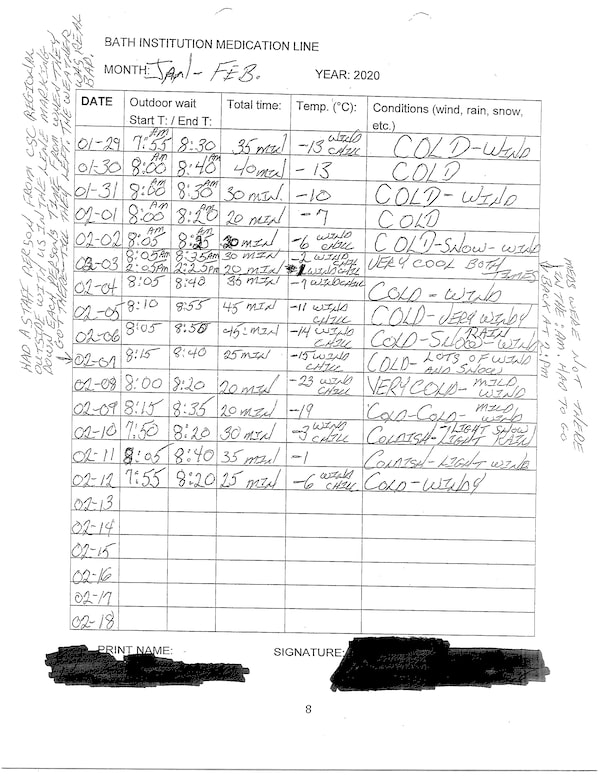

A prisoner at Bath Institution, who lives with a severe form of lupus, keeps track of the time he spends waiting outside for his medications. This document was shared directly with The Globe by Paul Quick, with the Queen's Prison Law Clinic.Supplied

One morning each week, a man pushes Ross Evans in a wheelchair to a lineup outside of the health services building at Bath Institution, a medium-security prison 25 kilometres west of Kingston.

No matter the weather, he regularly waits about 40 minutes to receive the prescription pills he takes daily to manage his diabetes, heart problems and several other health conditions. In the past year, he has waited in freezing rain and even a blizzard, wearing a thin polyester jacket and sneakers.

“I don’t think you would ever see a hospital or pharmacy treating patients this way in the community,” Mr. Evans, 56, said in a legal statement in early March. “But us, they treat us how they please. It’s like we are not even human beings to [the correctional service].” Mr. Evans is serving an indeterminate sentence for an offence involving violence.

Mr. Evans is among a group of inmates at Bath who are supporting a human-rights complaint against the Correctional Service of Canada lodged by the Queen’s Prison Law Clinic. Submitted this week to the Canadian Human Rights Commission, the complaint argues that the outdoors medication lineup discriminates against prisoners who are disabled or older. Bath has a disproportionately high number of older prisoners.

The spread of novel coronavirus in Canada is heightening prisoners’ concerns, said Paul Quick, a staff lawyer representing the legal clinic.

Mr. Quick suggested that, in light of the pandemic, health care staff could deliver prisoners’ medications directly to their living units, as staff do at Millhaven Institution, a maximum-security facility nearby. Of the several dozen facilities that the correctional service manages, at least two others, in addition to Bath, require inmates to line up outdoors for medication. One of the lineups has a covering.

The Bath complaint requests three remedies: that the correctional service build a permanent, indoor waiting area; that it construct a heated, outdoor shelter with seating in the interim; and that it provide financial compensation for patients who were required to wait outside.

Christina Tricomi, a spokesperson for the correctional service, declined to answer questions about the complaint or the lineup generally, saying Wednesday that the service was unable to confirm the complaint had been filed with the commission. (Mr. Quick submitted the complaint by e-mail early Monday morning and sent a copy to the service several minutes later, according to e-mails shared with The Globe).

In legal statements provided to The Globe, five prisoners described waiting times between 15 and 45 minutes, and up to an hour at the longest. While some men, such as Mr. Evans, are allowed to pick up a multiday supply of medication at one time, others are required to wait in line once or twice each day.

One man living with HIV described his fears of getting sick because of his exposure to the elements with a weakened immune system. Two men said they occasionally skipped picking up their medications, including one man living with severe lupus who was told that a strict medication regime could help slow the progression of organ damage.

The human-rights complaint is not the first time the correctional service is hearing concerns about the lineup. Between early 2018 and 2019, one incarcerated patient submitted five grievances, suggesting ways to improve the system. His name was redacted from documents provided to The Globe.

In response to one of his grievances, the institution’s then-warden explained in February 2018, that construction was “currently” under way in the health-care building to provide a waiting room for patients. In the interim, she said she had asked staff to purchase an outdoor shelter.

In response to another grievance by the same prisoner, Ryan Beattie, the institution’s current warden, wrote that waiting times are typically less than 12 minutes, a statement contradicted by prisoners’ accounts. In early 2019, the prisoner submitted his final grievance, this time to the correctional service’s national headquarters. About eight months later, in September, he received a response. An adviser told him that the completion of an outdoor shelter was anticipated that fall – before winter weather hit.

In their statements, two prisoners pointed out that the service had recently begun digging near the area of the lineup, and while they suspected it could be for an outdoor shelter, one has yet to materialize.

In the fall of 2018, the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI), an ombudsman for federal prisoners, also raised concerns with Bath’s leadership. In response, the warden shared a proposal for an outdoor “awning/shelter” that had been submitted to procurement services, according to a briefing note obtained through a public records request.

But Ivan Zinger, the correctional investigator of Canada, said an outdoor shelter isn’t an adequate solution.

“A shelter or an awning is still going to have people, especially in the winter, waiting outside. So it’s a half measure and even that half measure wasn’t dealt with,” Mr. Zinger said in an interview.

Though federal prisoners have a legal right to essential health care at professionally accepted standards, the most common type of complaint cited by prisoners to the OCI was related to health care last year, its annual report notes.

In the Bath lineup for medication, there are no benches or chairs to sit on, nor any shade or shelter, said a 61-year-old patient living with a severe form of lupus. In the winter, a plastic salt bin left near the building’s entrance forms a makeshift seat for two patients – usually whoever appears to be suffering most, he added. His name was redacted from the documents provided to The Globe.

This past winter, the man said he left the lineup without his medication four or five times when the weather was especially bad. On those types of days, the correctional officers supervising them would do so from inside vehicles, he said.

The number of federal prisoners who are 50 and older has been on the rise for at least a decade, partly because of the widening of mandatory minimums since 2005 and the growth of people being sentenced later in life. In a 2019 joint report on aging and dying prisoners, the OCI and Canadian Human Rights Commission found that some older inmates are being “warehoused” in prison long past their parole eligibility dates, even as they face terminal illnesses.

Bath’s medication line is a symptom of a much larger issue, said Mr. Zinger, who said many older inmates could be managed more appropriately – and far less expensively – in community settings.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.