Matthew Hough, engineering director for the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, is in an arms race with Mother Nature.

This year, his crews are busy raising a road in Fort McMurray that runs alongside the Clearwater River, one of two major waterways running through town. Once it is elevated, it will do double duty as a dike and a major arterial road – all part of a network of flood defences currently under construction or being designed in this northern Alberta city.

This race is one that Mr. Hough intends to win.

Asked what existed before, he laughs, before saying, “Nothing. There simply wasn’t these kind of defences in place.”

If all goes according to plan, in a few years Fort McMurray will be a walled city. The anticipated cost: nearly $300-million.

To put that figure into perspective, consider that a 2006 provincial committee recommended a suite of flood-mitigation measures across the entire province – safeguarding 54 municipalities – whose total cost was just more than $300-million. The price tag for Fort McMurray, which Wood Buffalo will pay almost entirely on its own, is also more than double the tab for relocating buildings out of floodways across the whole of southern Alberta after devastating floods ravaged the province in 2013.

Fort Mac’s dikes might be the largest Canadian flood-prevention project you’ve never heard of.

The project is also something of an anachronism. “The era of big structural defence developments was really the 1950s and sixties,” says Jason Thistlethwaite, professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Environment, Enterprise and Development. “None of these structures offers absolute protection. So there’s been a real move away from building these defenses and a shift toward what the Dutch are doing: ‘Making room for the river’ " – an approach that includes government-funded buyouts of properties in flood-prone areas, and measures to prohibit new development that would sit in harm’s way.

But retreat is no longer a viable option for Fort Mac. Having allowed development in its floodplain for decades, half of its downtown, often referred to as the Lower Townsite, now lies there. If the city “made room for the river," there wouldn’t be much room left for anything else.

If it seems absurd that a community would knowingly build itself in harm’s way, Fort McMurray’s situation is by no means unique in Canada. Neighborhoods in Fredericton have long existed in the floodplain of the Saint John River. Sainte-Marthe-sur-le-Lac, Que., although inadequately protected by an existing dike, expanded onto an area vulnerable to flooding from the Lake of Two Mountains. And hundreds of homes and small businesses along the Ottawa River, including in the nation’s capital, are dangerously exposed. All those communities experienced severe flooding this spring.

Fort McMurray’s story illuminates how and why communities of perfectly rational people can build directly in harm’s way – and illustrates, as well, the high costs of addressing the mistake of doing so.

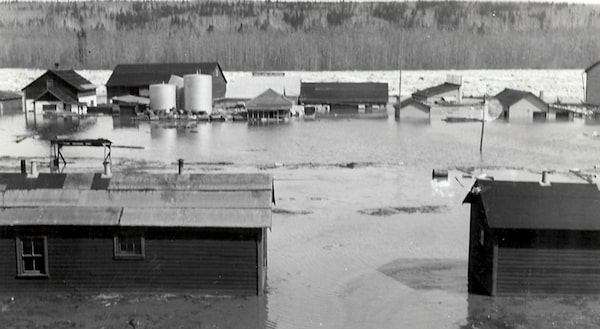

P2007.144.2 Waterways Flood, circa 1932-1936. Credit Fort McMurray Historical Society.Fort McMurray Heritage Society

Fort McMurray’s dilemma has been 150 years in the making.

The city sits near the confluence of the Athabasca and Clearwater rivers, where the Hudson’s Bay Co. set up shop in 1870 to take advantage of these crucial transportation corridors.

But the site was not without its drawbacks. According to municipal documents, Fort McMurray has suffered at least 15 notable floods since 1835 – all but one of them caused by ice jams. As ice along the two waterways breaks up and moves downstream in spring, chunks of it can pile up where the rivers meet. That can cause water levels to rise swiftly, as many as several metres along the Clearwater River, inundating the Lower Townsite.

Over the decades, various options were explored for controlling river ice, including hydroelectric dams, water-storage basins and diversion projects along the Athabasca River. Dikes were contemplated several times, including in the early 1980s, and again around 2000.

