Conrad Johnson works out in the gym of the Stan Daniels Healing Centre in Edmonton. He arrived here after a decade in prison for a gang-related killing committed when he was 15.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

Conrad Johnson entered prison a teenager, and figured he’d leave a dead man.

In 1995, he committed one of Winnipeg’s most shocking gang crimes, shooting 13-year-old Joseph Spence in the back with a sawed-off shotgun. He had mistaken the Grade 7 student for a rival gang member.

The murder of the innocent boy, known as Beeper, begged for retribution. Amid a crackdown on youth gangs, prosecutors tried Mr. Johnson, then 15 years of age, as an adult and a judge handed him a life sentence.

Once behind bars, rival gang members took their turn at payback. Violence became a means of survival. During one stint at Millhaven, a maximum-security prison in Bath, Ont., an inmate stabbed him 36 times, he said.

He lived. But he wasn’t sure he wanted to.

A short time later, in 2005, he met with a prison psychologist who encouraged him to apply for residence at Stan Daniels Healing Centre. Mr. Johnson, who is Cree, had never heard of a healing lodge – a made-in-Canada idea hatched in the late 1980s in response to rising rates of Indigenous incarceration – but he was willing to try anything to escape pen life. The concept involved surrounding Indigenous offenders with Indigenous culture, traditional ceremonies and the constant guidance of elders.

He arrived at the Edmonton-based lodge as a 25-year-old, full of rage and resentment. Born to a mother imprisoned at Manitoba’s biggest youth detention centre before being shunted to the child-welfare system, he’d never engaged his First Nation roots.

He spent hours in a sweat lodge, smudged and worked with elders. The emphasis was on healing, not retribution.

And just like that, his violent streak ended.

“The way I see it, I was born right here in Stan Daniels,” says Mr. Johnson, now 42 years old. “I’ll always be grateful for this place.”

Mr. Johnson lifts weights with a hand tattooed with the names of his children.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

But he worries other Indigenous people won’t get the same opportunity. Lately, the Stan Daniels Healing Centre has been half empty, and it’s not alone. Through a review of documents and interviews with dozens of past and present corrections officials, healing lodge operators and residents, The Globe and Mail found similar healing lodges are underfunded and underused across the country, and remain scarce despite continued government commitments to build more.

Initially, the idea was for at least a couple dozen of the facilities to be built, but successive governments have failed to follow through despite the fact that lodges have been proven to lower recidivism rates. Today, there are only 10 of them in operation – and in total they are only 51 per cent occupied.

Although the original plan was to hand over control of all healing lodges from the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) to Indigenous leadership, four lodges are still run by the federal government. That leaves just 189 beds spread across six Indigenous-run lodges. Considering federal prisons hold around 4,000 Indigenous people, that’s roughly one bed for every 21 Indigenous prisoners.

Those six Indigenous-run lodges are still reliant on funding from the CSC, but they receive less money than other prisons – resulting in substantially lower pay for employees, fewer resources and inadequate infrastructure, according to staff.

Meanwhile, the overincarceration of Indigenous peoples only worsens. Although they constitute 5 per cent of Canada’s population, the share of federal inmates who identify as Indigenous has now soared to 33 per cent.

Despite that rise, and despite the fact that the Trudeau government has said addressing Indigenous incarceration is a top priority, the number of healing lodge beds has barely budged since his government gained power in 2015. Nor since Mr. Johnson first arrived at Stan Daniels 17 years ago.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/IZ55QPRGCFDAHK6YZOR2W5CYWI.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/O36UH4EFINDNDCQOTANW5EPW6M.JPG)

