For the first time in six years, Canada is sending one of its own to the International Space Station. And while David Saint-Jacques will be following in some famous footsteps, his time in orbit coincides with the beginning of a new chapter for space exploration, as commercial partners take on new roles and space agencies initiate the next step in humanity’s push toward the final frontier.

A new generation

The Canadian Space Agency astronaut reflects on how growing up dreaming of travelling to space lead him down a career path that made it a reality.

When a guitar-toting Chris Hadfield bumped back to Earth on May, 2013, after a memorable stint commanding the International Space Station, his third and (so far) final trip to space marked the last hurrah for a second generation of Canadian astronauts.

That cohort, which includes Governor-General Julie Payette, was selected by the Canadian Space Agency in 1992 to help build and inhabit the yet-to-be space station.

Not until 2009 did the agency have the need to add new recruits to its human spaceflight program. Now, after a decade of training and anticipation, it’s the turn of David Saint-Jacques to pick up the torch as the agency’s ninth astronaut to reach the launch pad, and the first member of generation three to do so. Together with Ontario’s Jeremy Hansen, he was chosen from a list of more than 5,000 applicants.

Born in Quebec City and raised in Saint-Lambert, outside Montreal, Dr. Saint-Jacques is 48. He and his wife, Veronique Morin, have three young children, two boys and a girl, ages 2 through 7. An avid sailor, cyclist and mountaineer, he holds a commercial pilot’s licence and is fluent in both of Canada’s official languages as well as speaking basic Russian, Japanese and Spanish. Even by astronaut standards, his academic CV is well-rounded enough to pass for a heavenly orb, including a bachelor’s degree in engineering physics, a PhD in astrophysics and a medical degree. Prior to joining the astronaut corp, he was a family doctor in Puvirnituq, an Inuit community on Quebec’s remote Hudson Bay shore, which makes him Canada’s third physician astronaut after Robert Thirsk and David Williams.

Read more: Astronaut David Saint-Jacques kicks off science mission with perception test

Old enough to remember a time before Canada had an astronaut program, Dr. Saint-Jacques has said that he has nevertheless modeled himself after that role since childhood, when he was fascinated with space.

“For me, it started a long process of wanting to understand everything about everything,” he told The Globe and Mail.

Dr. Saint-Jacques was just 14 when Marc Garneau became the first Canadian to fly in space, and he was still an undergraduate when Colonel Hadfield and Ms. Payette were among those picked in Canada’s second astronaut call. Sixteen years later, he was working as a Northern doctor when the next call came up. It was then, Dr. Saint-Jacques said, that he heard a five-year-old’s voice inside saying, “Please try. At least try. You’ve got to give it a shot.”

The journey to orbit

Beyond the drama of launch, it takes hours of preparation and maneuvering to successfully fly from the Earth to the International Space Station. Astronaut David Saint-Jacques has spent months training to prepare for every eventuality.

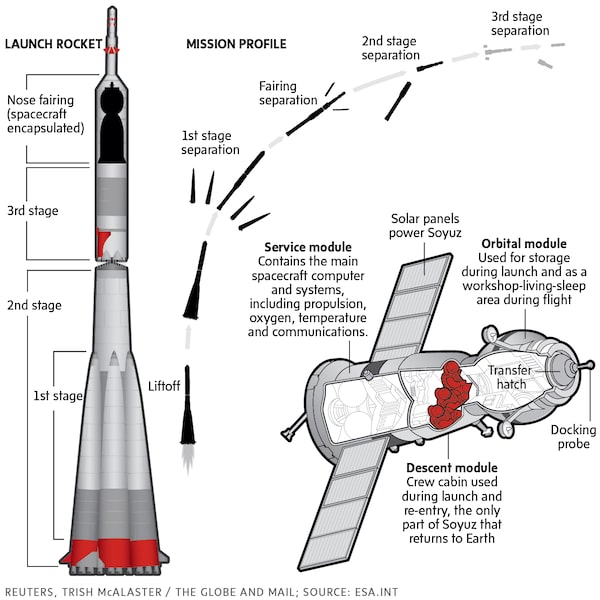

Dr. Saint-Jacques is now under quarantine at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. On Monday, he will board his Soyuz spacecraft in advance of the launch, scheduled for 6:31 a.m. ET. Also on board will be his two crewmates, cosmonaut and commander Oleg Kononenko and U.S. astronaut Anne McClain. The three have trained together for the flight since they were selected for the mission in 2016.

Dr. Saint-Jacques is co-pilot for the launch and six-hour journey to the station. While the journey is brief compared to the six months he is scheduled to spend on the station, preparing for the flight and all the possible emergencies and contingencies that could occur on launch day accounts for approximately half of his training over the past two years.

