:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ZUHXFQ6UNNJ6FKEGAYXYL33DHM.JPG)

A multicoloured seascape of glowing gas and dust that is the chaotic cradle of new born solar systems. An intricate bubble blown into space by a dying star. A slow motion pile up of galaxies that reveals the hidden architecture of disruption. A cosmic magnifying glass that uses a massive concentration of matter to probe to the limits of the visible universe. And an undulating string of data points that bears the signature of water vapour in the atmosphere of a distant world.

With one striking view after another, the newly commissioned James Webb Space Telescope has signalled an epochal shift in astronomers’ capacity to observe and understand our universe.

First and foremost, this week’s release of the first colour images from Webb confirms its quintessential ability to perceive targets that are farther and fainter than any telescope has seen before. But they also show it to be a versatile engine of discovery that can be applied to wide range of cosmic mysteries.

“We’re turning the page on many, many new chapters in astrophysics. Everything is going to change completely,” said René Doyon, a professor of astronomy at the University of Montreal and principal investigator with the Canadian Webb science team.

The Decibel: How the James Webb Space Telescope will take us back in time

Canada’s role in developing and building one of the Webb’s four science instruments will give the country’s scientists a guaranteed share of time on the telescope. The European Space Agency is also a partner. But NASA is the primary driver and bill-payer of the US$10-billion project, and it was the American space agency that led Webb’s public debut, more than six months after the new telescope was launched.

Events got under way on Monday afternoon with a ceremonial unveiling of a first image by U.S. President Joe Biden.

Galaxies far away and long ago

The debut photo of a massive cluster of distant galaxies bending the light of objects in the background was a quintessential demonstration of Webb’s ability to perceive targets that are farther and fainter than any telescope has seen before.

The photo shows the distant cluster of galaxies SMACS J0723.3-7327, a cosmic magnifying glass about five billion light years away that is warping and amplifying the view of more distant galaxies at outer edges of the visible universe.

Deep field composite images of the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723, from the Mid-Infrared (left) and Near-Infrared instruments of NASA's James Webb Space Telescope.NASA/Reuters

The unveiling continued on Tuesday morning with four additional releases. In addition to their visual appeal, the five celestial objects selected for Webb’s initial round of observations show off the telescope’s full suite of capabilities, including contributions from each of its science instruments operating at different bandwidths.

All of them are in the infrared part of the spectrum, which the human eye cannot see but which is ideal for studying objects in the distant universe and nearby phenomena, such as the birth of new stars, that are typically hidden behind curtains of interstellar dust.

The Carina Nebula

A vast star-forming region in our Milky Way galaxy located 7,500 light years away.

The "Cosmic Cliffs" of the Carina Nebula. The image is divided horizontally by an undulating line between a cloudscape forming a nebula along the bottom portion, and a comparatively clear upper portion. Speckled across both portions is a star field, showing innumerable stars of many sizes.NASA/Reuters

A landscape of mountains and valleys speckled with glittering stars which is actually the edge of a nearby, young, star-forming region called NGC 3324 in the Carina Nebula. This image reveals previously invisible areas of star birth for the first time by combining information captured by the Near-Infrared Camera and the Mid-Infrared Instrument.Supplied/AFP/Getty Images

The Southern Ring Nebula

A luminous shell of gas, 2,000 light years from Earth that was expelled from a dying star and etched with a spirograph-like pattern by an orbiting companion.

The Southern Ring Nebula in near-infrared light, at left, and mid-infrared light, at right. In the Near-Infrared Camera image, the white dwarf appears to the lower left of the bright, central star, partially hidden by a diffraction spike. The same star appears – but brighter, larger, and redder – in the Mid-Infrared Instrument image. This white dwarf star is cloaked in thick layers of dust, which make it appear larger.NASA/Reuters

Stephan’s Quintet

An iconic grouping of five galaxies, four of which are in a tangle of complex gravitational interactions unfolding at a distance of 290 million light years.