Federally incarcerated population

identifying as Indigenous

Per cent, since 2001

35%

2022: 33%

30

25

2001: 17.6%

20

15

10

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2000

2022

the globe and mail, Source: Office of the

Correctional Investigator

Federally incarcerated population

identifying as Indigenous

Per cent, since 2001

35%

2022: 33%

30

25

2001: 17.6%

20

15

10

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2000

2022

the globe and mail, Source: Office of the

Correctional Investigator

Federally incarcerated population identifying as Indigenous

Per cent, since 2001

35%

2022: 33%

30

25

2001: 17.6%

20

15

10

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2000

2022

the globe and mail, Source: Office of the Correctional Investigator

Since at least 1984, a series of federal task forces had grappled with the problem of how to address the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in prison. Compared with other populations, Indigenous prisoners tended to spend more time in high-security institutions and segregation cells. They were subjected to force more often and self-harmed with greater frequency. The task forces suggested an Indigenous-run prison could help the situation.

“There was a sense that First Nations wanted to become more involved because we saw so many of our people being sent off to faraway provincial and federal institutions,” said one of the task force members, Ed Buller, a member of the Mistawasis First Nation in Saskatchewan.

In 1992, the Mulroney government obliged, passing the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), which included a clause, Section 81, authorizing the Minister of Public Safety to contract out correctional services for Indigenous peoples to Indigenous organizations.

Three years later, Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge opened its doors on the lands of the Nekaneet First Nation in southwest Saskatchewan. It didn’t quite fulfill the vision laid out in the CCRA; the lodge was owned and operated by CSC. But corrections officials assured the community, and the media, that the facility would be transferred to First Nations control as soon as it was running smoothly.

There was much to admire at Okimaw Ohci. The site had been chosen by a circle of Indigenous advisers and carefully planned to reflect traditional beliefs. Buildings were arranged to resemble an eagle. Instead of a warden, the lodge had a kikawinaw, Cree for mother. There was a daycare, classrooms and coloured flags rather than fences to mark the perimeter. As a rule, the women-only facility had female guards, and no weapons available to staff. Forty Indigenous women were given eight months of training (compared with about 4½ months for CSC officers), focusing largely on First Nations, Métis and Inuit history and spirituality.

“We realized Indigenous women don’t have an opportunity to get her own history; we only get the Canadian history,” said Sharon McIvor, a member of the Lower Nicola Band in B.C. who led planning efforts for the lodge and remained with the facility until 2005. “And it was very successful for the time we were able to operate it the way we wanted to.”

Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge in Saskatchewan, as it looked in 1998.Kevin Van Paassen/Medicine Hat News/CP

By the time she left, Stan Daniels and several other healing lodges had been set up entirely under Indigenous control, fulfilling the promise of Section 81. As recently as 2005, CSC officials pledged that Okimaw Ohci would follow the same path and be transferred to Nekaneet control.

It never happened.

“And I can guarantee it never will happen,” said Patti Tait, co-acting executive director of the Elizabeth Fry Society of Saskatchewan, an organization advocating for imprisoned women in the province, and long-time counsellor and Indigenous liaison within the federal and provincial prison systems. “That was absolutely the intent to start. But now you have all the First Nations staff there being paid at the same rate as other CSC institutions. Reality is, if they convert to Section 81, it effectively becomes an NGO, and the money will be significantly lower than what they receive now.”

Larry Oakes, chief of Nekaneet around the time Okimaw Ohci opened, confirms Ms. Tait’s take, saying the community didn’t want “to go and negotiate at CSC’s table every few years” for funding.

And so the problem of having two tiers of healing lodges – the well-funded, CSC-run lodges, such as Okimaw Ohci, and underfunded Indigenous-run facilities, such as Stan Daniels – remains.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/QBRSVIMZGVFJXNCPHK5BRW4NM4.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/E3LZ4IC5TVAJ3M7VXFA2PW7T4I.JPG)

Despite its lower funding, Stan Daniels is a good example of why healing lodges work.

The building sits just outside Edmonton’s downtown in a former RCMP compound that was handed over to CSC in 1975. A stern, paramilitary pedigree is baked into the building’s Gothic Revival façade, but there’s little else to suggest it’s part of the prison system.

