Care team members attend to a South Asian ICU patient after they were turned from a prone position, onto the supine position at Brampton Civic Hospital on May 25, 2021.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The team of six health care workers moved with the speed and precision of a pit crew around a COVID-19 patient lying on his stomach in Brampton Civic Hospital’s intensive-care unit.

A respiratory therapist secured the patient’s breathing tube. Nurses checked the multiple IV lines snaking out of his body. A physiotherapist repositioned the patient’s arms. Wrapping a bed sheet around his body, they counted down and flipped him onto his back.

Staff at this suburban hospital in Brampton, Ont., northwest of Toronto, have become some of the country’s top experts in treating critically ill COVID-19 patients, executing this turning manoeuvre to improve lung function hundreds, if not thousands, of times over the past 16 months.

They’ve also become masters at prepping patients for transfer. Over the course of the pandemic, Brampton Civic transferred out at least 567 infected patients, 150 of them in critical condition, to free up space and staff. That’s more transfers than any other hospital in Ontario.

But the pressure Brampton Civic faced can’t be blamed on the scale of the local COVID-19 epidemic alone. As the only full-service hospital for a city of about 660,000 people, Brampton Civic was full-to-bursting long before anyone had ever heard of COVID-19. The pandemic simply drew attention to the health care funding disparity locals had been living with for years.

“It seems like we can’t ever catch a break,” said Vikram Kapoor, a doctor who grew up in Brampton and now serves as the division head of hospitalist medicine at Brampton Civic. “Because even before COVID, our volumes are high, our ER’s so busy, our beds are underfunded. At least this kind of shines a light on it.”

Many of Brampton’s residents are South Asian, like the man in his 40s who was flipped from the prone to supine position on a morning in late May.

A care team member prepares a prone ICU patient before they were turned over onto the supine position.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Using sheets to help in the task, care team members prepare to turn a prone ICU patient over onto the supine position.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Registered nurse Navdeep Hansra speaks to family members of a South Asian patient in the ICU.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

After the team turned him, nurse Navdeep Hansra spoke by phone, gently in Punjabi, to one of his relatives. “She was crying on the phone,” Ms. Hansra said afterward. “She was very scared.”

When it comes to explaining why Brampton and its neighbouring communities have the fewest hospital beds per capita of any Ontario region, “there’s no reason to beat around the bush,” said Harkirat Singh, a city councillor for northeast Brampton, which includes L6P, the first three characters of the postal code that has had the most per-capita cases of COVID-19 in Ontario since the start of the pandemic. “We are a racialized community and many members cannot speak English as their first language.”

That made it difficult for residents to advocate for themselves as Brampton’s population grew, and as successive provincial governments failed to open enough new hospital beds to keep pace, Mr. Singh said.

“I would argue we were taken advantage of.”

Running out of options

On Jan. 22 of 2020, Brampton council took the extraordinary step of declaring a health care emergency in the city. The motion, moved by Mr. Singh and adopted unanimously, was primarily symbolic, but Mr. Singh felt he had run out of options.

How many more times could he forward complaints about the overcrowded hospital to the local member of provincial Parliament? How could he keep advising constituents who felt they had received subpar care to hire lawyers they could ill-afford? “I just felt like I was powerless,” Mr. Singh said in a recent interview. ”This was something that needed to be done. Obviously, it’s a capacity issue, a funding issue.”

The emergency declaration asked for two things. In the long term, Brampton wanted an additional 850 hospital beds to bring its per-capita share in line with the provincial average. In the short run, it asked for a cash injection to provide the local hospital network with “full staffing and resources in order to provide safe and quality patient care immediately.”

Three days after Brampton declared its health emergency, Canada reported its first case of COVID-19.

“We started the pandemic at 100-per-cent capacity, and that’s been the norm for years in Brampton,” said Mayor Patrick Brown. (Average occupancy at Brampton Civic was actually 108.7 per cent in the eight months leading up to the pandemic. Etobicoke General was worse, with average occupancy of 130.4 per cent in the same period, according to a spokeswoman for the William Osler Health System, which includes both hospitals.)

“There’s one standard of care in older communities like Oakville or Kingston or Kitchener-Waterloo. And there’s another standard in the growing, diverse communities like Brampton, Etobicoke [and] Scarborough,” Mr. Brown said. “It’s unconscionable.”