A composite of near and mid-infrared data shows a group of five galaxies that appear close to each other in the sky: two in the middle, one toward the top, one to the upper left, and one toward the bottom.NASA/Reuters

The results – met with superlatives from across the astronomical community – show that the telescope’s science mission is already under way, with a cascade of data expected to start rolling out to researchers on Thursday.

“The world’s vehicle for deepest space exploration is open for business – all aboard,” said Eric Smith, chief scientist for NASA’s astrophysics division, during a Tuesday news briefing at the Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland.

Indeed, so great are the quality and quantity of information that is evident in Webb’s first images that the milestone carries historic significance as part of a broader saga of scientific development.

It’s been 412 years since Galileo turned a small tube with glass lenses toward the night sky and showed there is more to the heavens – so much more – than the eye alone can perceive.

Since then, the tabletop device gave way to massive conduits of light that reached above the rooftops to grasp at the starry firmament. In Greenwich, Paris and beyond, new temples of observation were constructed for professional sky watchers, who no longer preoccupied themselves with casting horoscopes but with discerning the grand machinery of creation.

From cities to mountaintops the telescope was hauled, by mule team and flatbed truck. It sprang from the wooded slopes of California to the sky-punching heights of Hawaii and the Andes.

Then it left Earth altogether, launched into orbit to become a celestial object in its own right, even as it carried humanity’s gaze billions of light years farther into outer space.

Now, a new rung has been added to the telescope’s remarkable ascent, ushered in by an instrument in Webb that can penetrate to the most distant reaches of the observable universe and address some of the most fundamental questions ever asked about the cosmos – including how the first stars and galaxies formed, and whether life exists beyond Earth.

That latter question was evoked by the only release this week that did not include an image.

The spectrum of WASP-96b

It is a spectrum obtained by analyzing the light filtered through the atmosphere of a planet as it crossed in front of the star it orbits. The result confirms the presence of water molecules in the atmosphere.

A light curve from Webb’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph shows the change in brightness of light from the WASP-96 star system over time as the planet transits the star. A transit occurs when an orbiting planet moves between the star and the telescope, blocking some of the light from the star.NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI/Supplied

The planet, known as WASP-96 b, is a gas giant about half as massive as Jupiter but far hotter because of its close proximity to the star. That makes it a highly unlikely place to harbour life, but the same technique can now be applied to a wide range of planets and could conceivably turn up indirect evidence of it if there is any to be found.

“We’ll be looking for ozone, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and all these different signatures that tell us interesting things about what could be producing them on the planet – whether it’s volcanism, a chemical reaction, a geophysical reaction or maybe a biological reaction,” said Nathalie Ouellette, an astrophysicist with the University of Montreal’s Institute for Research on Exoplanets.

A transmission spectrum made from a single observation using Webb’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph reveals atmospheric characteristics of the hot gas giant exoplanet WASP-96 b.NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI

Dr. Ouellette added that Webb’s storied predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope, was launched years before large numbers of planets were detected orbiting other stars in our galaxy, so it was never optimized for observing them. Webb is a different story, and exoplanets is one area where Canadian researchers aim to make a mark with it, aided by the hardware Canada has provided.

Sarah Gallagher, a professor of astronomy at Western University in London, Ont., and science adviser to the Canadian Space Agency, said she was particularly struck by Webb’s view of Stephan’s Quintet, which she has studied.

The galaxies were imaged by two of Webb’s instruments – one showing a view that is relatively similar to what the eye would see, the other showing how they appear when dust is stripped away and shock waves and other structures resulting from the motions of the galaxies are apparent.

“I think what’s so exciting is that already we can see unexpected things,” Dr. Gallagher said.

Over all, astronomers have commented widely on two of the characteristics of the Webb images that make them different from those produced by Hubble. The first is the disorienting effect of looking at the universe in infrared light, but with a sharpness and level of detail that previously has only been known in optical photos. The second is a sense that the photos are crowded with information because Webb’s large primary mirror can gather so much more light than Hubble.

Jayanne English, an astronomer and imaging specialist at the University of Manitoba who was involved in preparing some of Hubble’s most celebrated portraits of celestial objects, said Webb is part of an era in which the study of the cosmos is moving beyond the narrow range of wavelengths that are visible to the eye – a development that will call for creative use of visualization to help scientists understand what they are seeing.