Nothing came of any of those plans.

And although some Canadian communities have turned to specialized heavy machinery to manage spring breakup, Wood Buffalo deems such methods ineffective. “We’re really at the mercy of nature,” Mr. Hough says. “There’s no use in explosives or punching holes in the surface [of the ice]. There’s no potential for breaking up the river ourselves.”

(It’s unclear how a warming climate will influence future ice-jam floods in Fort McMurray; academics who have studied this question have found that their severity might actually be reduced. In any case, there are too many variables, and too much uncertainty, to make a reliable forecast.)

But if building on an unprotected floodplain seemed unwise, Fort Mac had few alternatives. The surrounding region features large tracts of muskeg and unstable slopes, leaving little viable land for development.

And so what began as a handful of small log buildings gradually morphed into an assortment of big-box stores, condominium complexes and houses with finished basements. Then, after 2000, things really took off: The city’s population doubled over the subsequent decade. Development in the Lower Townsite intensified even as new subdivisions sprouted on higher ground to the northwest.

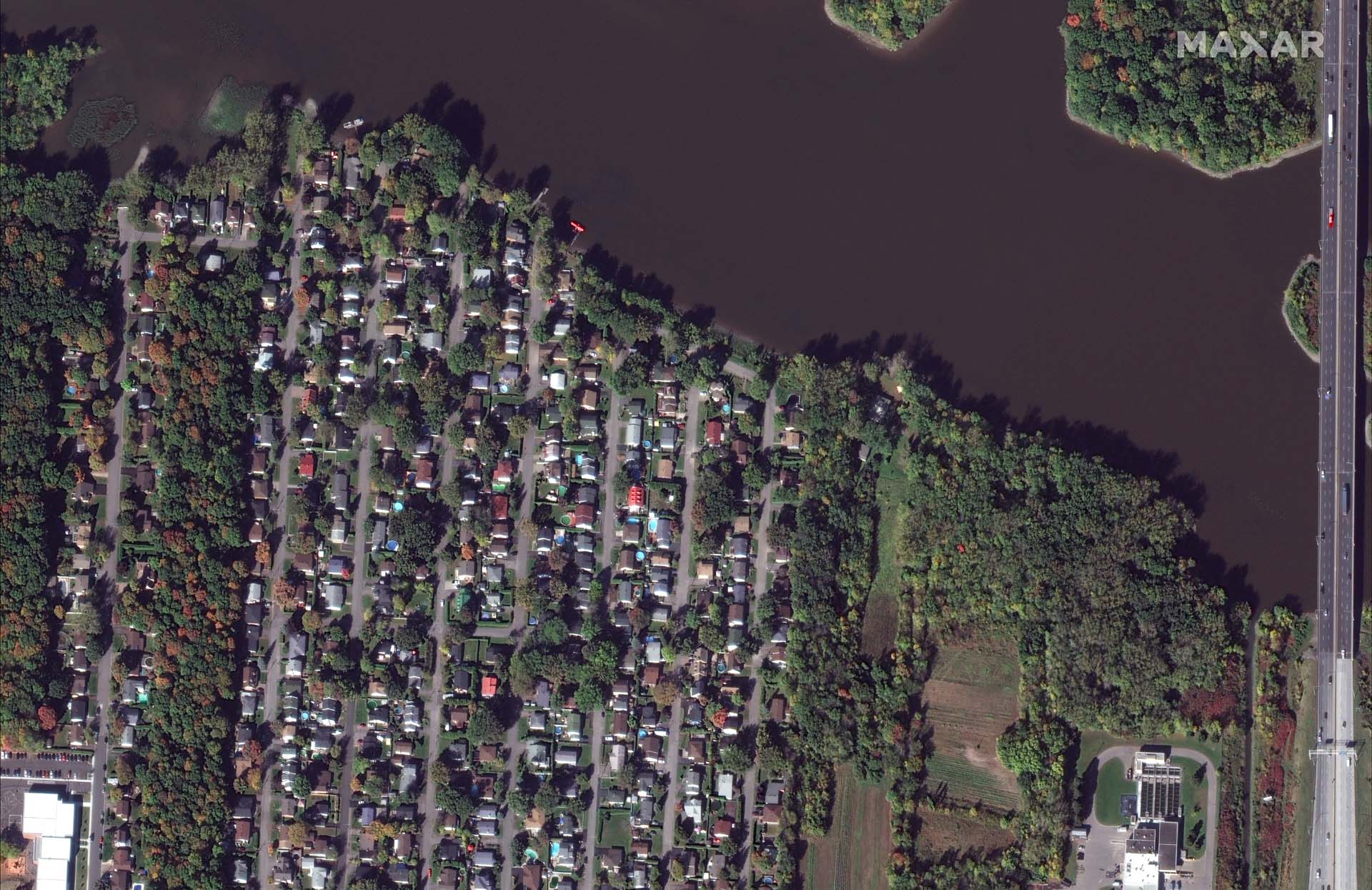

