This is the first of a three-part series following glacier researchers from British Columbia’s Coast Mountains to the lab as they try to unearth climate history. In Chapter 2 and the Decibel episode below, reporter Justine Hunter explains more about what they are looking for.

The summit of Mount Waddington rises out of British Columbia’s Coast Mountains range like a monstrous fang. Standing on the flat saddle of Combatant Col, one kilometre below the mountain’s peak, the thick ice below crackles and rumbles, imperceptibly flowing. This is a birthplace of glaciers.

The mountain has called to elite alpinists since the 1920s. At 4,019 metres, Mount Waddington is the highest peak that is fully within B.C.’s borders. It lies just 300 kilometres northwest of Vancouver, yet it is hidden amongst a series of spectacular ice-clad pinnacles, and defended by broad icefields.

The first attempts to climb Waddington – once dubbed “Mystery Mountain” – yielded false summits, wicked rock, violent weather and death. Those legendary tales sparked the interest of mountain climber and glaciologist Eric Steig, who understood that the conditions that made the mountain so challenging for mountaineers would also preserve hundreds of years of valuable climate records in the ice. Dr. Steig, a professor from the University of Washington’s Department of Atmospheric Sciences, has been working to extract an ice core here since 2004.

This summer, he and a small team of Canadian and American researchers camped on Combatant Col, hoping to find new insights into the changing climate buried by centuries of heavy snowfall.

While ice core science is well-established in the Antarctic and Greenland, a deep environmental archive hasn’t been tapped this far south in North America. That’s partly due to the fact that these temperate glaciers don’t easily give up the wealth of information they hold. Just like the early climbers, the scientists found Waddington a formidable challenge. “This mountain has a history of defeating people,” Dr. Steig noted.

The team of Canadian and American researchers set up camp on Combatant Col. and prepare for the difficult task of extracting an ice core.Grant Callegari/Hakai Institute

If successful, a deep sample of the ice from the southern Coast Mountains would fill in some of the large gaps in the historic climate record in the Pacific Northwest. For example, researchers might discover patterns of annual precipitation that can help us understand if this year’s drought conditions are part of a larger cycle.

And, critically, researchers hope to learn about the frequency and intensity of wildfires in centuries past. Canada’s wildfire season this year has consumed more than 18 million hectares of forests – eight times the average rate of destruction. Based on the limited data available, fires in Canadian forests appear to have been getting larger and more destructive, and the fire season is getting longer, over the last half century.

“We really don’t know how extreme these last few years have been in the long-term context,” Dr. Steig said.

The Globe and Mail is following this project from the icefield to the laboratory, to help understand the string of climate-related events, from deadly heat waves to catastrophic floods and fires, that are buffeting Western Canada.

The Globe toured the camp on July 9, when Mount Waddington’s capricious weather provided a rare moment of sunshine and still winds. Around the province that day, however, parched by drought and unusually hot weather, lightning storms sparked 89 new wildfires, and thick clouds of smoke were visible to the north. The previous week saw global heat records set. All of this lends a sense of urgency to the researchers’ work, as Canada’s glaciers retreat in the face of climate change.

The ice cores collected from this glacier will give them a window into annual temperatures, precipitation and airborne contaminants, in a region where such records are sparse at best. It could help calibrate the recurring climate patterns that drive changes in the temperature of the Pacific Ocean, which govern the ocean’s ability to support life. And it may reveal changes in forest fire activity over time.

Ground-penetrating radar scans indicate the ice on the col is 250 metres deep, which could hold 1,000 years of environmental history. The annual layers of precipitation are compressed by the weight of accumulated snow and ice, so the deepest ice is the most valuable, with far more historical data than the top layers.

The researchers – from the U.S. Ice Drilling Program, the University of Northern B.C., the University of Minnesota, the University of Washington, and the Hakai Institute – hoped to go back at least to the year 1850, when carbon dioxide emissions from human activity were just a tiny fraction of what they are today.

