If you’re reading this on the web or someone forwarded this e-mail newsletter to you, you can sign up for Globe Climate and all Globe newsletters here.

Good afternoon, and welcome to Globe Climate, a newsletter about climate change, environment and resources in Canada.

We know the importance of eating so we have a healthy body, but what about eating for a healthy planet?

For example, lentils, like other pulses, including chickpeas and beans, naturally enrich soil with nitrogen, reducing the need for petroleum-based fertilizers. That’s a good thing because the manufacture of these fertilizers emits CO2 into the atmosphere.

But as climate change progresses, how do we help lentils adapt to higher temperatures? A plant scientist team at the University of Saskatchewan is working on the answer to that, using the study of genomics. Read about how they are decoding lentils here.

Now, let’s catch you up on other news.

Noteworthy reporting this week:

- Taking the farm to Instagram: How four women farmers are connecting through social media

- B.C. adopts emergency alert system for disasters, but not extreme heat

- In wildfire country, towns build permanent evacuation centres

- Activist investor vows to continue climate push after Enbridge shareholders reject proposal

- From The Narwhal: Emails reveal how the RCMP changed its story about arresting journalists in Wet’suwet’en raid

A deeper dive

Hunting for frozen assets

Ivan Semeniuk is The Globe and Mail’s science reporter. For this week’s deeper dive, he talks to scientists about the trek to monitor Canada’s ice records ahead of their departures for this year’s field season.

Every spring, scientists who study Canada’s glaciers head up to the High Arctic and to the western mountains to take the measure of the giant frozen formations they study.

It is an annual ritual that provides crucial data for the long-term tracking of Canada’s permanent ice. This year it also served as the genesis for a story about how and where this important monitoring work is conducted and how it informs our understanding of the growing impact of climate change.

As The Globe and Mail’s science reporter, I needed to prepare for the story, so I spoke with four teams of scientists just days ahead of their separate departures for various glaciers across Canada.

Gwenn Flowers (left), SFU PhD student Erik young (right) use ice-penetrating radar survey to measure ice depth on an unnamed glacier, July 2021SFU

Two of those teams are led by federal scientists who return to the same sites each year in order to document what the glaciers are doing today relative to previous decades. One group is leap frogging across the Arctic Archipelago where Canada’s largest ice caps reside. These are globally important formations because, after Antarctica and Greenland, they represent the largest volume of stored ice in the world. As they lose size and mass, they are becoming significant contributors to sea level rise.

In the high elevation valleys and plateaus of the west, scientists are also studying the glaciers that make up what is sometimes called Canada’s “second Arctic.” Some are well known tourist attractions, like the Columbia Icefield of Alberta. Others, like the Bologna Glacier of the Northwest Territories, are rarely seen by anyone.

Coline Ariagno in a snowpit in the icefields measures the seasonal snow accumulation, May 2016.SFU

Data from all of these reference sites are provided by Canada to the World Glacier Monitoring Service where they are incorporated into planet-wide models of global warming.

Meanwhile, university-based researchers are also engaged in studies of glaciers in Kluane National Park and Reserve, home to Canada’s highest mountains. My story includes a team from the University of Alberta that is climbing the mountain this month in an effort to extract an ice core from a glacier near the summit. Scientists believe the ice core could provide a climate record that reaches back more than 30,000 years. If they’re successful, you’ll see me write about that in this newsletter.

- Ivan

What else you missed

- Heat wave in India sparks blackouts, questions on coal usage

- Fisher River rises, causes more damage in flooded Manitoba community

- B.C. highway blockades over old-growth logging aimed at forcing a dialogue, activists say

- Last summer’s B.C., Alberta heat wave was among most extreme since 1960s, study shows

- Sandstorm suspends flights, many Iraqis struggle to breathe

- Polar bear experts say killing animal in Quebec was necessary, standard practice

Opinion and analysis

Eric Reguly: Anglo American’s departing CEO Mark Cutifani anticipated mining’s move to ESG principles - and saved his company along the way

Green Investing

Suncor’s safety records overshadow the oil company’s ESG efforts

Suncor Energy Inc. and its chief executive officer Mark Little currently face a challenge in a campaign by U.S. activist investor Elliott Investment Management LP to force change at the company, install five new directors and possibly oust Little himself.