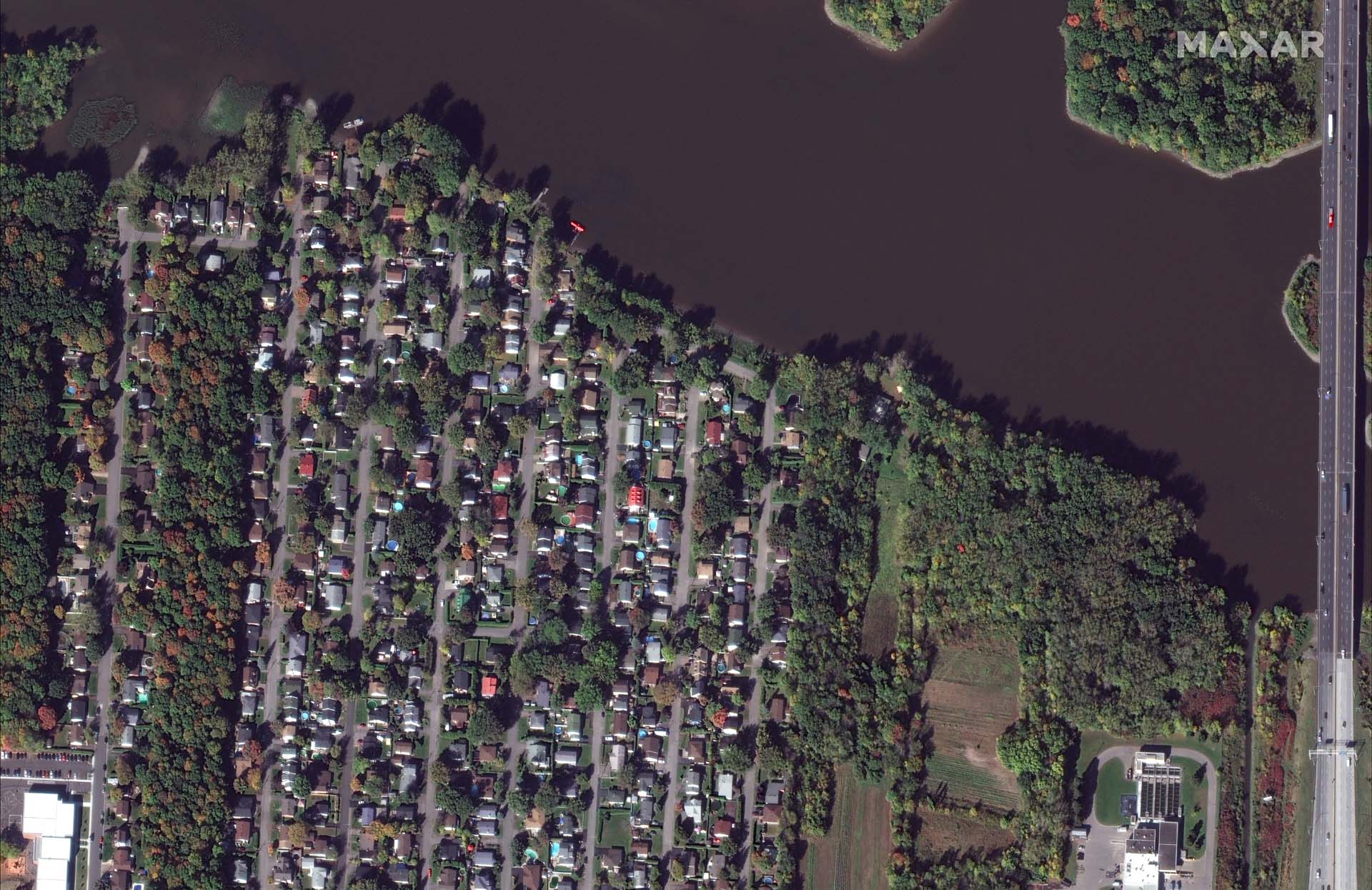

By comparing historical and current satellite imagery, one can see the consequences.

All levels of government knew what was happening.

Back in the 1990s, Alberta joined a federal initiative called the Flood Damage Reduction Program. The underlying bargain: In exchange for federal funding for flood-mapping initiatives, the province would discourage further development in high-risk areas.

As part of that initiative, in 1993, Alberta’s Environment Ministry recommended that 250 metres above sea level be adopted as the design flood level for Fort McMurray – a move that would have effectively halted further development in the Lower Townsite, large parts of which lie below that elevation.

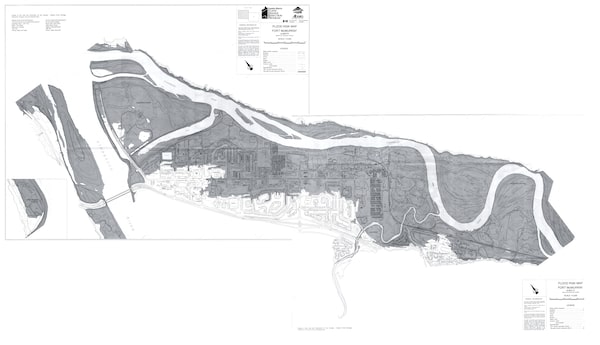

A 1995 flood map of Fort McMurray, created by a joint federal-provincial program intended to halt further development in floodplains.Government of Alberta

But that designation of floodplains as flood-hazard areas never happened.

Merwan Saher, Alberta’s Auditor-General, warned in a March, 2015, report that although Alberta Environment had identified and mapped 48 flood-hazard areas, most – including Fort McMurray – hadn’t been officially designated as off-limits for development. Politics, he said, was to blame. “The lack of designation often reflects a lack of local community support,” Mr. Saher noted, “and the department’s reluctance to impose designation of a community that does not want it.”

By effectively surrendering floodplain regulation to municipalities, Alberta made the same mistake that virtually every Canadian province has made at some time or another, often repeatedly. For local officials, the impulse to allow development in vulnerable areas can be almost irresistible. In the words of one federal document, local authorities “are subject to perverse incentives; they benefit from property development fees and annual property taxes." Meanwhile, it’s the provinces and the feds who get stuck with most of the tab for helping flooded communities recover.

To assess what’s at risk in Fort McMurray, The Globe and Mail acquired high-resolution satellite imagery of the Lower Townsite from 2017 (as well as of the flood-prone Waterways neighborhood immediately to the southeast). We imported that imagery into Picterra, a web-based machine-learning tool that we used to identify buildings (everything from homes, garages and apartment buildings to office and industrial buildings, shopping malls and big-box stores). We then manually added buildings that the tool missed. All told, we identified more than 3,300 structures.