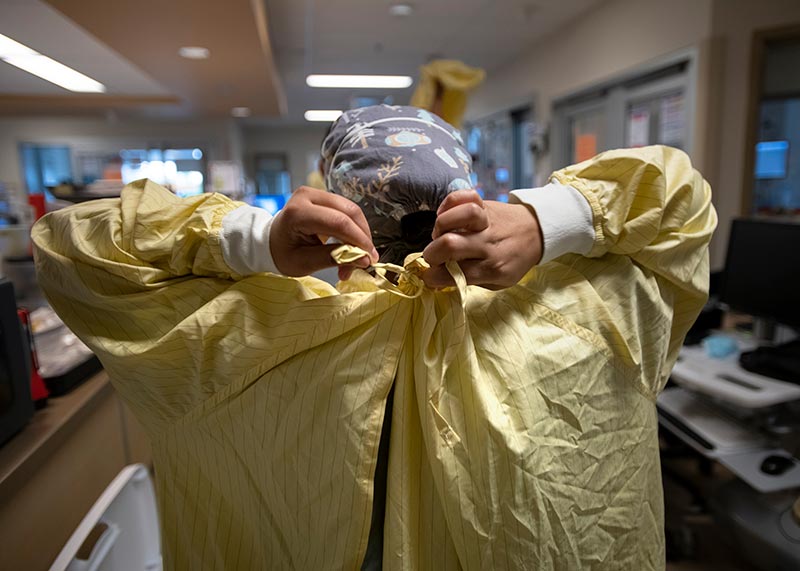

A care team member puts on a gown before turning a prone COVID-19 patient onto the supine position.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Care team members attend to an ICU patient after they were turned from a prone position to a supine position.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Those divergent standards were laid bare in a 2017 briefing note that William Osler’s interim president sent to the head of the Central West Local Health Integration Network (LHIN,) one of Ontario’s old regional health authorities. The provincial NDP obtained the note through an access-to-information request and it made headlines at the time, notably for the revelation that Brampton Civic had treated 4,352 patients in hallways in a single year.

The briefing note showed that in 2015-2016 William Osler had fewer beds and a smaller budget than hospital networks in smaller or similar-sized Ontario cities, despite coping with more emergency-department visits and admitting as many or more patients.

Residents of the old Central West LHIN – which included Brampton and a slice of northwest Etobicoke, and also extended as far north as Shelburne – had 100 hospital beds for every 100,000 residents in 2019-2020. The provincial average was 218.6, according to Ontario Health.

How did the Brampton area wind up at such a disadvantage? The provincial government, controlled by the Liberals from 2003 to 2018 and by the Progressive Conservatives thereafter, wildly underestimated the growing city’s needs.

On top of that, Brampton’s population exploded at a time when the Liberal governments of Dalton McGuinty and Kathleen Wynne were trying to avoid opening expensive new hospital beds, something that contributed to overcrowding in many hospitals. Their aim was to shift as much care as possible out of traditional hospitals and into the community.

Brampton Civic, which was built to accommodate 90,000 emergency department visits a year, blew past that mark less than two years after it opened in 2008. It hit 138,000 ED visits by 2016-2017, despite a third-party review that found residents visited the ED less than expected, based on provincial averages. Much of the increased traffic was comprised of patients sick enough to require admission.

At the same time, the Peel Memorial Centre for Integrated Health and Wellness, a day-surgery and urgent-care centre in Brampton that replaced the old full-service Peel Memorial Hospital, didn’t syphon nearly as many less-seriously-ill patients away from Brampton Civic as forecast.

Opened in February, 2017, with funding for 10,000 visits a year, the urgent-care centre was logging 75,000 annually by 2018-2019, which explains how internal figures, also obtained by the NDP, showed traffic at the urgent-care centre topping 550 per cent of its funded capacity that year.

“When I came to Brampton, there were a lot of individuals [of] European descent,” said Ato Sekyi-Otu, an orthopedic surgeon at Brampton Civic and a member of the Black Physicians’ Association of Ontario. “That demographic has dramatically changed in the last 20 years, as has the funding. So, I mean, there’s a correlation there.”

