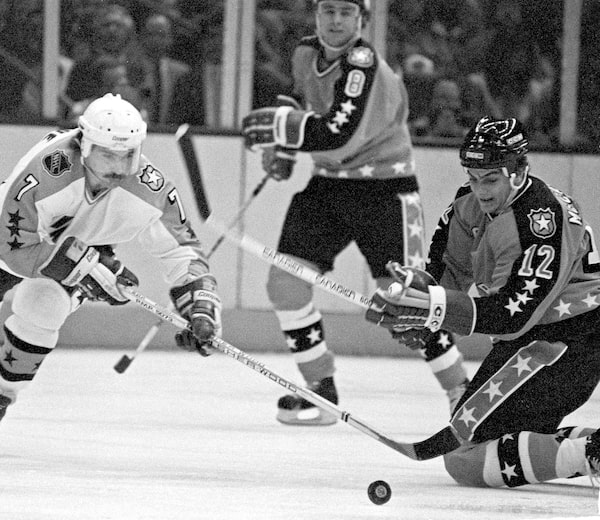

Boston Bruins defenseman Ray Bourque, left, playing for the Wales Conference, and Minnesota North Stars forward Tom McCarthy, playing for the Campbell Conference, go after the puck during NHL All-Star game at the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., on Feb. 9, 1983.Ray Stubblebine/The Associated Press

In 1977, Tom McCarthy pulled off a seemingly improbable coup.

He was drafted before Wayne Gretzky into what’s now known as the Ontario Hockey League, one of Canada’s top junior circuits. While both players entered the pro ranks as teens, Mr. Gretzky wound up in the Hockey Hall of Fame – and Mr. McCarthy landed in prison.

But after his release, the ex-National Hockey Leaguer turned his life around. Mr. McCarthy, who died April 14 of an aortic aneurysm at the age of 61 at a hospital in Chuburna, Mexico, became a highly respected junior coach, helping youngsters avoid mistakes he had made at their age.

“He totally did a 360 [degree turn] from his younger years,” said Steve Black, a long-time friend. “I would describe him as a life coach.”

Thomas Joseph (Tom) McCarthy was born July 31, 1960, in Toronto. He was the second of three children of William (Bill) McCarthy Sr., a home builder, and Joan (née Stewart) McCarthy, a stay-at-home mother. (A few years after Tom joined the Minnesota North Stars, his parents moved to the Twin Cities and, at different times, owned and operated three fish-and-chip restaurants in which their children worked.)

Growing up in Mississauga, Mr. McCarthy emerged as a scoring phenom. Sherry Bassin, the general manager of the Oshawa Generals, picked him No. 1 overall in the OHL draft, knowing that Mr. Gretzky, selected third overall by the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds, was planning to leave for the World Hockey Association after only one season.

Mr. McCarthy enjoyed two outstanding campaigns with the Generals. In 1979, his New York-based agent Art Kaminsky, also a lawyer, threatened to file a right-to-work lawsuit against the NHL in the U.S. if the league did not allow the youngster to enter its draft. The NHL relented and lowered the minimum draft age to 18 from 20.

The North Stars took Mr. McCarthy 10th overall in a first round packed with future hall of famers. After entering the NHL as a 19-year-old, he played hard and partied harder, often missing practices during a nine-season career in which he battled alcohol abuse (which resulted in him going to a California detox centre at one point), injuries, and Bell’s palsy, a temporary condition that causes facial-muscle weakness or paralysis.

However, Mr. McCarthy put up decent offensive numbers, recording 178 goals and 221 assists in 460 regular-season games and another 12 markers and 26 helpers in 68 post-season contests, with Minnesota and Boston. He played in the 1983 NHL all-star game in 1983 and had two chances to win the Stanley Cup – with the North Stars in 1980-81, when the New York Islanders won their second of four straight crowns, and with Boston in 1987-88 season as the Bruins fell to Mr. Gretzky’s Edmonton Oilers.

Following the second finals loss, which ended another season plagued with injuries and Bell’s palsy, Mr. McCarthy became an unrestricted free agent. He failed to stick with the Vancouver Canucks and joined Italian squad Asiago for one season. He then retired and began working more regularly in his family’s first Minnesota restaurant, Just for the Halibut.

