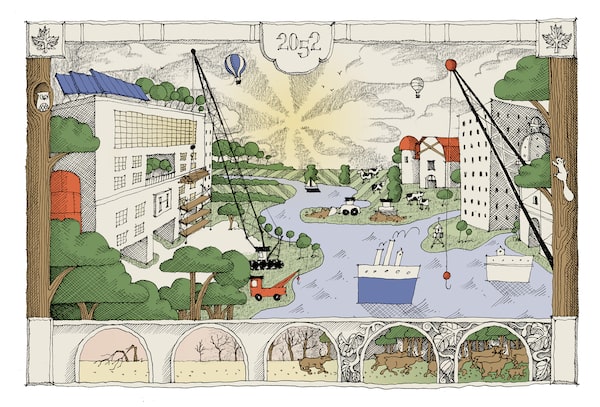

Illustration by Camille Pomerlo

By the middle of this century, and probably sooner, Canada will look and feel like a different place because of climate change.

The question is whether we choose now to ready our people, industries and land in ways that allow us to define that landscape ourselves, maintaining – and in some cases even improving – our quality of life and economic competitiveness.

The urgency of doing so will be highlighted on Monday, when the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change releases its latest report on the impact of rising global temperatures. It will largely tell us what we should know already in a country that last year alone experienced deadly heat waves, devastating floods and an entire town burning down: Those impacts are already being experienced in a multitude of ways, and will only become stronger.

That will point to the need to minimize further climate change by as much as humanly possible, through economic transformation that reduces our greenhouse gas emissions in short order.

But even in the very best-case scenario – which, by international consensus, would contain the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, up from about 1.2 C today – we would still have to reckon with more extreme weather and disasters.

Based on current trajectories, containing the increase to 2 C is a more realistic (and perhaps still optimistic) aim. And that increase stands to be more pronounced in Canada, which is warming at twice the global rate.

There is growing acknowledgment that building resilience to climate change can no longer take a back seat to slowing it; both must happen. That was a theme at last fall’s landmark UN COP26 climatesummit in Glasgow, and the federal government is in the midst of developing Canada’s first national adaptation strategy.

But it can’t just be about waiting for governments to come up with answers. Decisions foisted on communities to address future dangers – from large infrastructure projects to new rules around land use – are liable to be met with resistance if Canadians aren’t engaged from the ground up. A push strategy needs to give way to a pull strategy.

That means empowering the public to start making resilient choices. Canada’s geographic expanse and diversity means different corners face vastly different impacts. When deciding where to live or build, where to invest and what lifestyle changes they might need to make, people need easy access to forward-looking information on risks where they are. And they need better education – from the public and private sectors – on how to safeguard against climate impacts.

At the same time, there should be an opportunity to use our imaginations about what a more climate-resilient Canada could look like.

On Monday the UN will release its latest IPCC report on the impact of rising global temperatures. It will largely tell us what we should know already in a country that has experienced the acute effects of climate change – like the massive wildfires and thick smoke that blanketed B.C. last summer.DARRYL DYCK/The Canadian Press

How could cities be redesigned to be more resistant to floods and excessive heat? How could our relationships with nature and agriculture change? How could we be there for each other when disaster strikes, through emergency preparedness, and new practices in essential services such as health care?

The possibilities are many; the further we look into the future, the more creativity will be needed.

But there are also examples, in Canada and elsewhere, of resilience innovation taking root, and now is the time to start drawing inspiration from them on a broader scale.

Health: ‘Things need to be overhauled’

At the world’s greenest hospital, a low-energy ventilation system circulates air that has been warmed with modular heat pumps and cooled with natural refrigerants. Reusable uniforms are made from an antimicrobial fabric. All waste is processed on site.

Located in the Nordic region of Europe, Grønnköpingkið Hospital is a model of adaptation. By reducing its energy use and dependence on supply chains, the hospital has a better chance of getting through extreme weather events fuelled by climate change without massive disruption. Its backup power generation, for example, will last longer if the facility uses less energy to begin with.

If Grønnköpingkið seems too good to be true, that’s because it is. It’s a fictitious, digital creation, designed by the Nordic Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, headquartered in Sweden, to highlight the technologies and approaches already in use in some hospitals.