“These visualizations guide our measurements and evolving theories, they confirm or eliminate scientific postulates, and they lead to serendipitous discoveries and new ideas,” Dr. English said.

But if there was a sentiment that most powerfully expressed the impact the images may have beyond the research community, it was stated in Tuesday’s briefing by Webb operations project scientist, Jane Rigby, who said the telescope gave her a feeling of pride in humanity, and of “people in a broken world managing to do something right, to see some of the majesty that’s out there.”

Shots in the Dark: A brief history of the astronomical image

Since the invention of the telescope, astronomers have sought to capture what the universe looks like when magnified beyond the limits of human seeing. The result has been a step-by-step evolution in cosmic perspective.

Drawing Light

William Parsons/Supplied

Before photography, it took a patient hand working in the dark with pencil or pen to capture astronomical details as seen through the eyepiece of a telescope. Large telescopes, which gather more light, are best at revealing faint and diffuse celestial objects. In 1845, William Parsons, the 3rd Earl of Rosse, used what was then the world’s largest telescope at Birr Castle, Ireland, when recording the spiral pattern he saw in a small patch of light called M51, later known as the Whirlpool Galaxy.

The Camera Comes of Age

NOIRLAB/NSF/AURA/Supplied

Combining telescopes with cameras gave astronomers a more objective and very different way of visualizing the night sky. Instead of being limited to the nearly instantaneous view of the eye, a photograph could be taken with a long exposure, allowing light to gradually reveal more information about distant targets. This photo of the Whirlpool Galaxy was taken at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, in 1975. Although black and white images tend to yield sharper results on photographic plates, astronomers could also obtain colour information shooting in black and white through different colour filters.

Above The Clouds and Digital

NASA/ESA/S. Beckwith(STScI)/The Hubble Heritage Team/Supplied

The late 20th century brought two big developments to astronomical imaging. The first was the development of the CCD chip, which removes the need for light-sensitive chemicals used in traditional photography in favour of fully electronic imaging. The second was the ability to place telescopes in space, which eliminates the distorting effect of air turbulence on incoming light from the heavens. From the outset, the Hubble Space Telescope was intended to leverage both of these breakthroughs to provide images of unprecedented clarity and depth. Launched in 1990 and upgraded several times, Hubble was at peak performance in 2005 when it provided this image of the Whirlpool Galaxy.

Extending The Spectrum

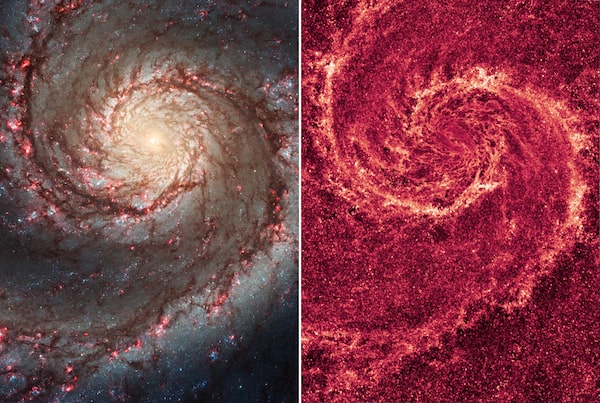

Left: Optical view of the Whirlpool Galaxy. Right: Infrared view.NASA/ESA/Supplied

Moving to space allows telescopes to see in wavelengths that are invisible to the eye and blocked by the atmosphere, including ultraviolet and much of the infrared part of the spectrum. This view of the central region of the Whirlpool Galaxy compares two of Hubble’s cameras, one working at optical wavelengths and one in infrared. The optical view highlights bright stars, which have a bluish tinge, and pink clouds of ionized hydrogen gas in the galaxy’s spiral arms. In the infrared view is the galaxy’s dust clouds, where new stars are born, that are most prominent. Webb is designed to see mostly in infrared, though more sharply than Hubble because of its larger size.

How Webb Sees the Universe

First proposed more than 30 years ago as the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, Webb is the largest and most powerful space observatory ever built.

