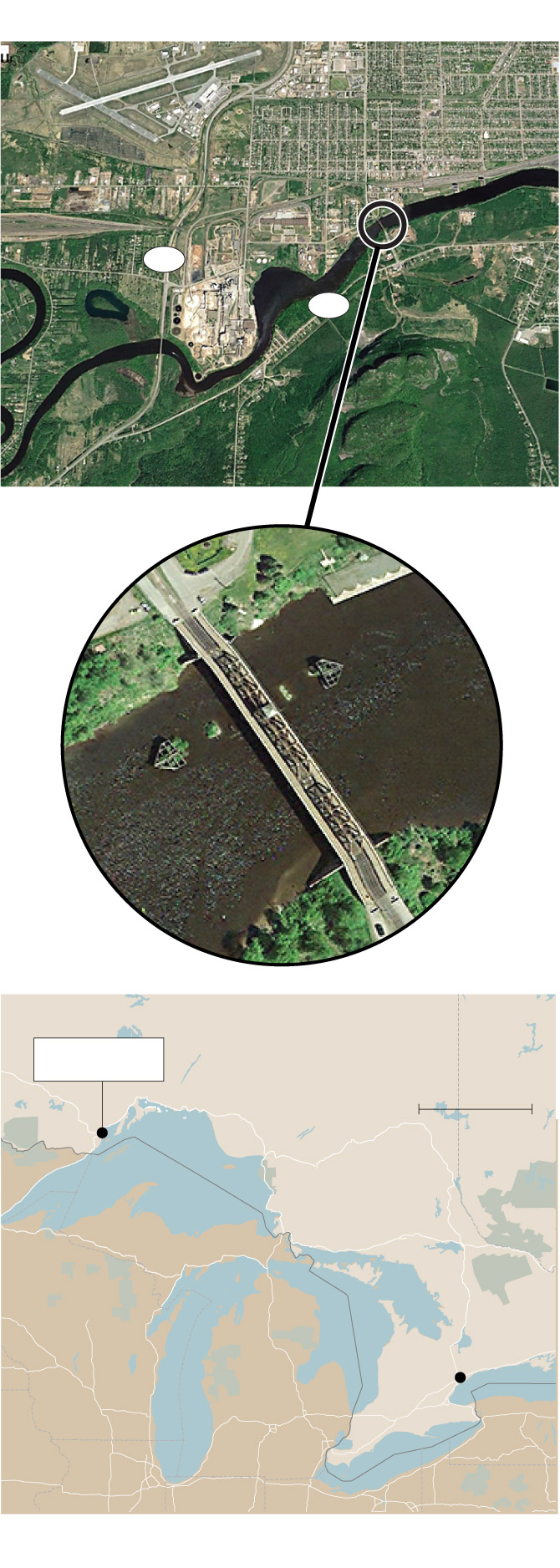

In 1909, the James Street Swing Bridge, seen here, was completed, connecting the former city of Fort William, now referred to as Westfort in Thunder Bay's south end, to the Fort William First Nation.David Jackson/The Globe and Mail

People watched from their windows as thick black smoke reached high above the silver birch trees along City Road on the night the bridge caught fire.

A blaze that size, on a structure that important, couldn’t help but draw attention.

For more than a hundred years, the James Street Swing Bridge had been a key link between the city of Thunder Bay and neighbouring Fort William First Nation − two communities set apart physically by the broad Kaministiquia River but equally by heritage and history.

“It was sort of our bridge to becoming friends and community members with each other,” said Walter Bannon, who owns a gas station on the reserve. “For the community itself, it has been a lifeline.”

On the evening of Oct. 29, 2013, the sight of that lifeline becoming a barrier brought out dark speculation. Some in town suggested that residents of the reserve had set the fire, to get a new bridge built; others on the reserve wondered if city-dwellers had lit the match, to keep their Indigenous neighbours out.

JAMES STREET BRIDGE

JAMES ST.

THUNDER BAY

Thunder Bay

International

Airport

61

61b

FORT WILLIAM

FIRST NATION

ONTARIO

Thunder Bay

0

250

KM

WISCONSIN

Toronto

MICHIGAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

IMAGES: GOOGLE EARTH

JAMES STREET BRIDGE

JAMES ST.

THUNDER BAY

Thunder Bay

International

Airport

61

61b

FORT WILLIAM

FIRST NATION

ONTARIO

Thunder Bay

0

250

KM

WISCONSIN

Toronto

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

MICHIGAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

IMAGES: GOOGLE EARTH

JAMES STREET BRIDGE

JAMES ST.

THUNDER BAY

Thunder Bay

International

Airport

61

61b

FORT WILLIAM

FIRST NATION

ONTARIO

Thunder Bay

0

250

KM

WISCONSIN

Toronto

MICHIGAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL; IMAGES: GOOGLE EARTH

The fire department would offer their own explanation for the power of the flames: Over the years, the train tracks had been treated with the highly flammable wood preservative creosote. But dry official pronouncements hardly eased suspicions, or the burden of what came next.