“Everybody wants a visionary,” said Daniel Eriksson, the centre’s founder. “But the fact is that there are already solutions that exist today. There are proven concepts.”

Canadian hospital executives and policy-makers at all levels of government are increasingly realizing the need to not just reduce emissions from the health sector, but to adapt to the threats associated with the level of global warming that’s already baked into our present and future.

At last year’s UN climate summit, Canada was among 50 countries that signed onto a World Health Organization pledge to develop climate-resilient and low-carbon health systems. The move acknowledges the risks that climate change brings, from increases in heat-related illnesses that could overwhelm emergency services, to wildfire smoke that could shutter operating rooms, high winds that could take out power sources and flooding that could cut off supply chains.

Paramedics respond to a related call in the downtown Vancouver Eastside during the June, 2021, heatwave that hit the province. The rare "heat dome" claimed the lives of nearly 600 people.DARRYL DYCK/The Globe and Mail

In a recent report on the health of Canadians in a changing climate, the federal government said the overwhelming majority of health care facilities across the country aren’t doing enough to prepare for the risks related to climate change.

This past year in British Columbia is a case in point.

The once-in-1,000-year heat dome that settled over the province in June jammed the 911 system and claimed the lives of nearly 600 people. It laid bare the realities of the urban heat island effect, in which artificial surfaces such as concrete absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes do, causing localized warming. Increasing the tree canopy would mitigate that.

And then in November, flooding of key B.C. highways and bridges meant dozens of people had to be airlifted to receive life-saving dialysis treatment – a consequence of the trend toward centralized health care.

“Adaptation has been neglected for so long,” said Dr. Melissa Lem, a family doctor in Vancouver and incoming president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment. “Things need to be overhauled.”

Extreme weather events in the recent decades have challenged health care systems around the world. Perhaps the most striking example of what can go wrong and how to adapt is the story of the Texas Medical Center in Houston. TMC is the largest medical complex in the world, comprising more than two dozen hospitals and research institutions.

In 2001, Tropical Storm Allison caused critical infrastructure to fail across multiple hospitals. Hundreds of patients had to be evacuated. Research losses from the storm were in the order of US$2-billion.

In the two decades since, TMC hospitals have invested tens of millions of dollars to try to make sure the same thing doesn’t happen again. An on-site combined heat and power plant was installed on the campus, eliminating the dependence on the local energy grid. The power system was also elevated to reduce the chances of it getting flooded.

Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005 also exposed the fragility of hospitals built decades ago. During Katrina, staff had to use furniture to break windows to let in outside air, as indoor temperatures soared. The windows were built to be operable, but they had been sealed shut decades earlier for safety reasons.

The experiences in New Orleans informed the construction of the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston. New York-based health care architect Robin Guenther led the resilience planning and sustainability goal-setting for the hospital, which opened in 2013.

As Ms. Guenther put it, hospital executives “had seen the social media footage from hospitals during and following Katrina and thought, ‘We don’t want to be in that movie.’”

Several critical things were done differently at Spaulding. All the mechanicals – including backup diesel generators, boilers and air ventilation equipment – were put on the roof or on a penthouse level above the hospital floors. The building was raised higher than the once-in-500-year flood level, exceeding U.S. federal standards. And the windows, Ms. Guenther said, can be opened with a key.

One of the first things health care leaders can do to become more resilient in the face of climate change is to understand where their facilities are vulnerable. The Canadian Coalition for Green Health Care has a tool for that, called the climate change resiliency checklist. Hospitals around the world and in at least eight Canadian provinces have used the checklist, which focuses on risk assessment, risk management and building capacity.

Neil Ritchie, the coalition’s executive director and a former hospital executive in Nova Scotia, said he hopes more hospitals will use the tool and make the necessary changes. “We’re starting to understand that this is more immediate than ever,” he said.

The University Health Network in Toronto piloted the resiliency tool several years ago.

Ed Rubinstein, the network’s director of environmental compliance, energy and sustainability, said vulnerabilities were exposed and infrastructure upgrades are under way. Toronto Western Hospital and the adjacent Krembil Discovery Tower are expected to have the world’s largest raw waste water energy transfer system by next year. The hospital is also getting new generators, which will be housed within a weathertight enclosure on a slightly raised platform in a courtyard.