RUSSIA

KAZAKHSTAN

Baikonur Cosmodrome

UZBEKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

0

650

TURKMENISTAN

KM

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

RUSSIA

KAZAKHSTAN

Baikonur Cosmodrome

UZBEKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

0

650

TURKMENISTAN

KM

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

RUSSIA

KAZAKHSTAN

Baikonur Cosmodrome

UZBEKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

TURKMENISTAN

0

650

TAJIKISTAN

KM

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

This mission will be the first since a faulty sensor caused a Soyuz flight to abort minutes after launch on Oct. 11. While the rocket was destroyed, the crew capsule was able to separate as designed and bring U.S. astronaut Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Alexey Ovchinin back to Earth safely.

Dr. Saint-Jacques witnessed the failed launch and has expressed his confidence in the technology that will carry him aloft on Monday. The accident led to Dr. Saint-Jacques and his crewmates flying nearly three weeks sooner than originally planned, in order to more quickly bring the station’s crew complement back up to six.

While the engineering behind the launch is well-tested, Dr. Saint-Jacques said he was struck by the many rituals and traditions that are part of Russia’s space program. Among them is planting a tree along “cosmonaut alley” at Baikonur, an initiation ceremony for first-time astronauts such as Dr. Saint-Jacques.

His family is on hand for the launch, as is Ms. Payette.

He and his crewmates will enter the capsule about 2½ hours prior to launch. During the final 40 minutes before lift-off, he’ll likely have time to gather his thoughts and listen to music from his own pre-selected playlist, which includes Rêver mieux (Dream Better) by Quebec singer Daniel Bélanger and Radiohead’s Sail to the Moon.

HOW TO PARK A SOYUZ

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometres above the Earth (green). To get to the station the Soyuz capsule first enters an insertion orbit (blue) at an altitude of 220 km. A lower orbit means it is moving faster than the station and can begin to catch up.

Soyuz

ISS

Next, the Soyuz climbs up to a higher orbit (red), about 100 kilometres lower than the station’s, by using a fuel efficient “Hohmann transfer” manoeuvre that requires two engine burns, one at the beginning and one at the end of the manoeuvre.

Once final calculations have been made,

the Soyuz uses a three-burn “bi-elliptic transfer” manoeuvre to match its trajectory with that

of the space station. During final approach,

the Soyuz docks to the station automatically with astronauts ready to take over if there

is a problem.

Note: Graphic is purely schematic.

Drawings are not to scale.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: ESA.INT

HOW TO PARK A SOYUZ

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometres above the Earth (green). To get to the station the Soyuz capsule first enters an insertion orbit (blue) at an altitude of 220 km. A lower orbit means it is moving faster than the station and can begin to catch up.

Soyuz

ISS

Next, the Soyuz climbs up to a higher orbit (red), about 100 kilometres lower than the station’s, by using a fuel efficient “Hohmann transfer” manoeuvre that requires two engine burns, one at the beginning and one at the end of the manoeuvre.

Once final calculations have been made, the Soyuz uses

a three-burn “bi-elliptic transfer” manoeuvre to match its trajectory with that of the space station. During final approach, the Soyuz docks to the station automatically with astronauts ready to take over if there is a problem.

Note: Graphic is purely schematic.

Drawings are not to scale.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: ESA.INT

HOW TO PARK A SOYUZ

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometres above the Earth (green). To get to the station the Soyuz capsule first enters an insertion orbit (blue) at an altitude of 220 km. A lower orbit means it is moving faster than the station and can begin to catch up.

Next, the Soyuz climbs up

to a higher orbit (red), about 100 kilometres lower than the station’s, by using a fuel efficient “Hohmann

transfer” manoeuvre that requires two engine burns, one at the beginning and one at the end of the

manoeuvre.

Once final calculations have been made, the Soyuz uses a three-burn “bi-elliptic transfer” manoeuvre to match its trajectory with that of the space station. During final approach, the Soyuz docks to the station automatically with

astronauts ready to take over if there is a problem.

Soyuz

ISS

Note: Graphic is purely schematic. Drawings are not to scale.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL; SOURCE: ESA.INT

THE INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION

After braking to slow down

and match the speed of the ISS,

the Soyuz connects to one

of the station’s Earth-facing

docking ports.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

THE INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION

After braking to slow down

and match the speed of the ISS,

the Soyuz connects to one of the

station’s Earth-facing docking ports.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

THE INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION

After braking to slow down

and match the speed of the ISS,

the Soyuz connects to one of the

station’s Earth-facing docking ports.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Aboard the space station

David Saint-Jacques explains how a modern country like Canada can’t function without satellites and spaceborne sensors supporting communications and industry.

It’s been more than 20 years since the first component of the ISS was launched into orbit and has been continuously occupied since November, 2000. In that time, the approximately US$150-billion station has grown to 100 metres in its longest dimension and gradually come into its own as an orbiting laboratory.

For astronauts, it has proved to be a busy place, partly to keep the station in working order in addition to the experiments that astronauts are engaged in as part of their day-to-day work.

