122,456

Total number of inactive wells in western Canada

Nearly three-quarters of the dormant wells are in Alberta, the country’s largest energy producer. Saskatchewan has 25,857 idle wells and B.C. has 7,382.

The oldest inactive well in Alberta dates back to the First World War. Even though not a molecule of natural gas has flowed from this hole for a century, it remains on the landscape, along with another 122,455 idle wells in the province and in Saskatchewan and British Columbia. Almost 72,000 of those wells have not produced any oil or gas for more than five years; 9,079 have been dormant for more than two decades.

The number of inactive wells in Western Canada has surged in recent years. A Globe and Mail analysis of data from the three provinces shows there are 54,147 more inactive wells today than in 2005.

That rising inventory is a concern for energy regulators, landowners, the petroleum industry and the public.

While many American states have rules determining how long companies can keep wells idle before they must either put them back into production or permanently seal them, none of the three western provinces legislate cleanup timelines. This means companies can put off remediation work indefinitely.

Alternatively, they can transfer their junk wells to thinly capitalized firms. The problem is that when these companies fail, as they increasingly have since the downturn in the oil patch, the environmental responsibility for those wells is dumped onto provincial regulators and so-called industry orphan-well funds.

Wells that aren’t properly plugged and sealed pose dangers to the environment and people. They can leak methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere and contaminate soil and water with hydrocarbons and brine, affecting future development.

“The whole underlying principle that we have in Saskatchewan is that industry pays for cleanup,” said provincial auditor Judy Ferguson, who released a report this summer on environmental and financial liabilities in the oil patch. “It’s important that the [energy] ministry do everything that it can do to make sure that it is enforcing and designing its programs so that producers pay for cleanup.”

The Saskatchewan government has been reviewing its policies for dealing with inactive wells but has not yet established criteria for their abandonment. Regulators in Alberta and B.C. are also examining the issue.

Petroleum geologist David Speirs worries that an environmental crisis is looming.

“It’s a disaster waiting to happen,” said Mr. Speirs, founder of the Freehold Owners Association, a volunteer organization of landowners with mineral rights on their properties. “Everybody’s sort of pushing it down the road hoping prices are going to come back for natural gas, but at some point, if they don’t, then we as the citizens are going to have one humongous liability.”

Cumulative number of inactive wells

140,000

2018

Sask.

25,857

120,000

In 2005,

Saskatchewan

had 16,010

inactive wells

100,000

B.C.

7,382

80,000

60,000

Alta.

89,217

40,000

20,000

0

1999

2003

2007

2011

2015

Note: Saskatchewan only provided data for 2005 and 2018.

Cumulative number of inactive wells

140,000

2018

Sask.

25,857

120,000

In 2005,

Saskatchewan

had 16,010

inactive wells

100,000

B.C.

7,382

80,000

60,000

Alta.

89,217

40,000

20,000

0

1999

2003

2007

2011

2015

Note: Saskatchewan only provided data for 2005 and 2018.

Cumulative number of inactive wells

140,000

2018

Sask.

25,857

120,000

In 2005,

Saskatchewan

had 16,010

inactive wells

100,000

B.C.

7,382

80,000

60,000

Alta.

89,217

40,000

20,000

0

1999

2003

2007

2011

2015

Note: Saskatchewan only provided data for 2005 and 2018.

To understand the lifespan of a well requires delving into a world of industry terminology. Active wells produce oil or gas – sometimes both. Inactive wells have stopped pumping, often because the economics don’t justify production. But these wells haven’t been filled with cement or had the system that provides pressure control, known as the wellhead, removed. That stage is called “abandoned” or “plugged.”

After plugging, a well site is supposed to be reclaimed and returned to its original state.

The last two steps can be costly, roughly $100,000 per well, according to an analysis by the C.D. Howe Institute. As profits have dwindled, many producers have been reluctant to pay those costs.

The percentage of inactive wells held by a single company can be a sign of trouble, as a 2017 Saskatchewan government analysis obtained by The Globe through a freedom of information (FOI) request shows. In examining 31 energy companies that had failed, the province found that, on average, inactive wells made up 60 per cent of their total well counts, compared with 40 per cent for solvent companies. Increased inactive well counts also raised the likelihood that a company would bail on the security deposits it owed the government – money used for cleanup when an operator goes under.

These two factors, combined with the ability of bankruptcy trustees to disclaim distressed assets such as inactive wells, clearly underscore that the “percentage of inactive wells must be a consideration in liability management programs,” concludes a draft government report, also obtained under FOI legislation.