If Brampton had more hospital beds, its lone hospital would not have been forced to transfer out so many COVID-19 patients. Although Brampton’s case rate was among the highest in the province, its hospitalization and death rates weren’t, according to a Globe and Mail analysis of data from the non-profit Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. (The data exclude cases in long-term care.)

L6P, for example, is first in confirmed infections per capita, but 57th in terms of hospital admissions and tied for 128th in deaths, compared with other forward sortation areas, which are defined by the first three characters of a postal code.

COVID-19 case rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

King

Caledon

Vaughan

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Toronto

Mississauga

Cases per 100

Oakville

0

2

4

6

8

10

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

COVID-19 case rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

King

Uxbridge

Caledon

Pickering

Vaughan

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Halton

Hills

Toronto

Mississauga

Milton

Cases per 100

Oakville

0

2

4

6

8

10

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

COVID-19 case rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

Whitchurch-

Stouffville

King

Uxbridge

Richmond

Hill

Pickering

Vaughan

Caledon

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Halton

Hills

Toronto

Mississauga

Milton

Cases per 100

Oakville

0

2

4

6

8

10

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

Hospitalization rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

King

Caledon

Vaughan

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Toronto

Mississauga

Hospitalizations

per 1,000

Oakville

0

2

4

6

8

10

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

Hospitalization rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

King

Uxbridge

Caledon

Pickering

Vaughan

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Halton

Hills

Toronto

Mississauga

Milton

Hospitalizations per 1,000

Oakville

0

2

4

6

8

10

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

Hospitalization rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

Whitchurch-

Stouffville

King

Uxbridge

Richmond

Hill

Pickering

Vaughan

Caledon

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Halton

Hills

Toronto

Mississauga

Milton

Hospitalizations per 1,000

Oakville

0

2

4

6

8

10

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

Death rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

King

Caledon

Vaughan

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Toronto

Mississauga

Deaths per 1,000

Oakville

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

Death rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

King

Uxbridge

Caledon

Pickering

Vaughan

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Halton

Hills

Toronto

Mississauga

Milton

Deaths per 1,000

Oakville

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

Death rates

As of June 7, 2021

Data suppressed*

Aurora

Whitchurch-

Stouffville

King

Uxbridge

Richmond

Hill

Pickering

Vaughan

Caledon

L6P

Markham

Brampton

Halton

Hills

Toronto

Mississauga

Milton

Deaths per 1,000

Oakville

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

*Rates derived from 5 or fewer counts are suppressed.

In late March, Ontario Premier Doug Ford announced that his government planned to expand the Peel Memorial Centre with a new building, including 250 new beds, and a 24/7 emergency department.

The Premier’s announcement didn’t make clear precisely what types of patients the new beds at Peel Memorial would accommodate or when the addition – which Mr. Ford described as a new hospital – would open.

Alexandra Hilkene, a spokeswoman for Ontario Health Minister Christine Elliott, said in a statement that the current plan is to reserve the new beds for “post-acute inpatient care, including complex continuing care beds and rehabilitation beds,” while studying whether some acute-care beds would be needed to support a future 24/7 emergency department at Peel Memorial. In the meantime, the province has committed up to $18-million in 2021-2022 to run the urgent-care centre around the clock, Ms. Hilkene said.

William Osler spokeswoman Emma Murphy also said that the hospital network has “worked closely” with the Ministry of Health as well as Ontario Health, a provincial agency that oversees the day-to-day operations of the health care system, to address its capacity needs. “In October, 2020, Osler received additional funding to support 87 more beds to help manage COVID-19 and an anticipated winter surge across our inpatient hospitals. These beds have supported Osler’s ability to provide safe and appropriate care to patients since that time,” she said by e-mail.

When Mr. Ford made his announcement at Peel Memorial on March 26, the third wave of COVID-19 was gathering speed. It would soon slam into Brampton Civic, testing the resilience of the doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and other front-line workers who had already spent more than a year caring for coronavirus patients with fewer resources than other GTA hospitals.

Claire Lee, a rehab physiotherapist, speaks to a journalist before helping turn a prone COVID-19 patient to the supine position at Brampton Civic Hospital on May 25, 2021.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

A well-oiled machine

Brampton Civic physiotherapist Claire Lee remembers one of the first times she saw a nursing colleague emerge after helping to flip a patient into the prone position.

