Good morning, and welcome to the weekend.

Grab your cup of coffee or tea, and sit down with a selection of this week’s great reads from The Globe and Mail. In this issue, Joe Castaldo looks at how artificial intelligence learns. Castaldo began writing this story in May after noticing job postings looking for experts to train large language models to become better in a range of fields, such as science, marketing, law and creative writing. From there, he learned there were a number of people behind the scenes who helped powerful applications such as ChatGPT work properly. Many were freelancers or independent contractors, most of whom also had no idea who their clients were or what the end product was that they were working toward. “I kept thinking of the TV show Severance, where the characters spend their days underground at computer terminals, completely in the dark about what their jobs are,” Castaldo said. “A couple of people I spoke to joked that they sometimes wondered if they were really helping to train AI models – or whether the roles were actually reversed.”

If you’re reading this on the web, or it was forwarded to you from someone else, you can sign up for Great Reads and more than 20 other Globe newsletters on our newsletter sign-up page. If you have questions or feedback, drop us a line at greatreads@globeandmail.com.

Meet the gig workers making AI models smarter

KUBA FERENC/The Globe and Mail

Artificial intelligence can seem like magic. A lot of us experienced an uncanny thrill first seeing ChatGPT write a coherent paragraph or an image generator render a photorealistic picture. But somewhere along the line, people had to label a data set of images so that an AI model could learn that a cat is a cat and a tree is a tree. When you look behind the curtain to glimpse how some AI models are made, it’s clear how crucial we are to the process. We are the ghost in the machine – but maybe not for long. Joe Castaldo dives into how AI models are trained and how they learn.

After earthquake, Morocco’s trust in king and country is shaken by slow relief efforts

A general view of damaged and destroyed buildings, in the aftermath of a deadly earthquake, in Amerzagane, Morocco Sept. 15, 2023.AMMAR AWAD/Reuters

For days after the destruction wrought by the magnitude-6.9 earthquake, which killed at least 3,000 people across their mountainous region and caused serious damage across much of central Morocco, King Mohammed VI was nowhere to be found. When he resurfaced, he authorized only aid teams from Britain, Spain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to enter Morocco – an explicit snub to disaster-aid superpowers Canada, France and the United States, which are typically able to mobilize vast resources quickly. Now, Moroccans devastated by the earthquake are asking what their king is doing to help them.

Chief of Staff to the Prime Minister Katie Telford arrives to appear as a witness at the Public Order Emergency Commission in Ottawa, on Nov. 24, 2022.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

In politics, some prime ministers employ their chiefs of staff as mercenaries for specific moments and replace them when the situation demanded something different. Others have held their chiefs close for years as trusted consiglieres. But none have lasted longer than Katie Telford, who has run Justin Trudeau’s office since the 2015 election that swept the Liberals into power: eight years in October. Shannon Proudfoot profiles Telford, the longest-serving chief of staff in PMO history – and one of the most powerful people in the country.

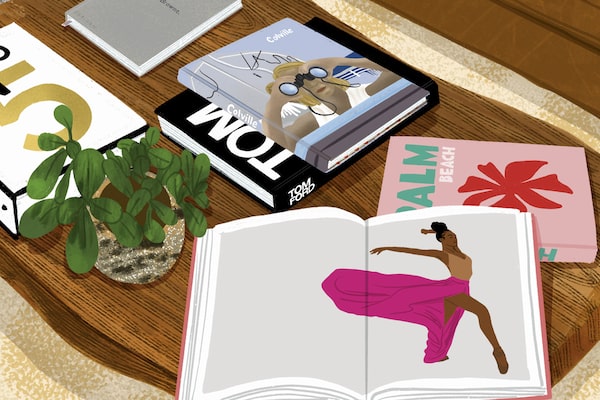

The coffee table book is here to stay

Illustration by Salini Perera

Coffee-table books, be they opulently crafted and outsized or stylistically subtle, are too good at revealing who we are – or who we want to be seen as – to be on the outs. And they’re too fulfilling not to savour on a rainy afternoon at the cottage, transporting us to a wanderlust-worthy destination or revealing luscious photos and factoids about favourite chefs, musicians and makers. Odessa Paloma Parker writes about their enduring popularity, arguing that as publishers appeal to younger generations, the interior accessories, which can represent varied identities, are more collectable then ever.

Coups in Niger, Gabon and beyond signify the real end of France’s empire in Africa

Torn campaign posters of ousted Gabon President Ali Bongo Ondimba and his political party the Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG) in Libreville on Sept. 7, 2023.-/AFP/Getty Images

Africa is at a major inflection point, and Richard Poplak says it may turn out to be more consequential than the Arab Spring in 2010. The region has tipped into something new, a moment where liberation from France becomes a possibility. But the negotiations will take place in an environment of deep chaos, where military juntas preside over a destabilized region, and the vacuum left by fading France is filled with something else, not yet named and not yet defined.

To save the future from food insecurity, we should look to cuisine of the ancient past

In this 1937 reproduction of an ancient Spartan cup, workers package silphion for export under the eyes of Arcesilaus I of Cyrenaica, seated at left, who reigned in the 6th century B.C. Cyrenaica, in what is now eastern Libya, was the Greco-Roman world’s only supplier of the plant until its apparent extinction.Supplied

Many people know that the world is undergoing a huge drop in biodiversity. According to some estimates, a quarter of the 8.7 million known plant and animal species alive today are likely to become extinct by century’s end. What fewer people are aware of is the fact that agrobiodiversity – the range of plants and livestock that feed us – is also in decline. Three years ago, Taras Grescoe set out on a round-the-world quest for nine lost, endangered, and ancient foods, spanning the history and prehistory of our species. Now, he writes about the gravest threats to the world’s food supply.

Globe and Mail reporter Josh O’Kane (L) is photographed with and Chris Abraham (C) and Michael Healey (R), at the Crow’s Theatre on Sept. 12, 2023.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Sideways was an investigative post-mortem of the failed attempt by Sidewalk Labs to build a neighbourhood on the Toronto waterfront; it doubled as an exploration of tech companies’ intrinsic incompatibility with how cities are run. But playwright Michael Healey’s The Master Plan, based on the book, rooted itself in comedy. Josh O’Kane writes about seeing his book investigating the Sidewalk Labs saga as a play – and a master class in storytelling for the stage.

Bonus: Take our arts quiz to test your knowledge of the latest arts and culture news.

Aerosmith postponed their concert in Toronto because Steven Tyler was suffering from what condition?

a. Peptic ulcer

c. Rheumatism

d. Old age