The Globe also acquired data from the provincial government depicting areas expected to go underwater during a 1-in-100 year flood – that is, a flood that has a 1-per-cent chance of occurring in any given year. Using ArcGIS Pro, a geographical-information-system software package, we identified more than 730 structures within the floodplain. We found another 560 structures within the so-called “flood fringe” – where floodwaters would be shallower and slower moving, and thus less threatening.

It appears that approximately 40 per cent of the structures in the Lower Townsite and Waterways are directly in harm’s way.

Several years ago, the municipality began pondering how to revitalize the downtown, increase its population fourfold (to 48,000) and create an arts-and-entertainment hub that would be “the envy of most other large urban centres” across the continent. The municipality wanted more shops, office buildings and homes. Plans grew increasingly ambitious over time, with visions of a $580-million, 6,200-seat sports arena and extensive waterfront development.

The official plan did nod to the city’s history of flooding: It included raising a road along the Clearwater River to double as a dike. But at 248.5 metres above sea level, according to one municipal document, this would provide only “basic flood protection for the 40-year flood level.” (A flood with a 40-year return period has a 64-per-cent probability of occurring in any 40-year period, and an 83-per-cent chance of occurring within 70 years.) In other words, the municipality essentially accepted that occasional catastrophic flooding would remain a fact of living in Fort Mac.

That attitude, however, became untenable after Alberta suffered the worst floods in its history, in June, 2013. The damage in Fort McMurray from the swelling Hangingstone River (one of the city’s smaller rivers, which empties into the Clearwater) amounted to a relatively minor cost of millions of dollars. Heritage Park, a collection of relocated historic buildings showcasing the region’s pre-oil history, turned into a muddy bog. Old wooden floors and foundations suffered extensive damage. The park did not reopen for four years.

This was no ice-jam flood. But those communities in southern Alberta that had similarly allowed unchecked floodplain development suffered recovery costs estimated at more than $5-billion, including more than $200-million in disaster-assistance payments.

That stung.

As often happens after major disasters, politicians vowed to learn from past mistakes. The province committed itself to the principle that it’s easier to keep people away from flooding than it is to keep floodwater away from people. Henceforth, development in high-risk areas would be restricted.

But for Fort McMurray, it was too late to reverse course. Blocking floodplain development there would have meant abandoning the city’s vision for a revitalized Lower Townsite. And Alberta’s emerging regulatory environment granted significant exemptions to certain municipalities, including Fort McMurray, that had “special circumstances.” Don Scott, then the local MLA, told local news media that the province didn’t want to “sterilize” the city’s downtown.

For McMurray’s aversion to retreat was further demonstrated after the cataclysmic 2016 wildfires that destroyed 2,400 homes. More than 200 of those burned in the flood-prone Waterways neighborhood, creating a rare opportunity to remove people from harm’s way. And yet, Wood Buffalo rejected the idea out of hand. “The [municipality] will not be entertaining buyouts from residents within the flood hazard area,” reads one municipal presentation given to Waterways residents in December, 2016. To encourage rebuilding, the municipality even repealed a bylaw that required special flood-proofing measures for newly constructed homes.

Instead, the city committed itself to the principal of keeping the floodwater away from the people: Fort Mac manned the barricades. The municipality hired a consultant to design a series of dikes, elevated roads and retaining walls around the Lower Townsite and Waterways neighbourhoods, to be completed by 2017.

But even that plan was soon interrupted – by falling oil prices. Oil sands companies significantly reduced investment, which rippled throughout the regional economy. Tax revenue began falling well below expectations, a trend that’s expected to continue.

So, Wood Buffalo considered other options. Officials briefly mooted creating a city-backed flood-insurance scheme. Mindful that dikes block views of the river, they also considered demountable transparent walls that would be erected every flood season; that idea was discarded after it became apparent how heavy the walls would have to be to withstand the awesome power of ice jams. And some suggested building to the lower 1-in-40-year standard, a move that would have saved an estimated $60-million in outlays – but that still played chicken with fortune.