A bowl of ceremonial sage smoulders just inside the unlocked front door. Staff and residents scurry in and out of a central reception office, none pausing to query two unannounced visitors. Most daycares have more security.

Staff and residents address one another by first name as they banter, tease and make plans for a coming sun dance on nearby Alexander First Nation.

The lodge was one of a trio of Indigenous-run healing lodges opened in the late 1990s, and its success seemed to open the way for a massive expansion around the turn of the century, according to CSC documents.

One 2001 report states CSC was in the process of signing two Section 81 agreements, with another 20 in the works. It boasts of a 6-per-cent recidivism rate for healing lodges, compared with a national rate of 11 per cent for all offenders in CSC custody.

To assist the expansion, the Chrétien government set aside $12-million to develop new healing lodges. The program earned international attention, with features in major U.S. newspapers and a research article by Northern Arizona University criminology professor Marianne O. Nielsen, who concluded that CSC seemed ready to turn over the majority of its Indigenous inmates to Indigenous-run healing lodges. She found that the recidivism rate at Stan Daniels was just 3.5 per cent, compared with 23 per cent federally, and suggested the model could work well in the United States, too.

An officer at a B.C. prison wears a Correctional Service Canada patch.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

But at some point in the early 2000s, without fanfare, CSC abandoned its push. The $12-million from Ottawa was “refocused” to pay for Indigenous programs in prisons rather than build new lodges, according to a 2006 CSC strategic plan. The service explained that “several failed attempts” to establish new healing lodges, along with an internal study that found recidivism was actually higher (19 per cent) for people released from healing lodges than for Indigenous people released from other minimum-security prisons (13 per cent), persuaded the agency to double-down on prisons rather than lodges. Several subsequent CSC studies have reached different conclusions. One, completed this year, showed that healing lodges tend to accept higher-risk residents who have recidivism rates comparable to lower-risk prisoners released from other minimum-security institutions.

“To my mind, money was taken from communities and internalized into CSC’s operations,” said Mr. Buller, former director of aboriginal corrections policy for Public Safety Canada, who would author a 2012 report for the Correctional Investigator on CSC’s Indigenous policies.

The Trudeau government has expressed ambitions to expand the Section 81 network. In successive mandate letters, the Minister of Public Safety directed the CSC commissioner to strike more Section 81 agreements. But since the Trudeau government came to power in 2015, just one new lodge has been established, Eagle Women’s Lodge in Winnipeg.

Marty Maltby, acting director-general of CSC’s Indigenous Initiatives Directorate, said several communities have expressed interest in having a healing lodge in recent years, but talks have broken down for two main reasons. Often communities have an all-encompassing notion of a healing lodge that would operate as women’s shelter, addictions centre, counselling office, transitional housing and more.

“When you’re talking about all these other populations,” Mr. Maltby said, “the opportunity to have serving offenders and those vulnerable groups in the same house may not always work.”

In other cases, the interested First Nations community is simply too remote. “We want to be able to provide the best opportunities for individuals going back to communities,” Mr. Maltby said. “And you know, when those locations are so far removed from the cities, the towns, the places they want to go, it doesn’t really make sense.”