Despite the team’s extensive experience drilling for polar ice cores, the conditions here are uniquely challenging. Moisture carried from the Pacific Ocean dumps so much snow here each year that the most valuable records are deeply buried.

But there’s advantages that come along with the difficulties. The summer melt gets locked into the colder layers below – preserving the distinct chemistry and texture of each year’s snowfall, rather than washing it away. “That’s our best understanding of why this place works for an ice core record. And an ice core record that’s way further south than any other in North America,” said Peter Neff, glaciologist and climate scientist from the University of Minnesota, who led the three-week expedition on the mountainside.

This was the second time Dr. Neff and Dr. Steig teamed up to collect an ice record at Combatant Col.

On their first attempt, in 2010, the team cored 140 metres deep into the ice. But because the top layers are so thick, that only took the record back to 1973. It did prove, however, that this ice can produce quality records – in fact, researchers were able to chart the impact of phasing out leaded gasoline, which Canada banned in 1990, in the annual layers.

But Dr. Steig and others knew there was far more data buried on Combatant Col, if they could get down to bedrock. One thousand years is not that old compared to ice cores taken in colder parts of the planet, but it would be invaluable data for this region. The oldest weather records in B.C. collected by Environment Canada go back to 1840, but those are very limited compared to what can be found in the Coast Mountains.

“What we found last time, was that there are beautifully-preserved seasonal variations in the chemistry,” Dr. Steig said. “So we’ll measure that and, with any luck, we’ll be able to count layers all the way down to the bottom and then we’ll be able to say okay, it’s 100 years old, or it’s 300 years old, or whatever the number turns out to be.”

Climate Innovators and Adaptors

This is one in a series of stories on climate change related to topics of biodiversity, urban adaptation, the green economy and exploration, with the support of Rolex. Read more about the Climate Innovators and Adaptors program.