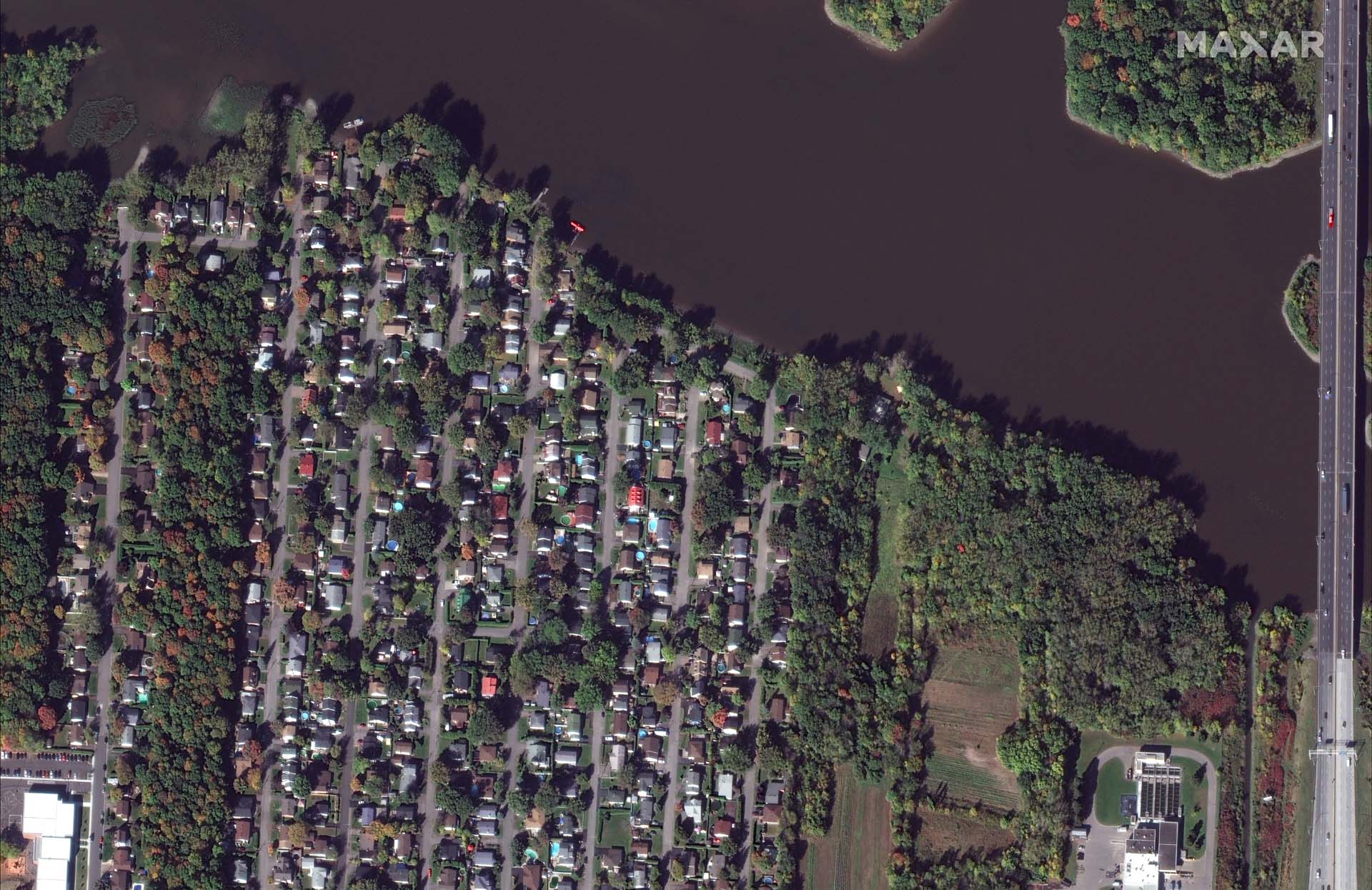

Peak of the flood, west side of Fort McMurray, April 1977. Credit Terry Garvin, FMHS.Terry Garvin/Fort McMurray Heritage Society

Fort McMurray is topping its new defences at 250.5 metres above sea level – slightly above the 1-in-100-year flood level. Even then, it’s taking a gamble. During the worst flood on record, in 1875, rivers peaked at an estimated 252 metres. If floodwaters ever did overtop them, the dikes could make matters worse by trapping water inside the city.