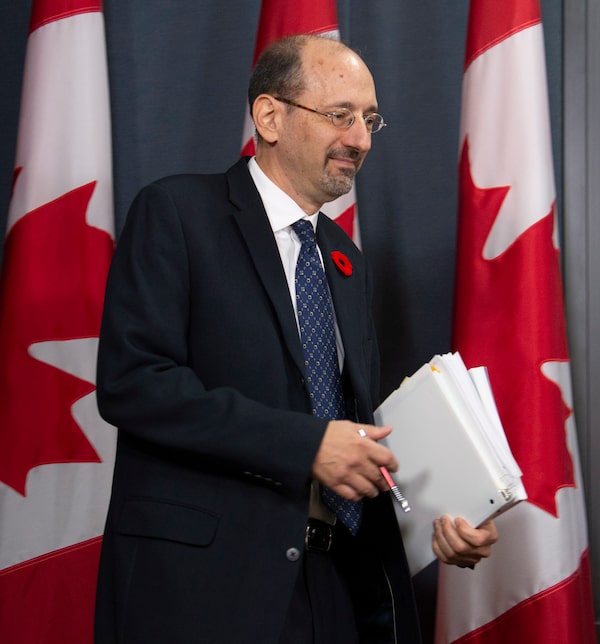

Ivan Zinger, shown in 2018, is Canada’s Correctional Investigator.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

The few Indigenous-run lodges that do exist survive on precarious budgets. In April, Canada’s Correctional Investigator, Ivan Zinger, toured Stan Daniels and came away struck by its scarcity. There were just 37 residents (they don’t call them inmates at Stan Daniels) occupying the building’s 73 beds. The facility lost money unless it filled at least 56 beds owing to CSC’s per diem funding arrangement, according to then-director Dan Jones.

Across Canada’s 10 healing lodges, the occupancy rate was 78 per cent before the pandemic and plummeted to 51 per cent over the past two years, according to figures obtained through Access to Information legislation. While the CSC attributes much of that drop to COVID-19 measures throughout its institutions and to a broader 11.7-per-cent decline in the prison population since Mar. 1, 2020, the Correctional Investigator’s office had already flagged the issue in years prior.

Dr. Zinger saw evidence of funding shortages everywhere at Stan Daniels. Bedsheets, shower curtains and other makeshift dividers separated the beds. Mr. Jones, a former Edmonton police officer, told Dr. Zinger that his staff earned half as much pay compared with employees at comparable facilities run by CSC, where correctional officers make anywhere between $25 and $45 an hour.

“There is no money for anything, even for welcoming packages for new residents who do not have soap, shampoo, deodorant, tooth brushes, etc.” wrote Dr. Zinger in an e-mail to his staff, obtained through Access to Information legislation. “The [executive director] is recruiting free volunteers to lead yoga classes, attend beehives on the roof, literacy support, etc.”

Primary worker Darron Legge and finance co-ordinator Twila Turcotte staff the front desk at Stan Daniels.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

Despite the challenges, Dr. Zinger, who’s held the Correctional Investigator position for five years, reported that Stan Daniels staff were doing a terrific job. “The relationship between residents and staff are some of the best I have witnessed,” he wrote.

As he toured the halls, Dr. Zinger remembered that he’d visited the facility once before, in 1998, when he was a human-rights researcher and the healing lodge concept was being launched. The building was a little shabby, but he came away impressed with the progressive vision. “There was great hope then that the correctional system was starting to better respond to the unique needs of Indigenous people,” he recalled.

Since those hopeful early days, progress had stalled. Dr. Zinger was surprised to find that Stan Daniels looked the same as it had in 1998, only half as full. And while the original vision was for Indigenous-run healing lodges to open up across the country, none of the existing six are located in B.C., Ontario, the Atlantic provinces or the northern territories.

To Dr. Zinger, that neglect didn’t make sense. The Section 81 healing lodges worked. Study after study, including some conducted by the CSC, had shown that offenders released from healing lodges were less likely to return to a criminal life than those released from traditional penitentiaries. One Auditor-General’s report in 2016 found that Indigenous offenders released from healing lodges were far more likely to comply with their parole (78 per cent) than those released from minimum-security institutions (63 per cent).

Recidivism aside, there’s a legal obligation. The part of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act directing CSC to create correctional policies, programs and practices that respond to the needs of Indigenous peoples is considered an extension of Section 35 of the Constitution Act recognizing distinct Indigenous rights.

