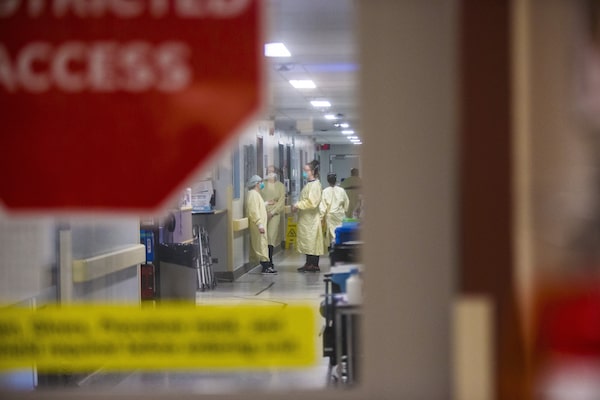

The college is expanding a program called the Practice Eligibility Route, which can take years off the amount of time required for an internationally trained physician to be approved to work in their field.Mikaela MacKenzie/The Canadian Press

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada is making it easier for internationally trained specialists to work in Canadian hospitals as it responds to the country’s doctor shortage, and to complaints that some of its policies discriminate against people with overseas medical degrees.

The college, a certification body that sets national standards for doctors who specialize in fields such as surgery, cardiology and emergency medicine, has been under pressure to streamline the way it assesses foreign-trained physicians and determines their eligibility to write certification exams. Getting these doctors accredited to work in Canada has become a critical issue as the country’s health care system has strained under pronounced staffing problems.

Glen Bandiera, the college’s executive director of standards and assessment, said the certification body is working to remove barriers to licensing for internationally educated doctors by increasing its capacity to review their applications and grant them exam eligibility. Once those changes are complete, he said, the college is planning to provide more flexibility for doctors with foreign training who don’t meet all the Canadian requirements to work in their disciplines. It will do this by allowing them to apply their training to more general disciplines, he said.

The college is also expanding a program called the Practice Eligibility Route, which can take years off the amount of time required for an internationally trained physician to be approved to work in their field. The college, which certifies all specialists in Canada except for family doctors, says this pathway could allow doctors to be cleared to work in as little as two years, instead of seven.

“We want to make it as easy as possible for people who have that competence to demonstrate that competence, regardless of where they trained,” Dr. Bandiera said. “We’re really cognizant of the current health human resources strains in the system.”

A Globe and Mail investigation revealed that Canada is increasingly losing physicians to other developed countries because of shortages of postgraduate residencies for internationally trained medical grads, as well as long delays in assessing their training.

In most provinces, specialist physicians who graduated outside Canada or the U.S. can’t be licensed until they’ve completed five years of practice in their fields, at least the last two of those in Canada. The new alternative path being developed by the college would reduce that five-year requirement to as little as 12 weeks, or up to two years if an applicant requires more time.

Similar practice assessment programs are already used in seven provinces to allow internationally trained specialists in family medicine, psychiatry and internal medicine to enter the work force more quickly – although those programs are limited in capacity and add only about 120 doctors to the country’s medical system each year. Ontario recently announced plans to develop its own assessment program, which it had previously cancelled as a cost-saving measure.

Dr. Bandiera said the college will use that same approach, which puts internationally trained doctors under 12 to 16 weeks of supervision in clinical settings to determine if their training meets Canadian standards, for a range of specialties that don’t have assessment programs in place. This will mean international physicians will spend less time operating under restricted or provisional licences, and it will allow them to help address staffing shortages more quickly, he said.

The certification body told The Globe it will take three to five years to make the Practice Eligibility Pathway available in all 64 specialist disciplines it oversees. The program is now available to about 20 disciplines, and had 250 applicants last year. It is administered by the college, but the expansion will require the co-operation and some funding from provincial health ministries, Dr. Bandiera added.

“The mechanisms already exist. We want to tie them all together in one unified, standardized approach across Canada,” he said. “In some jurisdictions, it would require identification of resources and capacity to do this assessment.”

Clinical assessment programs, while they offer more internationally trained physicians entry into the Canadian system, are not without their detractors. British Columbia recently announced it would triple the number of positions in its on-the-job assessment program to 96 by March, 2024 – but only for people with two years of residency training. Many countries offer only 18 months of residency training to their doctors, with longer periods of clinical training – experience not recognized by the B.C. program.

Rosemary Pawliuk, a lawyer and the president of the Society of Canadians Studying Medicine Abroad, an advocacy group, said internationally trained physicians who want to practise in Canada still face significant barriers. They experience overwhelming discrimination from a system designed to favour graduates of Canadian medical schools and protect the interests of the country’s medical faculties, she said.

The doctors who must cope with those obstacles include thousands of Canadians who have gone to medical schools overseas, she said. They must compete for a separate and much smaller stream of residencies if they want to return home to practise medicine, or spend years longer than domestic grads proving their ability to work as specialists, she said.

Canadian regulators claim all of these barriers are necessary to safeguard Canadians, Ms. Pawliuk said. But she argued that the dangers to Canadians who can’t access health care in a timely manner because of physician shortages are far more serious.

“That narrative of competence is so powerful. But people should be judged based on their individual talents, not where they graduated from,” she said. “That’s why we have to ask: Is this really about protecting the public, or the profession?”