To address flaws in its liability-rating program, known as LLR, the Saskatchewan government has proposed a new system for evaluating the movement of wells that would take into account how many inactive assets are being traded and what that would mean for the new owner’s balance sheet.

“Given the new reality in the oil and gas industry, [the ministry] is of the opinion that it is imperative to replace the LLR program for transfer process in order to better protect the industry, and ultimately to protect taxpayers from unfunded liabilities,” the draft government report concludes.

One year after the proposed changes were presented to the oil and gas industry, the government’s new model remains in a “testing phase,” said a spokesperson for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Energy and Resources. In some instances, higher security deposits are being collected.

Brad Herald, vice-president of Western Canada operations for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, said the industry organization recognizes that there is a need to increase scrutiny of well transfers and inactive inventories.

“Through the downturn, we saw some significant [company] failures,” he said. “As we look at the licensee liability rating, it had failed to pick up some of the risks, and we said: How would you augment that system?”

Some American states force companies to seek ongoing approvals and post security bonds to keep wells inactive. Pennsylvania, for example, only allows operators to hold onto an idle well if they can show it is in good mechanical shape and that there is a reasonable chance production will restart. After five years of inactivity, the operator must seek yearly approval to keep the well dormant.

In Texas, the largest oil and gas producer in the United States, operators can keep a well idle for only one year. After that, they must apply annually for extensions that demand security bonds. In many cases, companies must also provide a report from an engineer or geoscientist that certifies the inactive well could be brought back online.

The rules are designed to dissuade companies from delaying their environmental obligations and to thwart the dumping of unproductive wells – and their liabilities – onto operators that are in danger of going bankrupt.

In Canada, governments have so far been reluctant to impose stringent regulations. Saskatchewan is studying time limits and other measures to deal with the glut of inactive infrastructure. Similar proposals are now being floated in Alberta, where the regulator has recently encouraged companies to partner on cleanup to reduce costs and speed up reclamation.

For a brief time in the late 1990s, Alberta’s regulator had a five-year limit on inactive wells. When that clock ended, producers had to either abandon a well, reactivate it or pay a security deposit to keep it idle. That time limit was lifted in part due to industry pressure.

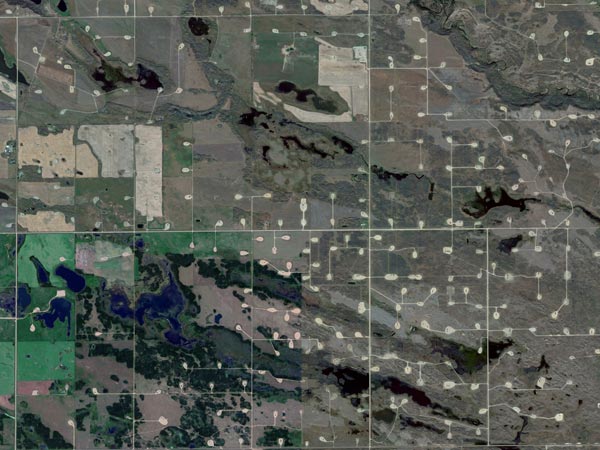

A deeper look at Western Canada’s inactive wells

Canada’s inactive wells have piled up over decades, spanning wide swaths of the West as companies big and small have put off cleanup costs after cashing in during the boom.

Fort St. John is ground zero for a hoped-for liquefied natural gas boom in British Columbia. But an older era’s operations have struggled because of a supply glut and low prices.

Canadian Natural Resources is among the country’s biggest oil and gas producers. Its oldest inactive well has been shut off since Feb. 29, 1928, yet the well site has not been remediated.

The oldest inactive well in Alberta has been idle since June 30, 1918.

The Bakken shale patch was a boon for Saskatchewan until oil prices crashed in 2014. The oil here is extracted through a process called fracking, which involves injecting fluids deep underground to shatter rock and release the trapped oil.

The Lloydminster region, which straddles Alberta and Saskatchewan, is known for its heavy oil deposits. A drop in prices, along with a chronic price gap between Western heavy crude and the North American benchmark, West Texas Intermediate, has curtailed development.

Sources: Data for all visualizations in this series are sourced from the Alberta Energy Regulator, the BC Oil and Gas Commission, Saskatchewan's Ministry of Energy and Resources, the Provincial Auditor of Saskatchewan and the Orphan Well Association.