2

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Primary mirror

Almost six times bigger than Hubble’s, 18 gold-plated beryllium hexagons give much greater light-gathering capability

1

Secondary mirror

Reflects light from primary mirror into science instruments

2

Sunshield

Tennis court-sized layers block light from sun, moon and Earth to keep telescope at -223C, essential to see faint infrared light without interference

3

Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM)

Light reflected off the telescope's mirrors can be directed to four science instruments to create images or spectra (analysis by separating light into different wavelengths)

4

Spacecraft bus

Controls power and other support systems

5

Spacecraft bus Control, power and other support systems

6

Earth-pointing antenna

7

Solar power array

8

Trim flap

Helps stabilize satellite

9

SIZE COMPARISON TO THE HUBBLE TELESCOPE

James

Webb

6.5m

Hubble

2.4m

TIME MACHINE

Because it takes time for light to travel across space, more distant objects are seen at earlier times in cosmic history. At its farthest limit, Webb can see what the universe looked like a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a time when galaxies were just beginning to form.

Visible

UV

X-rays

Infrared

Radio waves

James

Webb

Hubble

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GRAPHIC NEWS

2

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Primary mirror

Almost six times bigger than Hubble’s, 18 gold-plated beryllium hexagons give much greater light-gathering capability

1

Secondary mirror

Reflects light from primary mirror into science instruments

2

Sunshield

Tennis court-sized layers block light from sun, moon and Earth to keep telescope at -223C, essential to see faint infrared light without interference

3

Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM)

Light reflected off the telescope's mirrors can be directed to four science instruments to create images or spectra (analysis by separating light into different wavelengths)

4

Star trackers

Help to keep telescope pointed at target

5

Spacecraft bus

Controls power and other support systems

6

Earth-pointing antenna

7

Solar power array

8

Trim flap

Helps stabilize satellite

9

SIZE COMPARISON TO THE HUBBLE TELESCOPE

James

Webb

6.5m

Hubble

2.4m

TIME MACHINE

Because it takes time for light to travel across space, more distant objects are seen at earlier times in cosmic history. At its farthest limit, Webb can see what the universe looked like a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a time when galaxies were just beginning to form.

Visible

X-rays

UV

Infrared

Radio waves

James

Webb

Hubble

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GRAPHIC NEWS

Primary mirror

Almost six times bigger than Hubble’s, 18 gold-plated beryllium hexagons give much greater light-gathering capability

Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM)

Light reflected off the telescope's mirrors can be directed to four science instruments to create images or spectra (analysis by separating light into different wavelengths)

Secondary mirror

Reflects light from primary mirror into science instruments

Trim flap

Helps stabilize satellite

Sunshield

Tennis court-sized layers block light from sun, moon and Earth to keep telescope at -223C, essential to see faint infrared light without interference

Solar power array

SIZE COMPARISON TO THE HUBBLE TELESCOPE

Earth-pointing antenna

James

Webb

6.5m

Spacecraft bus

Controls power and other support systems

Hubble

2.4m

Star trackers

Help to keep telescope pointed at target

SEEING INFRARED

Webb can perceive of wavelengths of light that are longer than Hubble or the human eye can see. This infrared part of the spectrum is ideal for exploring to the edge of the visible universe or for looking at solar systems forming within our own galaxy.

X-rays

Ultraviolet

Visible

Infrared

Radio waves

James

Webb

Hubble

TIME MACHINE

Because it takes time for light to travel across space, more distant objects are seen at earlier times in cosmic history. At its farthest limit, Webb can see what the universe looked like a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a time when galaxies were just beginning to form.

Hubble

James

Webb

First galaxies

13.8

(Today)

12

9

6

3

0

(Big Bang)

Age of universe (billions of years)

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GRAPHIC NEWS

Learn more about the James Webb Space Telescope

The James Webb Space Telescope is almost certain to make new discoveries with its huge mirror array. Science reporter Ivan Semeniuk outlines what makes Webb special, and ponders the cultural impact its first pictures will have on audiences used to vistas from the Hubble Space Telescope and GCI-heavy movies.

The Globe and Mail

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.