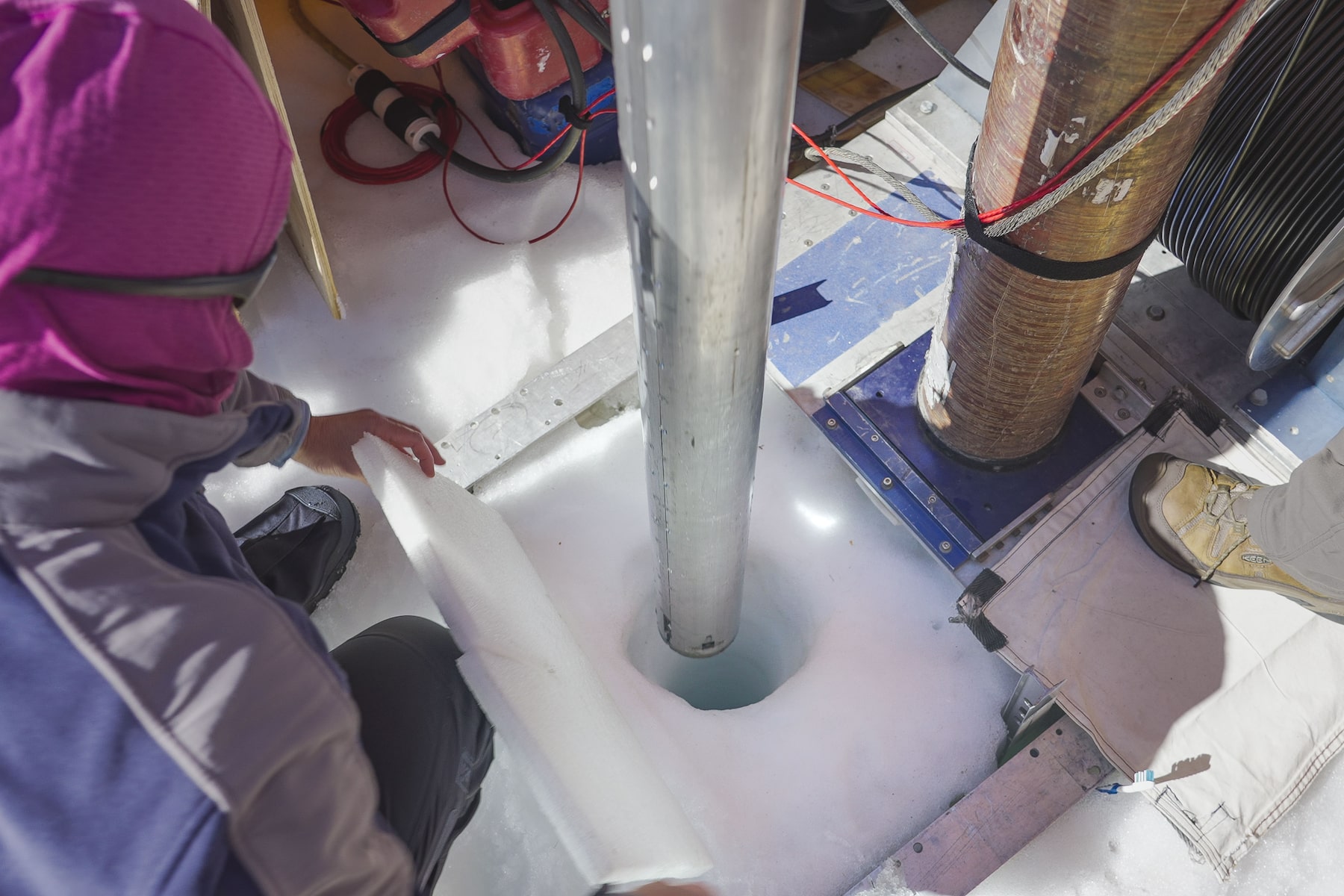

The heart of the 2023 expedition, which began June 20, was a tall, open tent where a trio of researchers extracted cores of ice using a barrel-shaped, heated drill. The cores were hauled up in sequential lengths, with delicate claws deployed inside the barrel of the drill to grip the slippery and precious payload.

Two weeks into the expedition, the team was feeling good. “We hit 200 metres deep,” Dr. Neff recalled. “Everybody was starting to bet on how deep it was – we might have jinxed ourselves.” The next day, the drills were stalled at 208 metres by an unknown obstruction.

The drillers backed up part-way, and then started a new borehole at a slight angle, making their way past the obstacle, allowing them to collect deeper samples. By the third week, the mood was upbeat again. They were getting closer to bedrock each day, and the bets were back on. The winner would get the first shower - a prize after all these days on the ice - and some swag from their helicopter contractor.

Every metre or two, the researchers would pause drilling to pull a chunk out, and mid-morning on July 9, another cylinder of ice was hoisted out of the deep, and delicately eased into a cradle. This ice section came from a depth of 215 metres. It would have last seen daylight, mostly likely, in the 1800s.

“It’s a magical little porthole,” Dr. Neff said. “This is like finding a written record of the past.”

The Ice cores, stored in steel containers, will be airlifted down to the B.C. interior, where a freezer truck will keep them preserved until they are delivered to the Canadian Ice Core Lab in Edmonton.Supplied

The camp sat at 3,000 metres above sea level, where there is less oxygen in each breath – and exertion is notably more difficult. There are risks of avalanche, of new crevasses opening up. Each morning the crew would re-secure their tents, as the wind swept away the snow that helped them anchor the shelters that were vital to their survival here.

The pandemic almost convinced Julia Andreasen, a PhD student at the University of Minnesota, to abandon her studies in ice core paleoclimatology, because there have been so few opportunities for field work. This experience has reinvigorated her. “It’s pretty cushy living when you get to wake up and see two incredible mountains on either side,” she said. The camp was set between the sheer rock faces of Mount Combatant and Mount Waddington. In between, the ice drops off to the Tiedemann Glacier to the southeast, and Scimitar Glacier to the northwest.