Dr. Zinger had spent much of his tenure as Correctional Investigator pressing the CSC to address the overrepresentation issue by fulfilling the CCRA’s promise – expanding its roster of Indigenous-run healing lodges and bringing their funding in line with government-run institutions. His predecessor, Howard Sapers, had come to the same conclusion, as had the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and two parliamentary studies on Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system.

As Dr. Zinger left Stan Daniels Healing Centre, however, he realized all that advocacy, all that political capital, had come to naught.

“With so few beds available at healing lodges and in light of the federal government’s priorities, it is deplorable that the occupancy rate is so low,” he said.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LJEPMKMOPFAS3KAGOGPX3ERCBM.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/2MYYJV37G5FOJLNEHUENRTFOO4.JPG)

A few blocks away from Stan Daniels, at Buffalo Sage Wellness House, a 28-bed healing lodge for women, identical problems exist. Operated by Native Counselling Services of Alberta, the same non-profit organization that runs Stan Daniels, Buffalo Sage looks like any low-rise residential complex from the outside. But inside, it’s a warren of narrow hallways and low ceilings. Everything feels cramped, including the central ceremony room, where six people make a crowd.

They could use a new building and better salaries. A parole supervisor, Elaina Myles, said she could earn an extra $30,000 by taking a job with CSC. The lodge, she said, routinely spends around $34,000 on training a new staff member to CSC standards only to see that person leave for higher-paid government work.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m a training camp for CSC,” Ms. Myles said. “A lot of my staff have gone over there, and good for them. What we do here is a lot of work because we don’t have the same resources.”

In early May, The Globe reported that fully half of all women in federal penitentiaries were Indigenous, a state of affairs Dr. Zinger called “shocking and shameful.” At Buffalo Sage, the reaction was more subdued. Women said the figure seemed low compared with the scenes they’d witnessed at various prisons in CSC’s Prairie region, where they found programs lacking and security rigid.

“You’re just a number or a last name in prison,” said Gaylen Anderson, bouncing her two-month-old boy, Lincoln, on her knee. “Here, they get to know who you are.”

Residents credit the facility’s Spirit of a Warrior program, which addresses anger linked to historical trauma, for helping them understand the origins of any violent tendencies they may have. Depending on the day, they take part in sharing circles, powwows, round dances and sun dances.

Funding arrangements differ for every healing lodge, but, in general, the lodges bill CSC for in-custody offenders based on approved rates. In 2009-10, the agency allocated $21,555,037 to CSC-run lodges and just $4,819,479 to Section 81 facilities. In 2012, the Correctional Investigator found that the cost of every resident at CSC-controlled healing lodges is $113,450, compared with just $70,845 at Indigenous-run facilities. Across all CSC prisons, the average cost per prisoner is about $115,000.

“To ask Indigenous communities and groups to get involved in community corrections and healing lodges and ask them to do it at a discount rate is just not right,” Dr. Zinger said.

Buffalo Sage residents - including Ms. Anderson, second from right - gather in the building's spiritual room to share their experiences in the criminal justice system.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

COVID-19 stretched their finances even more. Only minimum-security prisoners, and select medium-security prisoners, can apply for residence at a healing lodge. Those lower-risk designations require prisoners to complete an array of programs and risk assessment tests.

With most prisons locked down to prevent virus transmission, programming came to a halt, and the normal movement of prisoners from maximum to medium to minimum security happened at a much slower pace, starving healing lodges for new residents.

The restrictions also prevented outreach workers from visiting prisons to meet and recruit potential healing lodge residents.

“If you don’t have access to inmates, you can’t tell them what a healing lodge is and how to apply,” said Marlene Orr, executive director for Native Counselling Services of Alberta.

For its part, CSC established a new funding formula during the pandemic to ensure Section 81 lodges remained solvent when bed occupancy dropped.

As for funding inequities, Mr. Maltby, the CSC Indigenous initiatives director, said that the lodges generally renegotiate with CSC every five years and that all negotiations are “open, transparent and equally balanced.”