Elliott, which said last week it had amassed a 3.4-per-cent stake in Suncor, has no beef with Suncor’s environmental initiatives such as Oil Sands Pathways or efforts to use less energy in operations and to reclaim mine sites. As a company that often says ESG is a key part of how it operates, this will be a case of showing how Suncor can bring “G” – governance – to bear to solve the safety problems that Elliott has made into a very public issue.

- Also: Sustainability is a competitive advantage for Canada’s Greenest Employers 2022

Making waves

Each week The Globe will profile a Canadian making a difference. This week we’re highlighting the work of Sofia Bonilla making sustainable pet food.

Sofia BonillaSupplied

My name is Sofia Bonilla, I’m 37, live in Mississauga, Ont., and have been in academia at the intersection of biology, environment and engineering for 15+ years. I earned a PhD from the University of Toronto and my research now focuses on finding novel ingredients for sustainable food.

Plants don’t have all the nutrients pets need and with the increasing demand for meat and fish in pet food, our pets’ environmental pawprint will continue to increase. I created Hope Pet Food, which tackles the environmental impact of pet food by removing livestock and fish, while still providing all the nutrients pets need. It’s high in protein and is also hypoallergenic. We go beyond plants and use insects, algae and fungi.

I transitioned from academia to entrepreneurship because I’m convinced businesses have a responsibility to address the climate crisis. Now I use my background in science to lead the transition into a better and more sustainable future for pet food.

- Sofia

Do you know an engaged individual? Someone who represents the real engines pursuing change in the country? Email us at GlobeClimate@globeandmail.com to tell us about them.

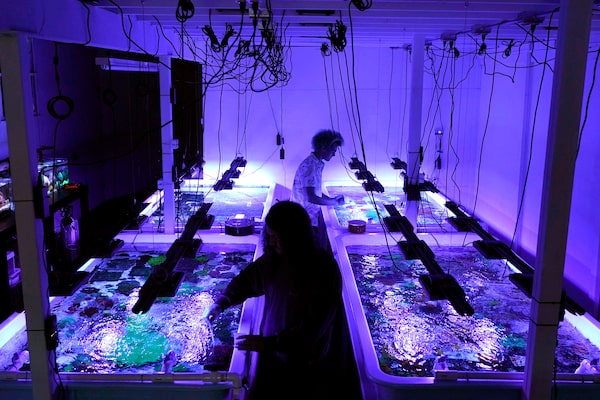

Photo of the week

Marine biologist Colin Foord, rear, and musician J.D. McKay work at their Coral Morphologic lab, Wednesday, March 2, 2022, in Miami. They have been on a 15-year mission to raise awareness about dying coral reefs with a company that presents the issue through science and art.Lynne Sladky/The Associated Press

Guides and Explainers

- Want to learn to invest sustainably? We have a class for that: Green Investing 101 newsletter course for the climate-conscious investor. Not sure you need help? Take our quiz to challenge your knowledge.

- We've rounded up our reporters' content to help you learn about what a carbon tax is, what happened at COP 26, and just generally how Canada will change because of climate change.

- We have ways to make your travelling more sustainable and if you like to read, here are books to help the environmentalist in you grow, as well as a downloadable e-book of Micro Skills - Little Steps to Big Change.

Catch up on Globe Climate

- Inuit knowledge and science skills fight climate change in the Far North

- Across the African continent, climate crises inflict suffering on millions

- An investigation into the murky world of ESG ratings

- To stop allergy season from getting worse, mitigate climate change

We want to hear from you. Email us: GlobeClimate@globeandmail.com. Do you know someone who needs this newsletter? Send them to our Newsletters page.