Mr. McCarthy told Scott Morrison during a Hockey Night in Canada intermission feature that his legal troubles started when he “stopped dreaming,” became discouraged about the end of his NHL career, and felt like his “life was over.”

In 1994, Mr. McCarthy was implicated in a large FBI drug sting and pleaded guilty to trucking marijuana from California to Minnesota – a felony because the pot crossed state lines. He was sentenced to 10 years in Leavenworth, a notorious maximum-security penitentiary in Kansas.

Bill McCarthy Jr., a Minnesota teacher and former Ottawa Senators scout, said his brother received the stiffest sentence possible because the U.S. government, under 1980s-era President Ronald Reagan, “decided that marijuana was the root of all evil.”

“[The justice] system’s been reformed so that people like Tom [non-violent first-time offenders] don’t get sentences like that any more,” said Jeff Tate, chief of police in Shakopee, Minn.

Mr. McCarthy was Chief Tate’s childhood hero, sparking his interest in hockey, and later changing his “lock ‘em up and throw away the key” attitude toward policing. Young Jeff’s family befriended the McCarthys and lived near Just for Halibut, where he bussed tables at a very young age.

Ironically, the two became pen pals while Mr. McCarthy was in prison and Jeff was training to become a cop. Chief Tate cherishes the letters of advice he received from Mr. McCarthy.

“Seeing him there and getting those letters – and [knowing about] his experiences that he was facing – really changed my perspective and made [me] think about second and third chances,” Chief Tate said.

Tom McCarthy, left, maintained a long friendship with Jeff Tate, now chief of police in Shakopee, Minn.Courtesy of Jeff Tate

At Leavenworth, Mr. McCarthy convinced the warden to allow him to organize a ball hockey league for inmates.

“That’s where I learned I could teach,” Mr. McCarthy told Mr. Morrison during the Hockey Night in Canada segment.

Bill McCarthy Sr.’s relentless negotiating efforts helped Tom get transferred to a Minnesota facility and Ontario’s Kingston Penitentiary before he was released following approximately five years behind bars. Mr. McCarthy reconnected with his friend Mr. Black, a former minor hockey foe, and they began working with a friend’s bantam team in Mississauga, with the ex-con coaching and Mr. Black serving as an on-ice fitness trainer.

Mr. McCarthy went on to coach, and sometimes partly own, small-town junior teams in lesser-known leagues across Ontario, like the Huntsville Otters, Trenton Golden Hawks, North Bay Junior Trappers – who won the 2012-13 Northern Ontario Junior Hockey League title – and Espanola Rivermen/Express. He sandwiched two stints with Espanola around one season (2016-17) coaching a Romanian pro team, before retiring from the game for good.

The Humboldt Broncos’ fatal bus crash in 2018 was a big factor in his decision, Mr. Black said, adding that his friend became wary of riding buses in snowstorms.

Mr. McCarthy married Tina Marchand, a former Huntsville fitness instructor, and they moved to Mexico for the purpose of developing a restaurant. The venture, which involved Mr. Black as well, was stalled by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our dream was always to have a restaurant down in Mexico, and it would have been right on the beach in Progreso [near Chuburna],” Mr. Black said.

In early April, Mr. Black, Mr. McCarthy, and their wives reunited in the region following a two-year, pandemic-induced separation.

“He let us off at the airport and he went to the hospital the next day and never got out,” Mr. Black said. “We had the last two weeks [of his life] with him together, so that was good.”

The NHL Alumni Association, various leagues, and teams have expressed an outpouring of support to the McCarthy family. Bill McCarthy Jr. said he has learned of Tom’s many unheralded acts of kindness from hundreds of letters that he can’t finish reading before crying.

“The challenge that I have with Tom was not how good he was, but it’s how people find the one thing [a drug conviction] that they didn’t care for,” he said.

Tom McCarthy leaves his wife, Tina (née Marchand) McCarthy; her three daughters; his mother; Joan; brother, Bill Jr.; and sister, Patty (née McCarthy) Mallard.