During his six-month stint, Dr. Saint-Jacques will have ample opportunity to work with the Canadarm II, which has become increasingly indispensable during docking procedures with supply ships and for maintenance. At some point, he may also be required to don a spacesuit and go outside the station, though it’s not known if this will be necessary. Like others aboard the station, his training has included hours of practice with the Canadarm in simulators on Earth and rehearsing for space walks.

During a final briefing with reporters on Thursday, Dr. Saint-Jacques said one of his biggest fears about his mission is that he will become so focused on all the tasks that he’s there to perform that he will forget to pause often enough to take in the full experience.

For that reason, he said, he plans to carve out time during his six-month stay for a 1½-hour continuous viewing of the Earth – the amount of time it takes for the station to trace a full circle around the planet.

Science in space

Astronaut David Saint-Jacques talks about the importance of telemedicine in space, and how it can be used in remote situations on Earth.

As a former physician in a remote part of Northern Quebec, Dr. Saint-Jacques has repeatedly said that some of the technologies and experiments he is most interested in working with are those that could pave the way for telemedicine in space. While astronauts on board the station are typically only a matter of hours from Earth if a serious medical issue should arise, having the ability to deal with medical care in space will become a necessity during any effort to take humans beyond the Earth-hugging orbit where the space station resides.

The CSA sees telemedicine as a promising avenue for its future involvement in human spaceflight, in part because technologies and protocols developed for deep space missions could also be put to use in communities across the North.

Dr. Saint-Jacques will also be working on several new and continuing experiments that are part of Canada’s science effort on the station. As early as next week, for example, he is set to become subject number one in an experiment designed by Laurence Harris at York University in Toronto.

For the experiment, he will strap himself into a harness and don a pair of virtual-reality goggles, which will present him with a series of visual effects designed to test how he perceives his orientation and motion while in space. This is comparable to what subjects who have vestibular issues – problems with the inner ear and sense of balance – would experience on Earth.

Among the medical experiments that Dr. Saint-Jacques will participate in is a study led by Guy Trudel at The Ottawa Hospital, which tracks changes to astronauts’ bone marrow during spaceflight and explores whether those changes can be reversed. He will also be part of a psychology study, which began in 2015 by researchers at the University of British Columbia that is exploring how astronauts cope with feelings of separation from family and with stress during long-duration space missions.

To the moon and beyond?

The next step in space exploration may be the Lunar Gateway, which will orbit the Moon rather than the Earth, as the aging International Space Station does now. Globe Science Reporter Ivan Semeniuk outlines the important choice Canada needs to make to participate in the Gateway or be shut out by other international partners.

Since the last space shuttle flew in 2011, Soyuz has been the only option for astronauts heading to the space station. That’s set to change next year with SpaceX and Boeing both aiming to make history by staging their first crewed test flights to the station.

That means the next Canadian to fly in space – expected to be airforce pilot Jeremy Hansen in a few years’ time – is more likely to ride up to the station in a commercial U.S. vehicle rather than in a Russian capsule.

U.S. President Donald Trump has said he wants to privatize the space station by 2025. It’s not clear how that would work for NASA’s international partners who have their own stake in the orbiting laboratory. While commercial presence on the station may increase, there are plenty of policymakers in the United States who would like to see NASA’s commitment extend beyond 2024, including in Republican-red Texas, where the station’s mission control and the U.S. astronaut program are based.

Canada’s presence on the station is a function of how much it chips in for the facility – a share that has decreased over the years relative to other partners. Last year, the CSA introduced its two newest astronauts, Joshua Kutryk and Jennifer Sidey, who have now begun their training. At Canada’s current level of commitment, they would potentially see their first mission opportunities in the late 2020’s.

Long before then, Canada will need to decide if it wants to join with the United States and other space-station partners to develop a more distant outpost around the moon called the Lunar Gateway.

Two weeks ago, NASA chief administrator Jim Bridenstine was in Ottawa strongly encouraging Canada’s involvement, potentially by supplying robotics and other technologies to the project. In exchange, a future voyage by a Canadian astronaut may include the moon as its backdrop.

The Trudeau government has so far not embraced the idea, instead pushing off a long-awaited strategy for Canada’s space program till next late year.

Meanwhile, the more distant goal of sending humans to Mars remains on the horizon, a goal that Mr. Bridenstine underscored while congratulating the team that successfully landed NASA’s Mars InSight probe on Monday. In doing so, he portrayed the Lunar Gateway as a necessary middle step for developing the capability to safely conduct human exploration on Mars later this century.

As David Saint-Jacques ascends to the space station next week, the child that could grow up to become the first Canadian on Mars may well be watching.

Watch how David Saint-Jacques spent 10 years training for his space mission

Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques spent almost a decade training for his mission to the International Space Station. Watch as he is put through his paces preparing for his role as Canada'a next astronaut in orbit.