But that disaster has been estimated as a 1-in-350-year event. Karl-Erich Lindenschmidt, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan’s Global Institute for Water Security, who specializes in river ice, thinks Fort Mac is building its dikes to a reasonable elevation. He has modelled ice-jam floods in the community and determined that there’s a limit to how high waters could rise before the force would overwhelm an ice jam and flush it downstream: It’s about 250 metres. “I think that’s a very viable and defendable water level,” he says.

Flood defences on this scale are rare in Canada, but they can work.

Manitoba’s Red River Floodway was completed in 1968 at a cost of $63-million, equivalent to about $450-million in today’s currency. It’s been called one of the largest, most important infrastructure projects in Canada’s history, and multiple studies suggest it has paid for itself many times over. Alberta is now planning new reservoirs on the Elbow and Bow Rivers to protect Calgary, a similarly massive undertaking. Calgary bets it will avoid $10 of flooding damage for every dollar it spends on its own massive infrastructure project.

One certain bet: Fort McMurray will be living with the implications of its decision for generations.

Tim Haney is a sociology professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary who studies how neighborhoods and communities respond to floods and other disasters. He acknowledges that buyouts and zoning restrictions enjoy little political support. But structural defences have their own problems, he says, one being that they encourage developers, municipalities and homeowners to take even greater risks than they did before, because they assume the new berms, dikes and floodwalls will work.

That false sense of security is often compounded, over time, by the fact that flood defences tend to be inadequately maintained – a situation that’s been repeated right across the country.

According to a 2015 analysis by Vancouver-based Ebbwater Consulting, 315,000 people live on the floodplain of the Lower Fraser River in British Columbia. Richmond, Delta and Coquitlam were found to be particularly vulnerable. The dikes protecting many low-lying neighborhoods, the study said, were built decades ago and have been long neglected. Governments must now decide whether to upgrade or replace them, at great expense.

Ontario’s Conservation Authorities operate more than 900 dams, dikes and other structures worth an estimated $2.7-billion. A 2013 report by Conservation Ontario, a non-profit association that represents the authorities, claimed that they received less than half the amount necessary to adequately maintain them. Now, they’ll have to make do with even less: This year, the Progressive Conservative government of Doug Ford slashed their flood-management funding in half.

Protected from the Lake of Two Mountains by a small dike, Sainte-Marthe-sur-le-Lac, Que., expanded over the past few decades from a resort town to a small city of 18,000. This spring, thousands of homes flooded after that dike failed. The mayor promised a taller, stronger dike.

Some argue that Canadians’ faith in engineered solutions has become excessive. “What I’d very much like to see is, around Canada, for us to have a more useful discussion about where that build/no-build line actually is," Prof. Haney says. “Maybe there are certain places we just shouldn’t be letting people live.”

He may get his wish. Few Canadian communities can afford what Fort McMurray is doing – even when higher levels of government offer to help pay. A year ago, the federal government unveiled a $2-billion Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund to support projects costing more than $20-million. And yet, by the time the application period closed on May 31, Infrastructure Canada had approved only $1.2-billion in disbursements, most of that going to large cities such as Calgary, Edmonton and Toronto. Earlier this year, federal officials expressed surprise that they hadn’t received more applications.

Deterred by the costs of large-scale projects, “the lower-tier governments aren’t interested in applying for it,” says University of Waterloo’s Prof. Thistlethwaite. “I think we’re seeing the end of that emphasis on these bigger structural defences."