Their funding might compare poorly to other CSC institutions, he said, because healing lodges operate more like halfway houses than prisons. Many lodge residents are on day parole and don’t require the same level of expensive programming and supervision as prison inmates.

But while the new funding formula threw Section 81 lodges a lifeline during the worst of the pandemic, Dr. Zinger would rather build them a boat.

Canada already has one of the best-funded correctional systems in the world, with a staff-to-prisoner ratio of around 1.2:1.

Dr. Zinger proposes closing a handful of conventional penitentiaries – where there are currently 4,000 empty cells due to declines in the non-Indigenous prison population – and reinvesting the savings in serving the Indigenous prison population, which grew from 3,500 people in 2016 to 4,100 by 2020.

“Healing lodges need to be vastly increased in number,” he said. “And CSC needs to reallocate a significant portion of its budget to fund those sorts of initiatives.”

CSC has ignored the recommendation to refocus its entire budget, but it has acknowledged a need to meet with more communities interested in healing lodges. Mr. Maltby said the pandemic halted many of those community conversations and that the CSC is currently assessing how many healing lodges it needs.

Mr. Johnson appreciates being able to connect with his Cree heritage at Stan Daniels.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

For now, Stan Daniels and other healing lodges continue writing success stories.

“I came here at age 25, but I was really still 15,” Mr. Johnson explains. “I’d just done 10 years straight. Prison stunts your growth. People think you go to prison to rehabilitate. I mean, I guess anything’s possible. But that doesn’t happen. You’re in survival mode every day.”

Even after moving to Stan Daniels, he still wasn’t a model resident, once disappearing from the lodge for months while police looked for him.

But on May 25, Mr. Johnson earned day parole, which means he can leave Stan Daniels each day as long as he returns at night. He acknowledges some nervousness about re-entering a world, and a work force, with which he has little experience. He’s earned day parole at least three times before only to return for violating conditions, including using marijuana.

These days, he’s working a construction job for $26 an hour, but he’s got greater ambitions. He says he’s close to securing a job with Y:Five-0, an Edmonton police unit that works with the city’s 50 most prolific young offenders to divert them away from a criminal lifestyle. “I have the street cred to do the job,” he said. “I’ve been through the worst of the system and I want to open their eyes. I want to make a difference.”

He remains ashamed of his crime and wants to elevate the name of his victim wherever possible. “I want his name to shine through,” he said. He’s open to public speaking, but he prefers verse. During a session in the Stan Daniels gym, he finishes some bicep curls and bursts into rhyme:

What’s gangsta? Is it really doing time in the pen? Cuz anyone can go to prison at any given time, my friend. Wanna know what gangsta is? It’s taking care of you kids. Gangtas go back to school, go to work and open up a biz. Gangstas go buy a house for their mother. Gangstas keep their friends out of prison, now that’s a real brother.

After a life inside, he wants to keep others out – and he thinks healing lodges could be the key. “I still make mistakes,” he said, “and Stan Daniels has consistently brought me back and given me the opportunity to grow. For that, I’ll always be grateful.”

Mr. Johnson performs some of his rhymes at Stan Daniels.Jason Franson/The Globe and Mail

Race and justice in Canada: More from The Globe and Mail

The Decibel

There are only 10 healing lodges in Canada. What happened to politicians’ promises to build more? Patrick White explains. Subscribe for more episodes.

Bias Behind Bars: A Globe investigation

Auditor-General says corrections authorities not preventing systemic racism in federal prisons

How The Globe uncovered systemic bias in prisoners’ risk assessments

For Indigenous women in prison, bias leaves many worse off than men

Commentary

Ryan Beardy: Home is at the heart of the Indigenous prison crisis

David Neufeld: Canada must commit to better rehabilitation for federal offenders

Akwasi Owusu-Bempah and Alex Luscombe: We can’t reach racial equality without drug law reform