Although the bridge was left standing the following day, with little structural damage beneath the char marks, a legal standoff between Canadian National Railway and the city over who had responsibility for repairs ensured that the bridge would stay closed to drivers for nearly six years − as it remains to this day.

Last month, the Supreme Court dismissed CN’s final legal appeal, meaning the responsibility to fix the bridge now firmly belongs to the company. Cars and trucks should be plying the span within months.

In the meantime, the closing has diverted traffic to a dangerous highway, slowed emergency response times, and hurt businesses on both sides of the river. It has also opened old wounds in a racially divided city − and suggested new ways of healing them.

As staggering hate-crime statistics and a pair of official reports on systemic bias in policing focus attention on race relations in this small industrial city halfway across the country, a shuttered bridge has offered a glimpse at how deep divisions run here, and how they might be forded.

In Fort William First Nation, band uses election to press forward despite echoes of colonial past

Hate and hope in Thunder Bay: A city grapples with racism against Indigenous people

The Globe in Thunder Bay: Why we’re here

The James Street bridge is a relic, and carries as much history in its ties as creosote. When the last spike was nailed in 1909, it secured the fate of two communities for a century and more.

The bridge was built as part of an agreement between the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and what was then the Town of Fort William to connect the company’s new transcontinental railway with the Lake Superior port. From there, Prairie grain could be shipped to points south. The town agreed to pay $50,000 toward building a rail bridge across the Kaministiquia if the company agreed to maintain the span for other types of traffic “in perpetuity.”

The deal was a win-win for a mammoth corporation and a booming city. But it was a losing proposition for the First Nation. A related agreement, signed in 1905, forced the band to give up about 650 hectares of reserve land for Grand Trunk to build a railway terminus. That required the community to evacuate its village, abandon thriving farms and dig up graves. Now, for access to the city, First Nation members would depend on the James Street bridge.

Despite the inequities of its construction, the span became an integral part of both communities. Generations of city folk crossed its narrow traffic lanes to the reserve and back. They came to work at the Coastal steel plant or picnic at Chippewa Park. They came for pickerel dinners at Bannon’s restaurant or Triple-A hockey games at the arena. And yes, they came for cheap cigarettes and gas.

After the bridge burned in 2013, many residents of Thunder Bay began walking over the bridge to attend work or to purchase cigarettes at a reduced price.David Jackson/The Globe and Mail

The bridge held even more significance for people who lived on the reserve. It was a kind of private playground for generations of children from the First Nation who grew up flitting between its trusses and dangling from its tracks. More important, all of the banks and hospitals and grocery stores their parents needed were on the other side.

“That bridge is part of people’s identity,” said Damien Lee, a member of Fort William First Nation and a professor of sociology at Toronto’s Ryerson University. “People grew up crossing that bridge every single day.”

If the bridge was a source of connection, it also, inevitably, marked the boundary between two very different worlds − a psychic distance that emerged on the night of the fire. As the flames roared, social media lit up with hate.

“With the res bridge on fire, we just need to find a way to block off the other entrances,” wrote one user.

Another said, “That fire on the bridge could just keep travelling toward the rest of the reserve.”

Mr. Lee knew racism existed in Thunder Bay and had witnessed it firsthand many times. But the reaction to the fire hit him with the force of revelation. “You opened Facebook and the story is that some in Thunder Bay are ready to kick my community while it was down,” he said.

Some local Indigenous people found that the venom lingered, long after the flames had been doused. Sandi Boucher, an author and member of Seine River First Nation who lives in Thunder Bay, said the bridge fire was a turning point for race relations here.

“We noticed a huge shift − and it sounds like something out of a bad movie − but when the bridge burned,” she said, “suddenly the racism got blatant.”

The bridge was a source of connection but also, inevitably, the boundary between two very different worlds − a psychic distance that emerged on the night of the fire filled with hate.David Jackson/The Globe and Mail

Many white residents of Thunder Bay agree that racism in the city has gotten worse in the period roughly coinciding with the closing of the bridge, although there’s little consensus about the cause.

Karen Tretter, who owns an accounting business in Thunder Bay, recalled a recent hair appointment in the city when an Indigenous woman was standing outside and asking for an ambulance. The hairdressers refused to call one until the woman collapsed. “I got my hair completely done by the time she was put in the ambulance,” Ms. Tretter said. “They’re treated like second-class citizens. The bridge is a part of it, but it’s a small part of it.”

Other problems were unleashed by the fire, as well. The closing of the bridge threw up all kinds of hazards for the people who commuted back and forth between the two communities.

Within a week of the blaze, CN had reopened the bridge to rail traffic, but the company said that the structure’s roadways were unsafe. The logic of permitting freight trains to cross, but not Toyota Camrys, escaped many in Thunder Bay, and would in time be unpicked by Canada’s higher courts. But for a time, the city was stuck with it.

