predeceased by her sister Shirley, and leaves her other sister June, her husband Daniel Fernandez, four children, Leslie, John, David and Karyn and eight grandchildren.