“More than ever before,” Mr. Rubinstein said, “people are motivated to do this.”

– Kathryn Blaze Baum, Environment Reporter

Adaptation planning for agriculture means dramatic investments in infrastructure – everything from water storage, drainage networks, and dikes and seawalls needs to be revisited with an eye toward the long term.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

Agriculture: ‘The most urgent thing is to make a plan’

For the past decade and a half, B.C. has led the rest of the country in adaptation planning for agriculture, with its Climate and Agriculture Initiative BC.

The program is funded by the federal and provincial governments, and brings policy-makers, climate researchers and farmers together to map out the specific risks faced by each region. The program recognizes that the risks faced by farmers vary greatly depending on their region and their type of operation. Crucially, it also offers specific on-farm adaptation strategies for farms.

“It’s a good example of what needs to be done at a national scale,” said Sean Smukler, a professor in the faculty of land and food systems at the University of British Columbia.

It’s the type of detailed, long-term planning that doesn’t exist yet on a national level – at least with the urgency necessary to meet the challenge, Prof. Smukler said. “The most urgent thing,” he said, “is to make a plan.”

The B.C. program’s 2015 plan for the Fraser Valley, for instance – the area hit hardest by floods last year – had specifically warned of risks of flooding, both from extreme precipitation and snow melt. It urged farmers to prepare and to plan for the potential of crop loss, the need to relocate livestock, and the possibility of flooded roads and interruptions to supply chains.

Even so, those plans didn’t predict the severity of last year’s weather events – and the fact that they’d arrive so soon, said Prof. Smukler. “And with that the planning and investment has not been enough in magnitude, or speed,” he said.

In many cases, that means dramatic investments in infrastructure – by farmers on their properties and by governments. Everything from water storage, drainage networks, and dikes and seawalls needs to be revisited with an eye toward the long term.

“These are kinds of things farmers can’t do on their own,” he said. “This has to be a societal investment.”

Still, there has been some progress. Twenty years ago, when University of Guelph climate researcher Barry Smit gave presentations to policy-makers, or to farmers about adapting to climate change, the question he often heard was: “But is there really climate change?”

Flood waters surround barns in Abbotsford, B.C., in November, 2021. The B.C. program’s 2015 plan for the Fraser Valley had specifically warned of risks of flooding, both from extreme precipitation and snow melt.JONATHAN HAYWARD/The Canadian Press

At the very least, the conversation he’s met with by farmers now is: “Yes, [climate change] is here. What can we do about it?”'

“[Back then], People were looking to go back to normal,” he said. “I think now it’s pretty obvious we’re not going back to ‘normal.’”

Prof. Smukler said the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has helped to hasten that along.

The shortages experienced in early 2020 helped to illustrate to the general public the importance of building resilience into the agricultural system – preserving local food production, and protecting the country’s food sovereignty.

“When we talked [before] about agriculture, peoples’ eyes glaze over and they think it’s only a small sector of our economy,” Prof. Smukler said. “[They’d think] ‘We don’t really need to deal with this, we’ll just get our food from somewhere else.”

But the pandemic has helped people understand what happens when the ‘somewhere else’ is affected, too.

“If we don’t deal with our own capacity to adapt, then we’re trusting that California’s going to deal with its problems,” he said. “Otherwise, we’re going to be eating something other than the lettuce during the wintertime.”

– Ann Hui, National Food Reporter

Flood preparations will include expensive and disruptive renovations to safeguard our buildings, and may even involve relocating neighbourhoods and entire towns now on land that is becoming too flood-prone to safely inhabit.DARRYL DYCK/The Canadian Press

Flooding

Nowhere is there a greater need to level with Canadians about the risks they face, and to strike common purpose in reconfiguring communities to avert disaster, than when it comes to climate-related flooding.

Even as catastrophes such as last year’s devastating rainstorms in B.C. offer a terrifying preview of what lies ahead – and the government-funded Canadian Institute for Climate Choices predicts a fivefold increase in flood damages to homes and other buildings by mid-century – many people facing the greatest danger have been kept in the dark. The country’s flood maps are woefully out of date and difficult to access, and data is not made clearly available in real estate listings or other places it could help with informed decisions.