With the bridge as good as closed − Thunder Bay is not a walkable city − only one route remained between town and reserve. It took drivers on a fifteen-minute detour from some parts of the city, along the busy Highway 61, whose steady stream of logging trucks and abrupt merging and exit lanes can be treacherous.

Many in the First Nation blame the closing of the bridge for a rash of accidents on Highway 61, which has been forced to accommodate the almost 9,000 vehicles that went across the James Street Bridge daily at last count.

With the bridge as good as closed, only a fifteen-minute detour along the busy Highway 61 connected the two, whose steady stream of logging trucks and abrupt merging and exit lanes can be treacherous.David Jackson/The Globe and Mail

Band councillor Kyle MacLaurin said his sister was in a serious crash on the highway recently. He has little doubt about the safety of the community’s mandatory detour to the city.

“It’s not just an inconvenience,” he said. “It’s a recipe for disaster.”

Slower emergency response times and a resulting uptick in insurance premiums compound the reserve’s anxiety about their newfound isolation. Meanwhile, local businesses have suffered.

“It affected all the businesses from 25 to 40 per cent,” especially in the first year and a half, said Mr. Bannon, the gas station owner. “It hurt.”

Companies in the Thunder Bay neighbourhood of Westfort, adjacent to the bridge, felt a pinch, too.

“It’s affected a lot of Westfort, the traffic flow, everything. It’s hurt us quite a bit,” said Roxanne Dumais, a waitress at the famed local diner, Coney Island Westfort. “It’s almost like Westfort is a ghost town. Things have really declined.”

“The effect was felt right away,” said Earl Wicklund, manager of the grocery store Westfort Foods. “We lost about 10 per cent of our traffic.”

The wide dispersal of economic pain brought on by the bridge’s closing made the problem that much more galling, as two communities entered their sixth year of mutual suffering owing to a legal showdown neither one seemed able to affect.

But it was also possible to detect in that shared frustration a hint of silver lining: Half a decade of being denied easy access to each other had taught both sides that they didn’t like it.

Scott Hamilton, an archeologist at Thunder Bay’s Lakehead University, said that although he was wary of wishful thinking, he thought he saw something hopeful in the episode:

“Two communities, side by side, suddenly realizing − because of that loss of physical connection − how close and connected they really are.”

In the meantime, the lawyers and negotiators got to work. Both chiefs who served during the closing tried to broker deals to reopen or replace the bridge. In 2018, Chief Peter Collins mooted a proposal to install a so-called Bailey bridge on top of the existing structure, at an estimated cost of $8-million, and with a prospective lifespan of 75 years.

But disputes remained about permission and who would pay, moving the case inexorably toward a ruling in the lawsuit between Thunder Bay and CN. Corporate ancestors of both had given birth to the bridge; for it to reopen, one would have to accept custody.

It looked like CN would prevail at first. In June, 2017, Ontario Superior Court Justice Patrick Smith dismissed the city’s application to have the company do the necessary maintenance or structural alterations to get traffic flowing again. The crux of his ruling was that, in 1906, CN had agreed to maintain the bridge perpetually, but only for the type of traffic that was prevalent at the time: that is, streetcars, horses and carts, not cars and trucks.

The city pressed on, though, and a year later, the Ontario Court of Appeal swatted down Justice Smith’s reasoning. “Back in 1906,” wrote Justice John Laskin, “it would not have taken much imagination to realize that in the future, cars and trucks would become a far more common way than horses and carts to get from one place to another.” He overturned Justice Smith’s judgment.

When the Supreme Court declined to hear CN’s appeal in March of this year, the company relented. “Over the past months, CN has sought proposals to reopen the bridge. The successful bidder will be confirmed in the coming days and the work is expected to begin in the spring,” the company wrote in a statement.

The leaders of both communities celebrated.

The Ontario Court of Appeal eventually overturned Justice Smith's judgment, reasoning that 'it would not have taken much imagination' in 1906 to predict that the dominant form of transport in the future would be cars and trucks.David Jackson/The Globe and Mail

“It’s a win for the city and a win for Fort William First Nation,” Thunder Bay Mayor Bill Mauro said.

“Is it a victory? Absolutely,” Chief Peter Collins said. “It’s a victory for me, it’s a victory for the community.”

Some of their constituents responded more tepidly. After all, the Court of Appeal did not maintain that the James Street bridge was a good bridge. Drivers generally had to inch across the ancient structure. In fact, the city of Thunder Bay stopped sending buses over it two years before the fire, in part because the bridge’s narrow traffic lanes and steel plate-lined roadways had been damaging the buses’ sidewalls and tires.

“My hope is that we don’t open this bridge and then forget we need a new bridge,” said Mr. MacLaurin, the band councillor.

The need for a new span over the Kaministiquia can be measured in chewed up tires and scratched paint jobs. But it carries symbolic freight, too. Mr. Lee, the Ryerson professor and band member, said he hopes the community’s shared court victory over CN doesn’t obscure the deep divides that remain in Thunder Bay or the hard work still needed to close them.

“You can’t build bridges on rotten foundations,” he said.