Ms. Andreasen’s next field trip will be to the Antarctic, and this has been good training. It has also forged a link in her mind between studying paleoclimate records, and human aspects of climate change. The environmental changes charted in the ice at Combatant Col are important to the millions of people living in this region of southern B.C.

Glaciologist Brian Menounos, examines one of the freshly excavated ice cores.Justine Hunter/The Globe and Mail

Glaciologist Brian Menounos, from the University of Northern B.C. and the Hakai Institute, is the third research lead. He held up one of the freshly excavated cores to the sun, looking for any variation that might hint at wildfire activity.

British Columbia has endured a string of climate catastrophes in the past three years. Too much rain at times, not enough at others. Heat domes and conflagrations. In 2023, an early heat wave melted off the snowpack early and most parts of the province are experiencing sustained, record drought – factors that have exacerbated the devastating wildfire season. The almost 18 million hectares burned across Canada at last count is a record year of destruction – and more than a quarter of that was in B.C. and Alberta.

All of this will hasten the loss of Western Canada’s glaciers, which Dr. Menounos has been tracking through aerial surveillance. But little is known about the longer patterns of drought and wildfire. “We know that we have altered the natural variability, but we still need to know what that natural variability is, to put current events in a long-term perspective.”

Researchers hope a deep sample of ice from the southern Coast Mountains would fill in some of the large gaps in the historic climate record in the Pacific Northwest.Peter Neff/Supplied

The drilling ended on July 12 at a depth of 219 metres, stalled by thick bits of granite and sand in the ice. A borehole camera was dropped down the narrow hole, but it only confirmed that the way was blocked. “We had exhausted all of the options,” Dr. Neff concluded. After three weeks of effort, it was time to pack it in. They came away with an instrumental record longer than any other in British Columbia, although it wasn’t the ending they were hoping for.

“We actually don’t know, and perhaps never will know for sure, how many metres off the bedrock we are,” Dr. Steig said. “We might be at the bottom, but we might be another metre or two or even five. What’s frustrating is that could be quite a lot of time that’s still left there.” He believes the records they did collect go back to some point in the 1800s, at least, but the timeline needs to be confirmed in the lab.

The expedition wrapped up just as wildfire smoke enveloped the col.

“The last morning, it was only three of us up there, waiting for the last ride out,” Dr. Neff recounted. It was an apocalyptic backdrop, as they raced to preserve their frozen records. A freezer truck was waiting below on the Chilcotin plateau for the final helicopter load of ice cores. The truck would then have to navigate a landscape of wildfires from the coastal range to the Canadian Ice Core lab at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, where they can be preserved at a temperature of -40 Celsius.

“Reconstructing wildfire smoke in the ice cores is one of our higher priorities,” Dr. Neff said. “And here we were, trying to keep the glacier ice alive down in the fiery, smoky, hot Chilcotin. It is just pretty crazy.”

Members of the research team stand on Combatant Col, where they spent June and July collecting ice cores from the glacier.Peter Neff/Supplied

Podcast: Justine Hunter on The Decibel

Glacial ice can offer clues about the climates of eons past. But how do researchers collect, store and analyze them? On this episode of The Decibel, reporter Justine Hunter explains. Subscribe for more episodes.

Up next, Chapter 2: A race against time

Glaciers foretell our future – and they’re disappearing fast. By helicopter, the up-close view of B.C.’s coastal mountains is stunning. Black spires of rock and azure lakes stand out amid endless icefields. But Brian Menounos, one of Canada’s leading authorities on glacier change, looks out the window and sees what is coming in the future: “It’s hard to believe so much of this will be gone by the end of the century.” He is part of a Canada-U.S. team of researchers, racing to capture the environmental history contained in these glaciers, before they are gone.