It was during the first wave in the spring of 2020, and Ms. Lee, normally a rehabilitation physiotherapist, had been seconded to the ICU to help turn COVID-19 patients.

“His scrubs were soaked,” she said of the nurse. “My first thought was something exploded and got him all wet. It wasn’t. It was sweat.”

Brampton Civic recognized early on that it would have to find creative ways to respond to the sheer volume of COVID-19 patients in its care. Establishing a dedicated team of physiotherapists, including Ms. Lee, to help flip patients in the ICU, was just one of the ways the hospital pivoted to conserve critical nursing resources.

Treating critically ill COVID-19 patients in the prone position is thought to improve their lung function, but patients risk developing pressure sores if they are left on their stomachs too long. Brampton Civic’s approach is to not leave patients on their stomachs for more than 16 hours in a row.

Registered nurse Angel Flores speaking to a reporter about the current pandemic and comparing it to his experience working during SARS.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

“We became like a well-oiled machine,” said Angel Flores, a veteran ICU nurse. At the height of Ontario’s third wave, staff would perform the flipping procedure, “back to back to back to back,” he said. “The team would flip, come out, de-gown and everything, wash up, get ready and go on the next patient. … It was a lot of work and it was scary.”

As of the end of April, Osler had treated 319 COVID-19 patients in the prone position, nearly 10 per cent of the 3,054 infected patients the network admitted between April, 2020, and April, 2021.

Before the pandemic, Brampton Civic’s ICU might have treated a patient or two a month in the prone position, said Michael Miletin, chief of medicine at William Osler.

Flipping was done so rarely that when COVID-19 first hit, a physician was always at the bedside or outside the room to supervise, often reading off a safety checklist that included special attention to the patient’s breathing tube. If the tube came unhooked, even for a moment, coronavirus-filled particles could fill the air and put staff at risk.

“My confidence in our teams has soared,” Dr. Miletin said. When he identifies patients for proning on morning rounds, “they’re right on it. Everyone knows their roles. They’re confident. They have a clarity of purpose. They understand the safety portion of it as well, which is paramount for us.”

Paramedics prepare to transfer COVID-19 patient John Wylie, 76, from Brampton Civic Hospital to Halton Health Care.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

With the pandemic still ongoing, a note taped to a wall at the hospital advises people that no family or visitors are allowed to see patients.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

COVID-19 patient John Wylie is loaded into an ambulance.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Such expertise was essential in the punishing third wave, when Ms. Lee, who returned to her old job during the second wave, was called back to the ICU. By April of this year, Brampton’s ICU had become “like a revolving door,” she said. “You would see people come in on one day, the doctors would stabilize them, and then we would sometimes prone them, sometimes not,” Ms. Lee said. “But then the next day you came in and they were gone.”

Gone, as in transferred to other hospitals. Some were sent as far away as Windsor. In April, the torrent of severely ill COVID-19 patients coming through Brampton Civic’s emergency department refused to abate. At triage, patients were met with signs warning they could be transferred to another hospital.

The transfers, co-ordinated by the GTA Hospital Incident Management System (IMS), were a lifeline for Brampton Civic and other hotspot hospitals, said Dr. Kapoor, who worked on many of the transfer cases.

As of the end of May, 3,219 GTA COVID-19 patients had been transferred since the launch of the GTA Hospital IMS in mid-November, according to Ontario Health. Nearly one-third of all transfers came from William Osler’s hospitals.

The vast majority of families have been patient and understanding about the need to send their infected loved ones out of Brampton, Dr. Kapoor said – in part because relatives generally can’t visit anyway, no matter where a COVID-19 patient is treated.

“The hardest part of this whole process, transfer or not, has been that families can’t visit,” he said. “Families are putting all their trust in your hands. They’re not there. They’re not at the bedside. So it’s been very difficult.”

With the third wave finally ebbing – William Osler’s hospitals transferred out fewer patients in all of May than in the third week of April alone – Dr. Kapoor is hoping other GTA hospitals will continue to help Brampton Civic cope with overcrowding.

But he believes that Brampton, home to his parents and many lifelong friends, deserves better than the chronic health care underfunding that has plagued the city.

“We can’t stand for that.”

With a report from Danielle Webb

Simran Singh is Special to The Globe and Mail

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Kelly Grant

Kelly Grant