Placing such information at our fingertips – which the federal government has pledged to do, through updated flood maps at least – will make for some unpleasant realizations about what the future holds and how to prepare for it.

Those preparations will certainly include expensive and disruptive renovations to safeguard our buildings and, at a larger scale, investments in critical infrastructure such as flood walls. They may even involve relocating neighbourhoods and entire towns now on land that is becoming too flood-prone to safely inhabit.

Mario Loutef cleans up after his home was flooded in Princeton, B.C., on Nov. 20, 2021. The Canadian Institute for Climate Choices predicts a fivefold increase in flood damages to homes and other buildings by mid-century.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

But engaging people in at-risk areas in building flood resilience can also involve discussing how to make our homes and communities more visually appealing, improve quality of life and reduce social inequalities.

Consider the growing movement toward green infrastructure to capture rainwater.

In general, the idea is to strategically place absorbent greenery in locations where there is lots of runoff from heavy rain or melting snow. That can mean rain gardens, consisting of deep-rooted plants in shallow depressions, on public or private lands. Or greenery atop the roofs of houses and larger buildings. It can be as ambitious as changing the look and feel of entire city throughways or as modest as rain barrels outside homes.

While European countries such as the Netherlands have been at the forefront of this approach, Canadians can look south of the border for lessons about how to embrace it on a large scale.

Philadelphia is currently in the midst of spending more than US$2-billion on its 25-year Green City, Clean Waters plan, which aims to use primarily natural means to manage rainfall accumulation across 10,000 city acres. It was launched in 2011, when the city was required by U.S. environmental regulations to address its sewer overflows – a growing problem for many cities whose sewer systems handle both storm and sanitary waters.

In an interview, Paula Conolly, who helped lead the strategy for Philadelphia’s water department and is now director of the Green Infrastructure Leadership Exchange, said the city was drawn to the green approach because it promised to be less expensive and less disruptive than just building more traditional water infrastructure. It also would bring “bonus value” to communities.

Extreme flooding prompted the evacuation of the city of 7,000 in Merritt, B.C., in Nov. 2021. Last year’s devastating rainstorms in B.C. offer a terrifying preview of what lies ahead.ARTUR GAJDA/Reuters

Beyond flood prevention, those bonuses include a more attractive cityscape, better air quality and mitigation of the growing threat from extreme heat. The upsides can be especially pronounced in poor neighbourhoods, which tend to have higher flood risks and less green space than affluent ones to begin with, adding a social equity dimension.

The program has been sufficiently successful thus far, at least in its most measurable goal of reducing the amount of untreated waste entering the city’s waterways, to have encouraged U.S. cities such as Washington D.C. to go down similar paths. But it’s also been a learning experience, from which others can draw.

“Probably the biggest advice is not to underestimate the total culture shifts that are required to make something like this happen,” Ms. Conolly said. That includes a shift in thinking across multiple city departments more accustomed to traditional infrastructure projects, stronger relationships between government and residents to generate uptake and get greenery where it’s actually wanted, and ensuring the new green spaces are well-maintained rather than allowing them to become eyesores that create backlash.

Here in Canada, there are some promising efforts, though more nascent. Vancouver’s Rain City Strategy, adopted in 2019, is probably the most ambitious of them. It aims to have 40 per cent of the city’s impervious surfaces covered by green infrastructure by 2050. Initial projects have run the gamut, from rain gardens to green roofs to tree planting. But early spending of about $10-million per year, on about 60 community projects thus far, is a drop in the bucket compared with some of the U.S. cities.

Other Canadian cities are at least starting to experiment. Kitchener, Ont., for instance, has partnered with a local environmental charity to offer education, training and modest incentives to hundreds of potential early adopters interested in installing rain gardens or other forms of absorption at their homes.

It’s about “showing people they can take individual action,” said Emily Amon, who runs water programs for Green Communities Canada, which works with Kitchener and other cities on such programs. And the more that the action is taken on private property, she suggested, the more it will demonstrate support for larger public investments in green infrastructure as well.

By no accounts will green infrastructure do all the heavy lifting, in making communities more flood-resistant. But it could reduce the need for other, less enticing ways of going about that. And alongside better informing Canadians about the risks they are facing, it could move us toward a more collective effort to tackle them.

– Adam Radwanski, Climate Policy and Politics Columnist

Nature and Conservation

Climate change is not the only threat to Canada’s wildlife, but it is becoming a more significant one. Forests, tundra, and freshwater and marine ecosystems are all changing in a multitude of ways that tilt the scales for some species at the expense of others, and threaten to upend national conservation goals by altering the environments those goals are based on.

This is especially apparent in the North, the part of Canada that is warming fastest and far more than the global average. There, the transition includes more intense wildfires, the “shrubification” of the Arctic as woody plants migrate north of the treeline, and the widespread muddying of rivers and lakes as shorelines that are no longer supported by permafrost erode and collapse, threatening fish populations.

“We can see the front line of the crisis here, where our species are really struggling,” said Chrystal Mantyka-Pringle, a conservation planning biologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society Canada who is based in Whitehorse, Yukon.

For biologists and land use planners alike, the future of Canada’s natural landscapes is becoming more dynamic and less certain. There is also a growing recognition by governments and other stakeholders that nature is not a side issue, but a crucial pillar for developing the country’s overall climate resilience. That has put a premium on strategic thinking about actions that have multiple benefits for nature and for people.

“We’re seeing a needed change in the conversation,” she said. “The idea is, if we’re thinking long term, we can build resiliency back in the system and restore biodiversity.”

A key feature of the discussion is about conserving what remains as well as extending conservation measures to larger areas. That means taking into account the need for plant and animal species to shift their ranges in response to climate change – particularly in a south-to-north direction or from lower to higher elevations. It also means paying more attention to corridors that connect wild places in a way that keeps species populations from becoming isolated from one another.

“That’s something we really have not done a very good job with here in Canada,” said Kai Chan, a professor at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia, who added that forestry and agricultural practices that enable wildlife movement “need to become the norm.”

Researchers are also working to identify areas that will act as “climate refugia” – places where local and regional geographic factors will help buffer them against climate change and allow them to act as available habitat when other areas become less favourable.

In the boreal forest, which accounts for a large fraction of Canada’s total land area, potential climate refugia include wetlands, mountains, large lakes and coastlines – all of which should be considered when allocating areas for future protection.

Conservation groups say the payoff is that protecting nature also aligns with Canada’s climate goals. For example, the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay is among those areas that fit the criteria for a natural climate refuge. It also sits atop a vast storehouse of carbon in the form of peat, which has the potential to exacerbate climate change if it’s disturbed. Protecting the region from development also helps Canada to meet emissions targets.

Forests, tundra, and freshwater and marine ecosystems are all changing in a multitude of ways that tilt the scales for some species at the expense of others, and threaten to upend national conservation goals.David Goldman/The Associated Press

Dr. Mantyka-Pringle said one positive side effect of climate change making itself felt in the North is that innate resilience in some areas is revealing itself. For example, while many lakes and streams are facing increased water temperatures and erosion problems, others are not, which in turn helps researchers to identify what factors contribute to resilience and helps prioritize areas for protection.

The challenge for Canada is balancing the need for long-term thinking with an economy that has historically been focused on resource extraction on much shorter timelines. This is one reason why many researchers and environmental groups support a shift toward Indigenous-led conservation – which stresses the connectivity of life and very long time horizons.

In some cases, conservationists are looking at more direct measures, such as assisted migration, to deliberately move trees and other species outside of their natural ranges into areas where climate models show they will be better able to survive in the future. More controversial still is the concept of rewilding – bringing back lost species using archived DNA to help complete an ecosystem.

Dr. Chan said one potential candidate for such an extraordinary measure would be Steller’s sea cow, a marine species that was once a top grazer in the kelp forests of the Pacific Northwest but was driven to extinction in the 18th century.

The same region has recently seen the return of sea otters, an ecological success story that has now created an issue for local shellfish harvesters. What’s missing from the picture is sea cows, whose grazing habits once shaped the ecosystem in a way that afforded shellfish more protection, Dr. Chan said.

“We have become quite convinced that if you could restore sea cows to these systems that it could make them much more productive and much more resilient to a range of different kinds of impacts,” he said.

– Ivan Semeniuk, Science Reporter

This article is part of No Safe Place, a year-long Globe project on climate adaptation in the wake of a string of climate-related disasters in Western Canada.